American politics seem particularly febrile in 2024. The sitting president has withdrawn from the election, days after his predecessor was shot campaigning at a rally in Pennsylvania.

But American democracy is by nature restless and tumultuous. It’s worth remembering that fifty years ago this week, Washington was in turmoil over the question of whether Richard Nixon was going to resign.

Those early days of August 1974 seem like yesterday to those of us who became swept up in them. At the time I was a thirty-one-year-old member of parliament in the UK, five months into my first parliamentary term as an opposition backbencher. My summer recess took me to the home of a hospitable Anglophile hostess in Georgetown. In her basement lived two presidential aides who helped to give me a ringside seat to the resignation melodrama. At its peak I was invited by them to lunch in the White House Mess, where the press secretary, Ron Ziegler, persuaded me to write a letter to the soon-to-depart president. This correspondence started a relationship which eventually led to me becoming Nixon’s biographer.

My lunch in the White House Mess took place in the days before the president resigned

The countdown to the president’s resignation began on July 16, 1973, during the Watergate hearings of the House Judiciary Committee (“the greatest show on Earth,” according to the historian Theodore H. White) when a staffer, Alexander Butterfield, unexpectedly disclosed that Nixon’s Oval Office contained a voice-activated taping system. This caused a sensation. “NIXON BUGS HIMSELF,” screamed the headlines. They triggered a legal battle which ended with a unanimous Supreme Court ruling that the tapes were not covered by executive privilege and must be handed over to the judiciary committee.

One of the subpoenaed tapes recorded on June 23, 1972 became known as the “smoking gun.” It showed that Nixon had discussed ordering the CIA to block the FBI’s investigation into the Watergate break-in. This attempted cover-up seemed to prove that he could be found guilty of obstructing justice if he were impeached for this criminal offense in a trial before the Senate.

At the beginning of August 1974, only a small group of insiders were aware that the smoking gun tape was a bomb waiting to explode. Nixon himself knew it. He tried desperately to find escape routes that might save his presidency, reaching out to friendly Republican and southern Democrat senators who might vote against his impeachment. These overtures failed.

In his hours of pre-resignation agony, Nixon the realist was sometimes supplanted by Nixon the fantasist. His daughters begged him not to throw in the towel (just as, reportedly, Joe Biden’s son Hunter and wife Jill did in the first days of last month). For a while, Nixon seemed to be swayed by their pleas: “End career as a fighter,” he scribbled defiantly on his notepad one sleepless night.

My lunch in the White House Mess took place shortly before the fighting president became the resigning president. My hosts were Frank Gannon Jnr and Diane Sawyer — who was later to become a presenter for CBS. In August 1974 they were junior staffers working in the office headed by Ziegler.

“Sorry, it’s like a morgue in here right now,” said Frank, as we ate our Caesar salads in an almost empty dining-room. Ziegler had joined us at our table. As one of Nixon’s closest confidants, he should have known what was going to happen, but evidently he did not, and he asked me a surprising question: “If the president were to resign, what do you think his future would be in the eyes of the world?”

Hesitatingly, I replied: “I believe the day will come when Mr. Nixon will again speak out on foreign policy issues and be listened to, with respect, by audiences across the world.”

“How profound!” said Ziegler.

After lunch he drew me aside: “That profound reflection of yours,” he said. “Would you mind writing it down? I would like to give it to the president.”

I was vain enough in those days to travel with my newly minted parliamentary notepaper. So I wrote a short letter of sympathy to President Nixon containing the thought I had just expressed.

Outside the White House, hatred rather than sympathy for the thirty-seventh president prevailed as the crowds kept chanting: “Jail to the chief!” Inside the Oval Office, it was becoming clear that the game was up.

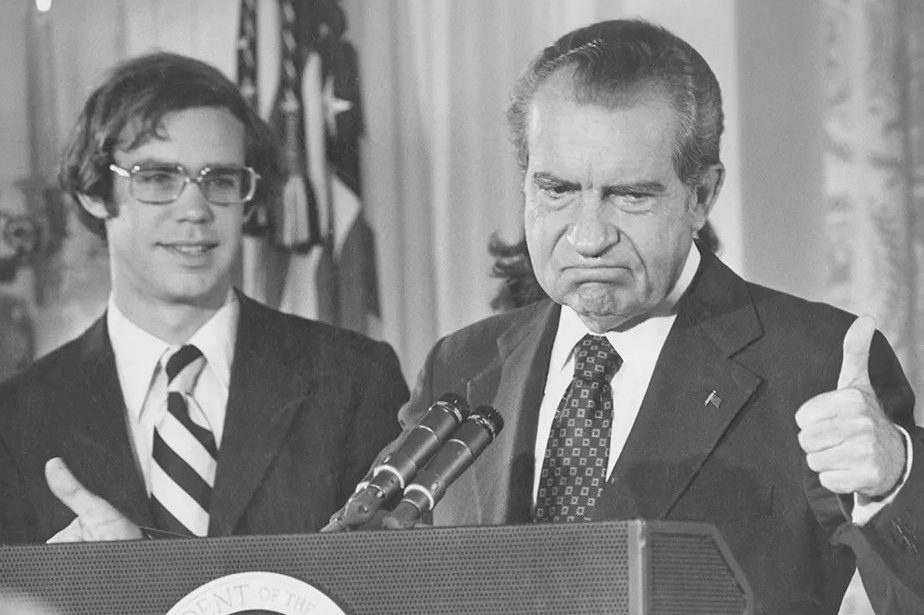

On August 9, Nixon gave a rambling emotional resignation address to his White House staff before boarding the helicopter that would take him to exile in California.

I watched the live broadcast of this exit in my hostess Kay Halle’s crowded drawing–room. Her mansion, 3001 Dent Place, was known to many Brits as the Halle Hilton. Her Anglophilia dated back to the 1930s, when she was engaged to Randolph Churchill, and made her home a port of call for many English journalists, who that day included Alistair Cooke and Henry Fairlie. But her drawing room that morning was mainly packed with notable US congressmen, columnists, former Kennedy aides and prominent Democrats. Few of them could contain their enmity towards Nixon. It was an angry scene, typical of its time.

Some months later, when Ziegler was visiting London, he called to say he had something for me. I invited him to lunch in the House of Commons. “I gave the boss your letter when we were flying back on Air Force One to California on that day,” he told me. “He wasn’t getting much in the way of fan mail, so he was really pleased. Here’s his reply.”

Nixon’s response included this sentence: “If you are ever passing through San Clemente, do come and see me.” It was too good an invitation to refuse. I stayed in the compound of what was once called the Western White House, again with Diane and Frank, who had gone into exile with the ex-president to help with his memoirs.

My meeting with Nixon lasted more than two hours, and a friendship began. Fifty years on I cherish my memories of this extraordinary, talented statesman who — warts and all — is now climbing up the approval ratings of history. I doubt we will say the same about President Biden half a century from now.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply