In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic 1925 novel The Great Gatsby, Daisy Fay is a mercurial character. The popular rich girl from Louisiana — married to Tom Buchanan, an adulterous brute — is ravishing and entrancing and, at times, cruel. It is her voice that most draws Jay Gatsby to her years after their initial fling when he was a poor officer, as he longs for her across the bay.

As Fitzgerald describes it, Daisy’s is a voice that rises in dramatic swells and falls to intimate murmurs, coaxing its listeners to draw closer. Gatsby, the nouveau-riche rumored bootlegger from an impoverished farming family, is obsessed with Daisy: her class, her beauty, her unattainability, her voice. It is a voice, he tells the book’s narrator Nick Carraway, that is “full of money.”

Imitating that voice is no easy task; double that pressure in a musical where Daisy must show off her capricious charms singing as well as talking. Thankfully, in Chunsoo Shin’s dazzling new Broadway production, Eva Noblezada (Miss Saigon, Hadestown) rises to the occasion. And then some.

Noblezada’s Daisy — a character who is often miscast, woefully so in the 1974 and 2013 film versions of the novel — has a gorgeous singsong richness to her speaking voice, at once girlish and imperious, flirtatious and husky and sparkling. This is Daisy as she is meant to be: rich and spoilt and radiant and sad and full of yearning.

The Great Gatsby fell under public domain in 2021, leading to a spate of adaptations (a second musical, Gatsby, with music by Florence Welch of Florence and the Machine, premiered in June at the American Repertory Theater). In this version, composer Jason Howland and lyricist Nathan Tysen have jumped headfirst into the romance and tragedy of the novel in a memorable score that swells with emotion.

There is also plenty of texture: songs such as “The Met” and “Only Tea” are clever, irreverent and witty, with laugh-out-loud moments. They provide relief to a story that, in the second act, becomes nearly unbearable with suffering and calamity. (The lyrics don’t try to imitate the incomparable Fitzgerald, but tap effortlessly into the modern day. “If I wondered whether Tom’s an asshole,” sings Nick, “Tom’s an asshole.”)

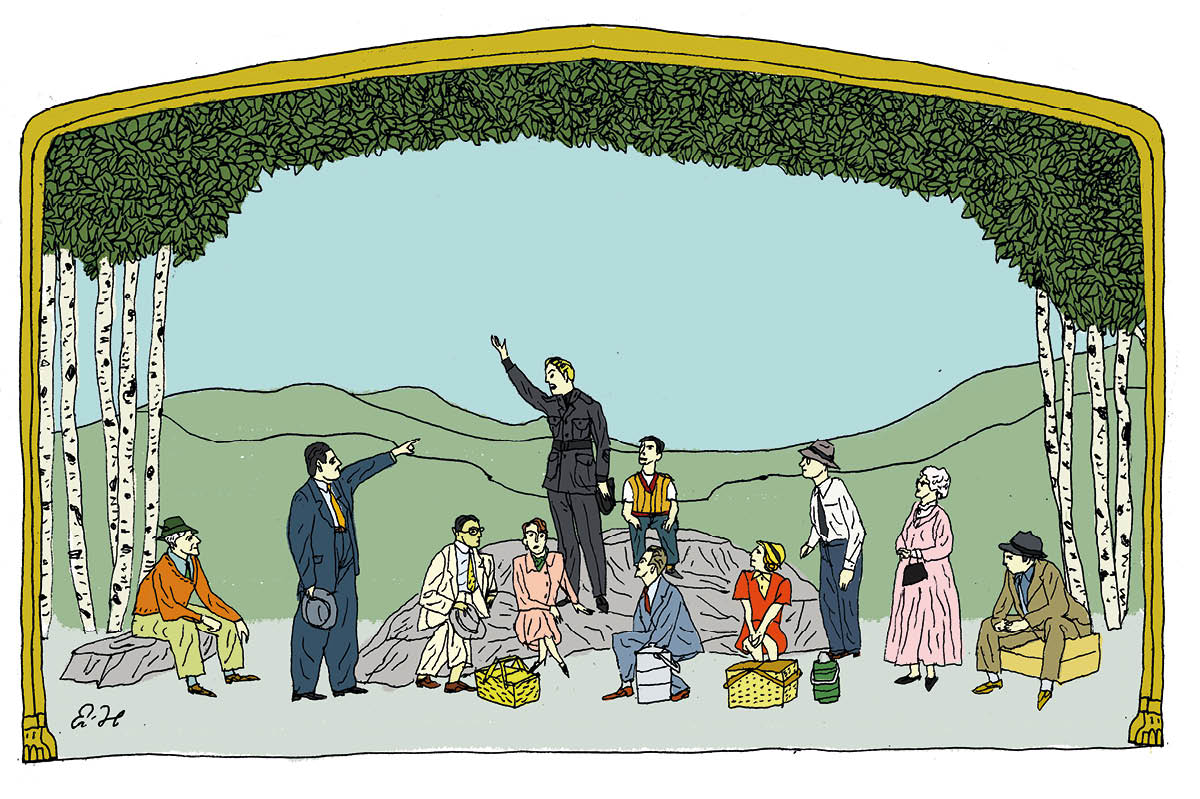

Where The Great Gatsby falters are in its ensemble moments, whose riffs take inspiration from the 1920s. Choreographer Dominique Kelley and costume designer Linda Cho (who is restrained when dressing Daisy and her golfer lady friend Jordan Baker, going for elegance) veer towards Vegas garishness in the saturated and glam party scenes. Gatsby’s parties, of course, are meant to be lurid and racy, but this feels like overly camp dressing-up, rather than true to the more risqué roots of the book. It’s hammy.

Thankfully, the main cast’s nuanced performances, superbly directed by Marc Bruni, make up for those initial embarrassing ensemble scenes. Broadway star Jeremy Jordan is handsome and debonair as Gatsby, littering his speech with the requisite “old sport” and bringing both heartfelt bigness and tenderness to his songs. He has the megawatt smile that is so important, but also the beefy build and grit that hint at a less than savory past.

Jordan is also funny: when he asks Nick to invite Daisy to tea, then loses his nerve, he is adroit at the physical comedy, showing the more absurd and anxious side of “James Gatz,” a man, after all, whose whole existence as the smooth-talking millionaire “Gatsby” is a performance.

Noah J. Ricketts is affable and appealing as Nick, providing a moral compass that, while muddied in the book, is streamlined to guide the audience in a musical of this scale. His love interest Jordan Baker is played by Samantha Pauly with athletic poise and sass, while Sara Chase is crass and shrilly sensual as the doomed lower-class Myrtle Wilson and John Zdrojeski is lankily imposing as the nasty and domineering snob Tom.

Much of the applause must go to the book’s writer Kait Kerrigan, who has stayed true to the essence of the source material while simplifying the story for the stage production. While the general plot remains the same, Kerrigan has dropped Gatsby’s backstory, presumably for the sake of manageability (we can assume that most people visiting the musical will have some familiarity with the book). She has also amped up the romance between Nick and Jordan, who in the novel are aloof and cool with each other, but here are deeply involved.

They are used as foils to Tom and Daisy, trapped in their gilded cage, unable or unwilling to admit that the world is changing. By contrast, Jordan is a new type of girl, who fights for her independence and questions the institution of marriage, fearful that in the end all it spells is disappointment. It’s a sober take in a musical that goes big on romance and thwarted love, before crashing all those fantasies into the water, showing them to be illusions.

Indeed, much of The Great Gatsby is big. Paul Tate dePoo III’s Art Deco inspired set and projections dazzle. The songs explode. The passion overwhelms. It’s opulent when it needs to be, fun when it needs to be, and intoxicating, much like the story Gatsby spins in his own life.

So, it’s all the more shocking when everything comes crashing down: when Daisy reveals herself to be selfish and ruthless (spelled out here in a final confrontation with Nick that doesn’t happen in the book) and when Gatsby’s desires for wealth and class ascent turn out to be as hollow as we know they will.

I won’t spoil exactly how he meets his end at his pool. All I’ll say is, it’s a brilliant piece of theater and a fitting climax for a story about gross excess, love soured and dreams dashed.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply