To grasp the untamed vastness of Samburu County, it’s necessary to get high. Above the thickets of acacia trees, thorny branches like barbed wire against the cloudless sky. Out of the Rift Valley’s rubbly trenches, dotted with bleached animal skulls and groves of candelabra-like doum palms clustered around some-time watering holes. To the peak of Sundowner Rock, for instance. After scrambling up its boulder-strewn slopes — wishing for the agility of the bug-eyed, Bambi-like dik-diks that prance about this terrain — I flop down on a sun-warmed granite slab and savor an eagle’s eye view of the bushland below.

Legions of acacias and wiry shrubs mottle the red earth. Not a single building or human stands between me and the distant horizon, but volcanic forces have sculpted all manner of rock formations: neat pyramids and looming ridges, the distinctive knuckle-shaped summit of Mount Kenya, outcrops resembling the wizened faces of tribal elders. The Ewaso Nyiro river is a ribbon of scarlet mud, thirsting for seasonal rains. These highlands are the gateway to the Northern Frontier District — “Kenya’s last really wild place,” as Riccardo Tosi, the Safari Collection’s chief development officer, puts it.

What sets Samburu apart from the country’s better-known, southerly safari parks isn’t only its varied, craggy landscape and semi-arid climate, but the wildlife specially adapted to live in it. Heading into Samburu National Reserve on a game drive the following morning, my eyes are peeled for the “special five,” a group of herbivores not found anywhere else in Kenya. First up: a gerenuk. Picture an antelope whose ears and throat have been stretched out like silly putty. This evolutionary feature, along with the ability to walk on its hind legs, helps the creature reach more succulent high-growing leaves.

Speaking of elongated necks, a pair of reticulated giraffes are thwacking theirs against each other’s flanks — young bucks fighting for dominance. Their blows make dull thuds that carry across the still, hot air. Brutal headbutting notwithstanding, the polygon-shaped patterning of this species’ hide is more beautiful, I think, than the irregular splotches seen on its relatives. Likewise, Grevy’s zebra — larger and rarer than the Plains variety — possesses stripes with a particularly calligraphic flourish, thick strokes tapering to a pure white belly. A lone Beisa oryx, whose ruler-straight horns are almost as long as his silvery-gray body, takes our Special Five count to four. Only the Somali ostrich evades us.

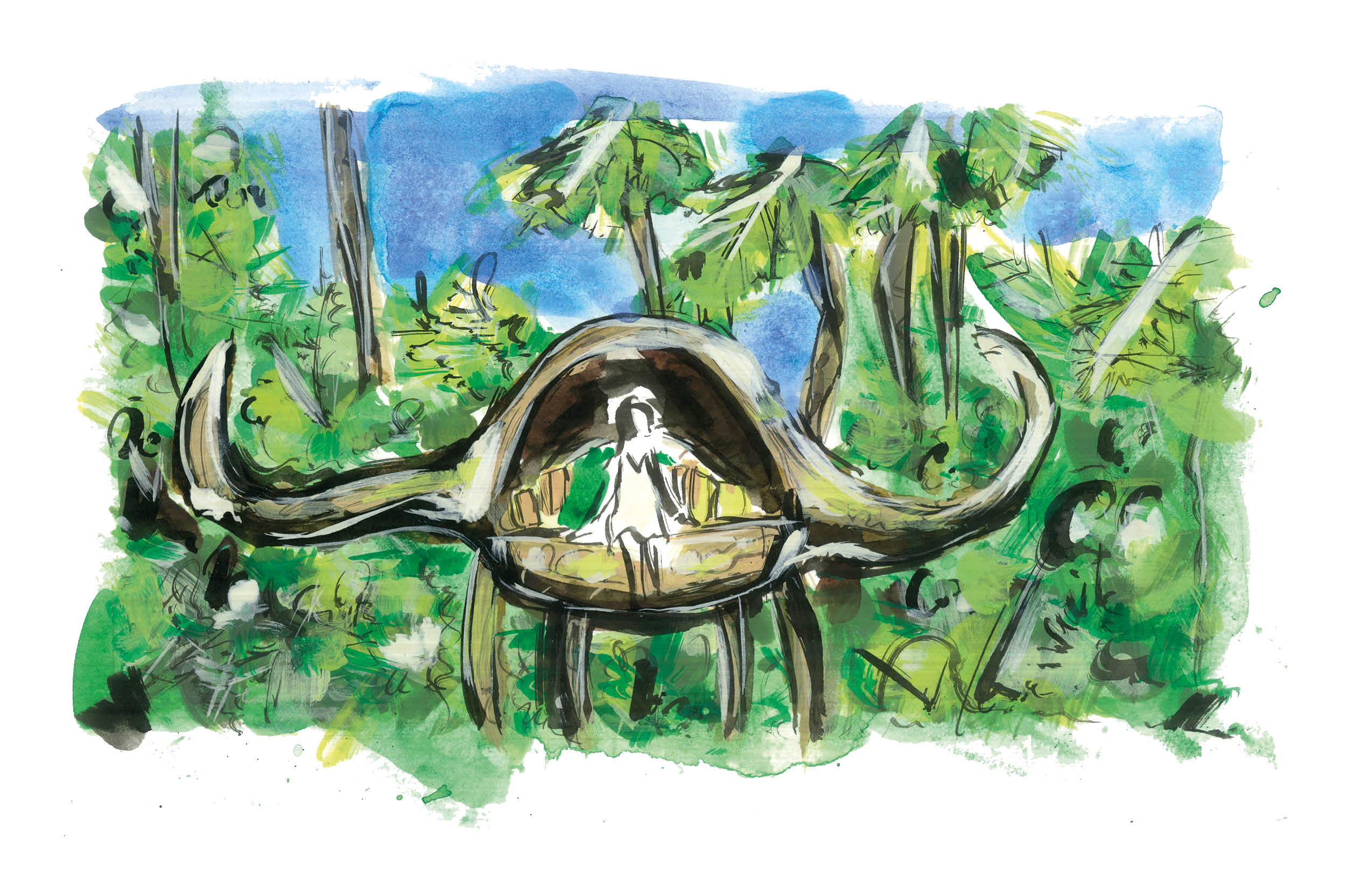

Given how off-the-beaten-track Samburu is, camps are few and far between here, but Sasaab leads the way in sustainable luxury lodgings. Named after a white-blossoming local shrub, its nine “tents” (if such a humble name can really be assigned to these palatial, thatched dwellings complete with four-poster beds, rainfall showers and private plunge pools) range over a rocky ridgeline. Set within a community-run conservancy, rather than a national park, Sasaab doesn’t restrict its guests to safari vehicles; they can instead join Samburu tribesmen on bushwalks, as we did to Sundowner Rock, or on a camel ride along the dried-out riverbed, where elephants were burrowing their trunks into the cracked mud, sipping up subterranean reserves of water.

It’s all changed when our twelve-seater plane touches down on the Maasai Mara’s Keekorok Airstrip. A sea of rippling golden grass greets us. No tree thickets here, only the occasional desert date standing solitary on the low horizon. “About 80 percent of the Mara is open grassland,” explains Moses Kaleku, a guide at Sala’s Camp, as he plows the Land Rover through six feet of the stuff. “Right now, it’s very tall, but when the Great Migration has finished, it’ll be down to just an inch. The herd really cleans up,” he chuckles.

Across these gently rolling plains, grazing buffalo are silhouetted like countless black boulders, visible from miles away. One hand on the steering wheel, Kaleku points out a motley crew of gazelles, topis and zebras. “It’s called the dilution effect — multispecies groups coming together. They know there’s safety in numbers.” Sure enough, shadows are slinking through the long grass. Lolling gaits and eerie whooping calls carry on the warm breeze; a clan of spotted hyenas is trailing the herd. One approaches our Land Rover and raises its snout, sniffing us out. Kaleku insists they’re more interested in picking off buffalo calves than tourists, though.

Lions love to lounge beneath orange-leaf croton bushes — the leaves contain a natural insect repellent — and sure enough this is where we find our first pride, ripping into a warthog carcass. The six cubs are scarcely bigger than housecats, frequently breaking away from dinner to swat a sibling’s tail or cuff an ear, yet there’s a disconcerting sound of cracking bones as they eat. And when the male turns his magnificent, battle-scarred face toward us, I’m suddenly all too aware of the blood pulsing hard in my own throat.

If safari in Samburu felt like a treasure hunt, uncovering quirky species in varied terrain, then in the Mara it’s all about the abundance of wildlife. Those vast herbivore herds and the big cats they attract. Even back in Sala’s Camp — a peaceful, canvas-clad oasis kitted out with antique steamer trunks, beaded Mara artwork and copper bathtubs — dozens of hippo wallow in the creek that winds through the site. Whenever we cross the bridge, a Nile crocodile slides through the dark water to position himself underneath ominously and opportunistically.

“Kenya’s smaller than Tanzania or South Africa, but the diversity is unbeatable — the diversity of landscapes, the wildlife and the people,” Tosi reflects. “An hour’s flight from Nairobi can get you to sand-dune desert or a place that looks like Scotland [the misty highlands of Laikipia], to the classic Out of Africa savannah or the rugged terrain around Sasaab that reminds some visitors of Utah or Arizona.”

His comments take me back to Sundowner Rock, when safari guide Michael Laur handed over a gin and tonic garnished with wild mint (happily, there seems nowhere too remote for a cocktail to be conjured up on safari) and shrugged, “The Mara? It’s a different country down there.” This, I’ve come to see, is exactly what makes a multistop Kenyan safari so compelling. Two wildernesses that are even more splendid not in isolation, but as a duet.

The joys of Giraffe Manor

Many safari-goers landing in Nairobi hop straight on to domestic transfer to far-flung reserves — but they’re missing a trick. A night in the leafy suburban grounds of Giraffe Manor lets you acclimatize after an international flight, or as I did, eke out your safari adventures and prepare to return to “normality.” Not that everything in this historic hotel is exactly normal. Rothschild’s giraffes from the neighboring conservation center amble up the lawn twice daily to join guests for breakfast and afternoon tea (grass pellets for them; scones and finger sandwiches for you). Heads with long lashes and slurping tongues swoop through the mullioned windows; some visitors even choose to kiss the charismatic long-necked visitors.

You’ve got to salute the Manor’s commitment to the theme, too: everything from doorstops to chess pieces to pewter water jugs are giraffe-shaped. Just across the gardens, meanwhile, The Retreat makes light work of awkward layovers by offering spacious day rooms (complete with giraffe-patterned eye masks), a swimming pool, healthful café and jet-lag-busting massages.

Estella Shardlow was a guest of bespoke Africa and Latin America specialist Rainbow Tours, which offers a five-night itinerary in Kenya with two nights at Sasaab, two nights at Sala’s Camp and one night at Giraffe Manor from £5,990 or $7,510 per person sharing. For more information contact +44 203 773 7945 or rainbowtours.co.uk. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply