In Texas the customers have opinions, and the opinions are always right, no matter how wrong. It was carbonara that taught me this crucial lesson. The diners at the restaurant where I worked brought the American talent for innovation to modifying what I had always considered a fairly simple, self-contained dish.

Can you add fried chicken? Can you add grilled shrimp? Can you add meatballs? Can you add tomato sauce and meatballs? Can you do it without guanciale, without egg, without cheese? Can you do it like normal but put a fried egg on top? Can you replace the guanciale with a fillet of salmon? The answer is always yes.

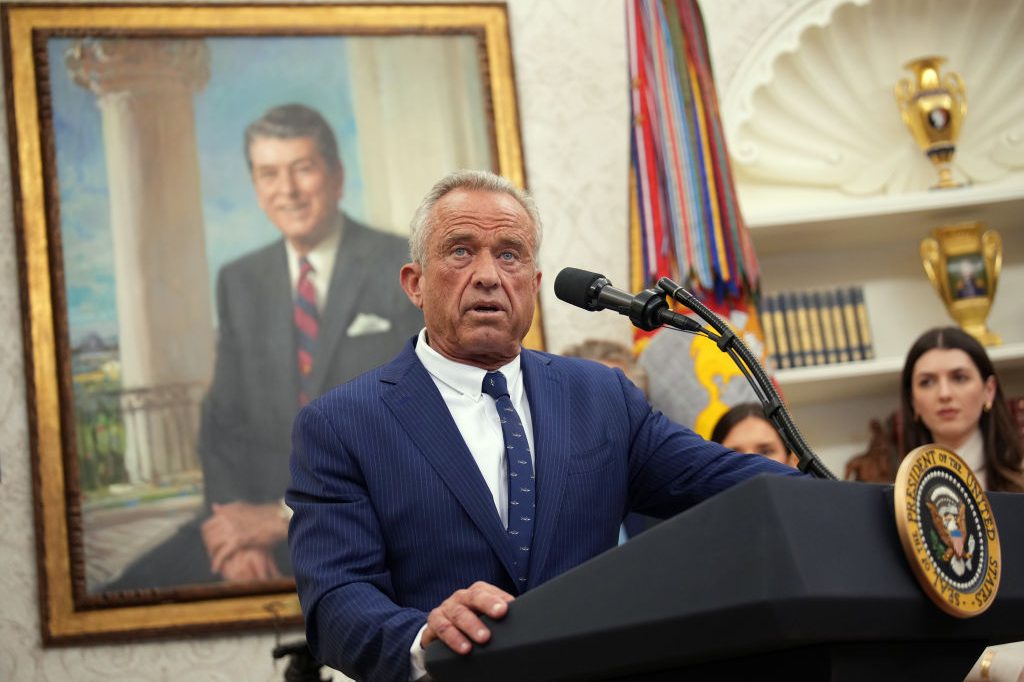

At the time, I was cooking at a neighborhood Italian place in a leafy part of Austin full of well-off old hippies, professional families and Texas politicos. You’d see a guy with a stringy gray ponytail who’d played bass in Jerry Jeff Walker’s backing band sitting one table over from Karl Rove. The restaurant was good but not somewhere that could afford to be snooty about its clientele roaming off-menu.

I was naive about the American style of hospitality. I’d trained in a fashionable London restaurant known for hyperlocal Italian cooking. It listed the provenance of each dish on the menu by subregion. Half the kitchen staff was Italian and most of the dishes were new even to them. We prided ourselves first on hardline authenticity, then on how good the dishes tasted. What the customer wanted was a distant third.

So it took a little time to get used to the requests. The first few times the tickets came through, with modifications printed in scarlet, I asked the head chef if the waiters had made a mistake ringing in the tickets. Maybe they pressed the wrong button?

“No, I don’t think so.”

“They want me to add the tomato sauce straight into the pan with the carbonara? Or, like drizzled on top?”

“What do you reckon?”

“I don’t know, it seems very odd to me. I’m pretty sure they don’t want this.”

“The customer’s always right.”

He shrugged and turned away. He pretended to check with the waiters just to humor me. I scowled at the plates of spaghetti I desecrated, with a sharp bitterness in my voice as I acknowledged the requests.

It became clear I was making no headway — my grumbling and wounded pride seemed to have no effect on the customers’ ordering choices. I took to lecturing the servers individually, explaining that the sweetness of shrimp didn’t really go with the savory richness of emulsified egg yolk, salty pecorino and guanciale fat. They looked at me and nodded.

Nor did the other chefs really get why I was so worked up about the sanctity of carbonara. Most were recently arrived immigrants from Central America and Mexico or assorted Southern misfits, with no emotional attachment to the specifics of a Lazian pasta dish. Of course they would always agree that the customers were morons, or mad, or destined for an immediate coronary. But they didn’t get the carbonara thing.

Eventually my outrage became a kind of vaudeville act for the servers’ amusement. They’d ring in a gimmicky ticket and wait at the pass to watch my reaction. I’d throw my arms up, double check the ticket, shake my head, show it to the chef beside me and look all around for the server, who was invariably standing there laughing. Before I even said anything else, I acknowledged, “Dude, I know, that’s what they want though.”

I don’t know if it’s fast-food chains or tipping or the fetishization of choice or rugged individualism that makes the American diner think he can just add or subtract whatever he likes from a dish or that more garnishes equate to more flavor. It might require a full study of immigration, capitalism, the history of dietary science, identity formation and cultural loss to really understand why Americans put shrimp on carbonara.

But as the months went by I began asking myself another question — why was I getting so exercised about another country’s food traditions? After all, we were in Texas. One of the most common phrases in restaurant kitchens is “in my old place we did it like this.” It’s normally met with a frosty stare or a raised eyebrow; several times I caught myself saying, “In Europe we do it like this.” Once I think I even began a sentence with “As a European…”

I had found the Italian chauvinism frustrating at my old restaurant. After I made a ragù-related misstep I was told to ask an Italian, any Italian, before I made ragù in future. I was told repeatedly that this nationality or that ethnicity could never make “proper” pasta. It was a particularly banal form of nationalism, and here I was perpetuating it without even being Italian.

One day, finally, I fully lost my faith in my own rightness when I read about a renegade Italian pasta historian, Luca Cesari, who demonstrated that carbonara was, in part, an American invention, created by an Italian using GI rations for American troops during World War Two. The first known recipe was recorded in a Chicago cookbook in 1952. Worst of all, the earliest Italian mention, a year later, uses gruyère, garlic and deliberately scrambled eggs.

I surrendered my crusade, put down my tongs and gave up. Maybe the customer is always right.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply