CrowdStrike. What a name. It sounds, doesn’t it, like exactly what it’s meant to prevent? And a cloudstrike, in the sense of a bolt from the blue, is exactly what the company produced: millions and millions of Windows PCs simultaneously succumbed to the Blue Screen of Death, as a company whose whole raison d’etre is averting internet catastrophe caused one. The biggest, supposedly, in history.

Is it in bad taste to say that the great internet outage of July 2024 was, in some respects, just a little bit funny? Plainly, it wasn’t funny if you were trying to book a doctor’s appointment, or trying to pass through an international airport, or had a lot of money in, say, CrowdStrike shares. But there was undeniably a sort of festival atmosphere amid all the chaos. For tech-support workers, of course, it was a complete nightmare; but for everyone else it was a bit like a snow day at school. Television anchors milled about the TV studios that couldn’t go on air; traders stopped shoveling money about the world and sat wanly at their desks in the blue glow of their dead monitors.

We rely on the internet in much the same way as our forebears would have relied on their deities.

There were unexpected and ironic winners and losers. Up, for instance, was America’s Southwestern Airlines, which survived the disaster by virtue of running its whole system on a version of Windows so old that its obsolescence provided a form of protection in itself. Smug, too, were the Russians, who don’t use Windows because the sanctions regime has forced them to de-Microsoft themselves already.

And all because of one little mis-programmed update that quietly downloaded itself to millions and millions of computers and borked them in a way that’s going to take weeks to fix. I don’t know if this would count as a “single point of failure” — being after all a single thing that failed everywhere at once. Reminded me a little of that Damon Runyon story in which Big Jule, holed up in a barn, describes using rats for target practice: “sometimes when you hit a rat with a forty-five up close it is not always possible to tell afterwards just where you hit him, because you seem to hit him all over.”

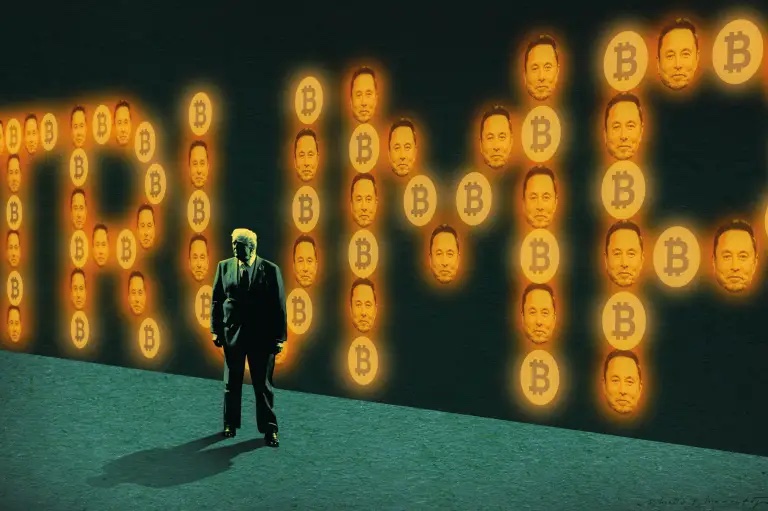

It was a salutary moment, as well as a tragicomic one. It’s a reminder, after all, that for all our technical advances, for all the vast complex architecture of the modern world, we’re never more than a fat finger error away from a global pratfall. The internet looks shiny and exciting, but it’s held together with chewing gum and bits of string. Here’s a lesson in the vanity of human wishes. Also, perhaps, in the dangers of the sort of vast tech monopolies that allow a few bum lines of code to knock out 8.5 million computers all around the world at a stroke.

And how are we to apportion blame? CrowdStrike’s share price has cratered, which seems to be fair enough. But the total cost of the outage is estimated to top one billion dollars. We can expect a few lawsuits, but the idea that anybody, let alone everybody, is going to be able to recover their losses is surely for the birds. And the funny thing? Technical experts who’ve been interviewed said that it’s highly unlikely, even after last week’s catastrophe, that more than a handful of CrowdStrike’s customers will desert it. It’s too big a player and its software is too deeply embedded in their systems to be easily swapped out. Already airlines are treating this as something like an act of God, with the Civil Aviation Authority suggesting that it will fall under the “extraordinary circumstances” get-out which prevents airlines having to pay compensation for canceled flights.

It is, in a way, an act of God. We rely on the internet (and now, increasingly, on the baroque and opaque algorithms of artificial intelligence) in much the same way as our forebears would have relied on their deities. Our relationship with the internet saturates every aspect of our lives, and most of us (myself very much included) have only the very sketchiest idea of how any of it works. We rely on a priesthood of techies who, themselves, have less and less idea of how it works. As with the old-time Gods, fear and trembling is appropriate.

A netquake like this, then, is the twenty-first century’s informational equivalent of an earthquake or a flash-flood. It’s more like a natural disaster than an ordinary human error. And no matter how much we may seek to improve the resilience of our systems, everything is so profoundly interconnected in the digital world that, one way or another, we’ll always be vulnerable to that sort of snafu propagating through these fragile, jerry-built systems at the speed of an electron. So much for our illusions of control.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply