As Enoch Powell pointed out, “all political careers end in failure.” More often than not, those failures are self-inflicted. Without Partygate, for example, Boris Johnson might still be Britain’s prime minister. Although the debacle may not have been the final nail in his professional coffin, it certainly arranged the wake. His fans and critics alike were infuriated by the idea of public servants living it up while the rest of the nation was locked down during Covid in May 2020. That sort of scandal, however, is nothing new — anger at Partygate is nothing to some earlier episodes in history.

Alexander the Great was an Olympian boozer who habitually went on weeklong binges after subjugating his enemies. During one particularly debauched victory party, a Greek courtesan by the name of Thaïs persuaded the wine-soaked warlord to burn down the imperial palace in Persepolis as retribution for the destruction of the Acropolis by Cyrus the Great a century before. Alexander acquiesced and ordered the ancient citadel to be razed to the ground. When he awoke the next morning and left his tent, pitched outside the city, he instantly regretted the decision, fell to his knees and wept. News of the incident must have horrified the Persian people. In one moment of madness, the Macedonians had demolished the spiritual center of their empire. Later in his Asia campaign, Alexander got into a drunken brawl with his childhood friend, Cleitus the Black, and ran him through with a lance. Cleitus had taken issue with the bloodthirsty boy-wonder’s adopting “barbarian” dress and customs — a development that enraged many of the Macedonian rank and file. Although we have no accounts attesting to overt dissent in the aftermath, Alexander’s murder of his close friend would have further alienated him from his already disgruntled troops.

Rome’s Caesars were perhaps the most sybaritic group of leaders in Western history. Accounts of their luxurious gatherings are scattered through the annals. Suetonius tells us that when Tiberius tired of the daily management of his domain, he took up residence on the island of Capri and entrusted the governance of the empire to his attentive secretary, Sejanus. Sejanus oversaw a season of political trials — kangaroo courts that claimed the lives of hundreds, maybe thousands. While these bloody injustices were being carried out in Tiberius’ name, the emperor was busy arranging decadent orgies at his island villa, orchestrating elaborate group arrangements and scandalizing even the louche with his behavior with children. The pious gentry of Rome were disgusted by Tiberius’ conduct, but none dared rail against him.

His successor, however, was even worse, and his name has become synonymous with dissipation and depravity. Caligula converted the palace of his adoptive grandfather Augustus into a brothel and insisted that the most prominent members of Roman society attend his dizzying bacchanals, whore out their wives and participate in the ensuing excesses under threat of execution. When Caligula’s stuttering uncle Claudius inherited the golden laurels after the former’s assassination at the hands of courtiers and guards, the citizenry was relieved that the worst wantonness was behind them. They were mistaken. Enter Messalina — Claudius’ sultry young wife. Her lewd jamborees mired the house of the Julii in greater scandal than ever. On one occasion, she challenged the most promiscuous prostitute in Rome to a sex-off. According to some, she won hands down, bedding dozens in one sitting. Or lying. Or some combination thereof.

In 1393, in the middle of the Hundred Years War, the Valois dynasty was rocked by tragedy on a Shakespearean scale. The court held a charivari — a masquerade party — at the Hôtel Saint-Pol in Paris. Six attendees, including King Charles VI, wore resin-soaked wildman costumes woven of flax, grass and green leaves. The celebrants met in a small chamber atop a watchtower and drank and jigged late into the night. The King’s brother, the duc d’Orléans, is said to have absentmindedly carried a candle into the rave. The moment it touched one of the flammable costumes, the great flower of French nobility went up in flames. Four out of the six perished in agony. The king was saved by a lady who threw her dress over him. One baron leapt into a barrel of burgundy to dodge the inferno. When the peasantry learned of the disaster, rumors ran rampant that a coup had been attempted or a satanic ritual gone wrong, a punishment from God being exacted on an impious court. The intrigue was so intense that the French royal family did penance at Notre Dame, proceeding there on foot in a gesture of humility. The bal des ardents — of the burning men — cost the Valois political capital in a time of war and weakened the beleaguered country’s already low morale.

In 1501, a Borgia sat on the papal throne. Widely deemed the most lecherous pontiff in the whole history of the Vatican, Alexander III presided over a veritable wellspring of ignominy. But of all the misdeeds and transgressions ascribed to him and his obstreperous children, none shocked and offended so deeply as the notorious night his son, Cesare, hosted an orgy in the papal palace in the heart of St. Peter’s. This Banquet of Chestnuts or Joust of the Whores included cavaliers and courtesans and reputedly climaxed with the two groups openly and energetically liaising. Prizes were offered for stamina and imagination. It would be reasonable to credit this incredible tale to contemporaneous anti-Borgia propaganda, but our sole eyewitness account of the occasion comes from the papal master of ceremonies, Johann Burchard, who was tasked with keeping an eye on Alexander’s administrative costs. He drily jotted down every expense and relevant detail. Discouraging their allies and emboldening their adversaries, word of that wild night undoubtedly increased the Borgia family’s reputation for impiety and hedonism.

In 1903, the Romanovs hosted a massive ball at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, arguably the last spectacular social event in Russian imperial history. The dance lasted three days and was enveloped in the glittering finery and silken splendor the czar’s family were famed for around the world. But while the government waltzed, the people starved. Stories of the lavish ball infuriated the urban poor and provided another example of the czar’s detestable detachment from his impoverished subjects. As one Grand Duke in attendance noted, “a new and hostile Russia glared through the large windows of the palace … while we danced, the workers were striking and the clouds in the Far East were hanging dangerously low.” Even in the blinding glamour of that three-day blowout, some revelers could sense the bloody revolution on the horizon.

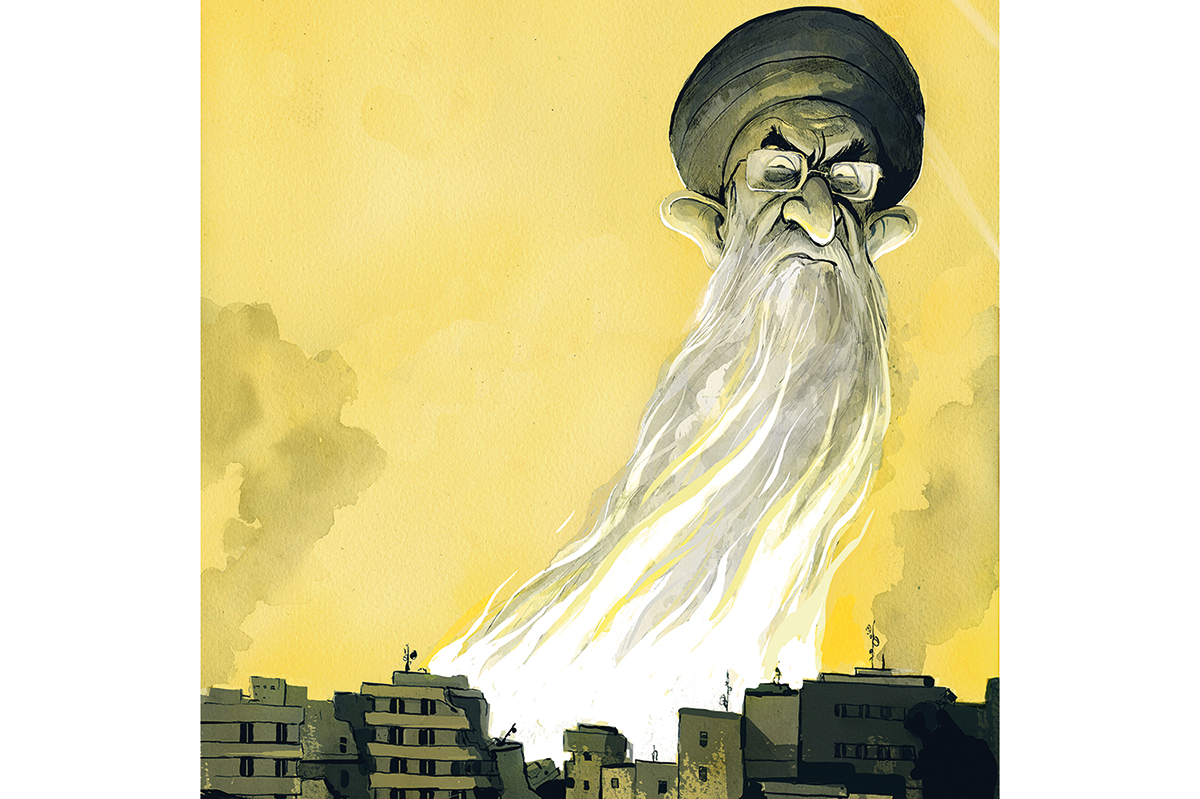

These episodes are dwarfed in comparison to the last Shah of Iran’s monumental 1971 banquet to mark the 2,500th anniversary of the Achaemenid Empire. Mohammad Reza Shah, the King of Kings, erected a city of tents in the ruins of Persepolis to honor the historic milestone and spoke beside the tomb of his illustrious forebear Cyrus the Great. The level of opulence was astounding. The designs and decor resembled fantastical scenes from a Persian fairy tale. One anecdote tells of the Shah importing 50,000 birds to be released at some climactic moment during the festivities. The flocks are said to have died due to the desert climate. Cost estimates range widely, but some say the equivalent of the national budget of Switzerland for two years was spent in two days to pay for the extravagance. In a period of terrible poverty, Reza’s extraordinary decadence outraged both the opposition and the unaligned, uniting most of the country against him. Exiled after the 1979 revolution, the mournful former empress of Iran conceded the part that display of profligacy played in her husband’s dramatic downfall.

Oddly enough, the excessive tastes and untoward habits of some leaders can endear them to the general public. Rascals and rakes such as the French revolutionary Mirabeau, the Whig leader Charles James Fox and even — at times — Silvio Berlusconi have been celebrated for their exorbitant appetites when they weren’t being admonished, or in Berlusconi’s case, prosecuted for them. I suppose it can be reassuring to feel an affinity with your leaders — how better than through a shared sense of fun. Leaders need to let off steam like the rest of us, but often their relaxations offend. When you’re at the top of the pile, too much pleasure will always warrant punishment.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply