You must remember this… Harry Morgan is leaning on the bar wondering how the femme fatale and her wounded freedom fighter husband are doing. Then Slim walks in, wearing two wisps of black satin linked by a hoop around her navel. Harry tells her it’s time he checked on his patient. “Give her my love,” says Slim. “I’d give her my own,” says Harry, “if she were wearing that.” And in real life, as the tabloids would say, he did.

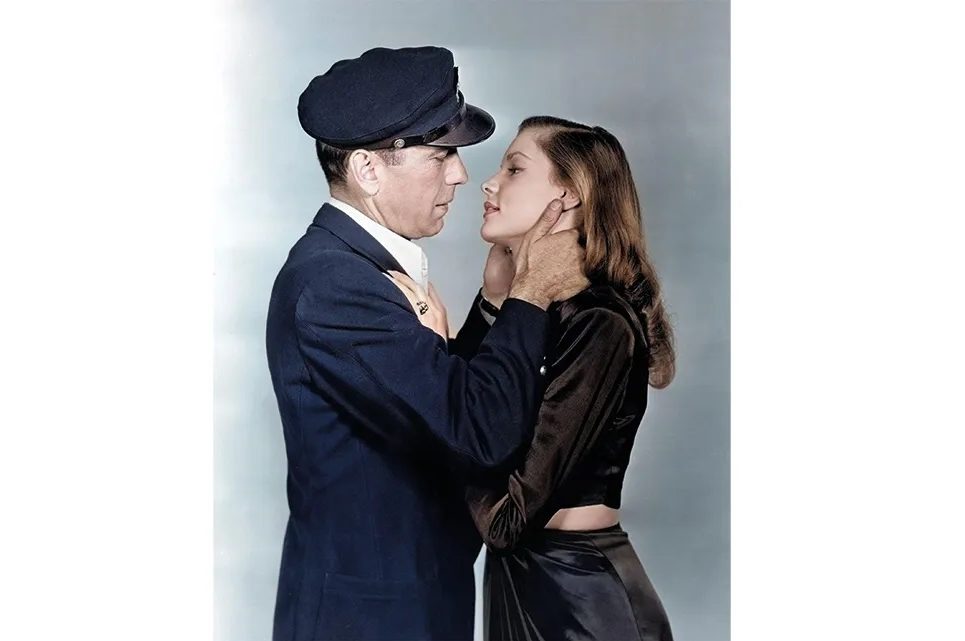

We are talking of To Have and Have Not (1944), in which Harry is Humphrey Bogart and Slim is Lauren Bacall. The director, Howard Hawks, said the movie was just an excuse to do some scenes. Certainly the screenplay he wrote with Jules Furthman and William Faulkner, adapted mighty freely from what he had told Ernest Hemingway was a “god-damned bunch of junk” novel, makes even less sense than Papa’s original. But those scenes still zing: Walter Brennan’s rum-sodden wreck being interrogated by les flics; Bacall crooning “How Little We Know” with the song’s writer, Hoagy Carmichael, at the keys; Bogart ruffled from lethal cool when Bacall tells him that if he wants her, just “put your lips together and blow.”

Alas for Hawks, the really big scene he had in mind never made it past his private dream factory. He wanted Bacall, who his wife had spotted modeling in a fashion glossy, for himself. He had her flown from New York to Los Angeles for a screen test. He taught her to lower her chin so that as she gazed upward at the camera she somehow looked both coy and coquettish. He had her learn to lower her voice (by shouting Shakespeare in some Californian canyon). Then he put her under a personal service contract and set about bedding her.

Enter Bogart. He was as old as the century — which meant he was more than twice the twenty-year-old Bacall’s age. Well, older men have always chased younger women. And a new kid on the block can be forgiven for hoping that playing along with the fantasies of a seasoned pro might smooth her career path. In other words, it wasn’t quite love at first sight. Bogart was extricating himself from a third failed marriage — a liaison so dangerous he had taken to nicknaming his wife “Slugger.” But the movie’s script was so sassy and sexy and innuendo-ridden it might as well have been called “Carry On Flirting,” and Bogart and Bacall began to take it for gospel. In May 1945, mere months after the movie’s release, they were married.

Catherine Curzon would regard that last paragraph as cynicism worthy of Bogart’s Philip Marlowe. In The Real Bogie and Bacall she paints the couple as star-crossed lovers beside whom Shakespeare’s poetry pales, a Tristan and Isolde so in tune they make Wagner’s harmonic suspensions sound like porno muzak. It would be wonderful if it were true — but only in the movies is love that lovely. So in 1942, while still married to that third wife, Bogart started an affair with an actress turned toupée-maker called Verita Thompson that would last until not long before his death in 1957.

We know that Curzon knows about this, because she mentions it before dismissing it for not fitting in with her theory that “Bogie’s years with Bacall were his most contented.” I don’t doubt that she’s right about that contentment. But a biographer ought to be able to entertain the notion that her subject can be both happily married and playing away. The lesson of Bogart’s essential films (as well as To Have and Have Not, that means Raoul Walsh’s High Sierra, Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca, Hawks’s The Big Sleep, and Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place) is that romance is always an intrigue, and that only in our daydreams does boy meets girl mean living happily ever after.

But then Curzon doesn’t know her movies. Like Bogart’s Rick, who “came to Casablanca for the waters,” she’s been “misinformed.” It was Woody Allen, not Bogart, who said that sex is the most fun you can have without laughing. Far from being “accused of a murder we know he didn’t commit,” the Bogart character in In a Lonely Place is a crazed sociopath whose story the cops have every right to doubt. As for the suggestion that Bacall wanted to be “the sort of bride Doris Day played,” that was some wish considering that Bacall married Bogart three years before Day’s movie debut — and eleven years before she was cast as a wife.

Curzon’s wildest folly comes when she argues that Bogart was “authentic to his last breath.” Let the record show, then, that Humphrey DeForest Bogart was born to the kind of Upper West Side Manhattan family that had a summer home on Canandaigua Lake; that the boy was dressed like Little Lord Fauntleroy; that he was sent to dance classes. If authenticity is your thing, then the young Bogart who spent his Broadway apprenticeship wearing white flannel while minting the line “Tennis anyone?” is a lot closer to life than the tough-guy reveries of The Roaring Twenties or The African Queen. But who watches a Bogart movie for authenticity? You watch Bogart for the same reason Sydney Greenstreet wants The Maltese Falcon’s titular bird — because they’re “the stuff that dreams are made of.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.