This is a book like no other. Part artwork and part compendium of a lifetime’s experience in design, it is meant to be looked at as much as read. Nor is it titled Colorful for nothing: entire pages are in vivid hues of vermilion, lime green, canary yellow, emerald and toffee. On them are displayed illustrations, patterns of fabric and family photographs, interspersed with chunks of prose or aphorisms. In short, it is an expression of its author’s philosophy, threaded through rather disjointedly with the story of her life.

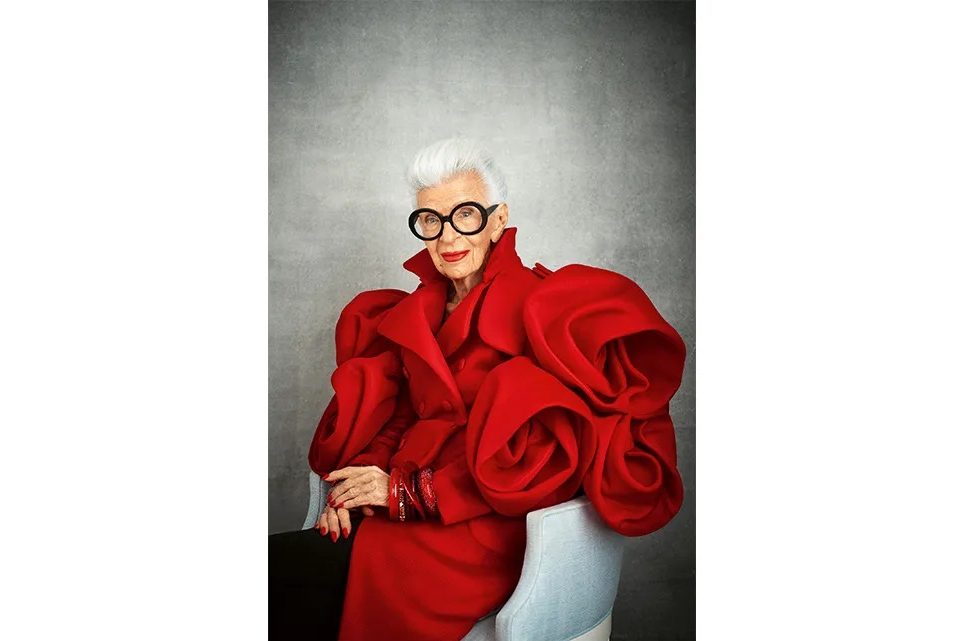

Iris Apfel is the only woman I can think of — with the possible exceptions of Diana Vreeland and Helena Rubinstein — who turned extreme plainness into an aspect of personal style. She was instantly recognizable with her huge round spectacles, bright red lipstick, waterfall of necklaces and her ensembles, that were, to say the least, original. In President Nixon’s time, since she thought the White House underheated, she attended a meeting with him wearing the thick tunic of a priest, accessorized with thigh-high boots and an armful of chunky bangles. She took no notice of fashion, although Vogue called her “one of the industry’s oldest taste-makers.”

Apfel died earlier this year, but not before, approaching her 102nd birthday last summer, she had completed this volume, described by her as her “legacy” book. She begins with a personal credo:

Color… affects how we think, feel, see the world. The colors that resonate with us are a visual representation of our personalities. We need color in our lives because life can be very drab — on the worst days, an absolute wasteland.

Photographs of Iris herself illustrate this. Here she is with every inch swathed in brilliant red (‘pastels make me nervous’); there in canary yellow; on another page in dramatic monochrome.

Born Iris Barrel to a mother who kept a fashion boutique in New York and a father who supplied mirrors and glass to decorators, she was always a magpie-like collector. Her weekly treat when young was a subway ride from the Barrel home in Queens to the antique shops and flea markets of Greenwich Village. There she would haggle for what-ever took her fancy — a piece of some antique fabric, Native American beadwork, African bangles. She studied art history, worked briefly as a journalist and in 1948, aged twenty-six, married the thirty-three-year-old textile merchant Carl Apfel.

Iris was instantly recognizable with her huge round spectacles, bright red lipstick and waterfalls of necklaces

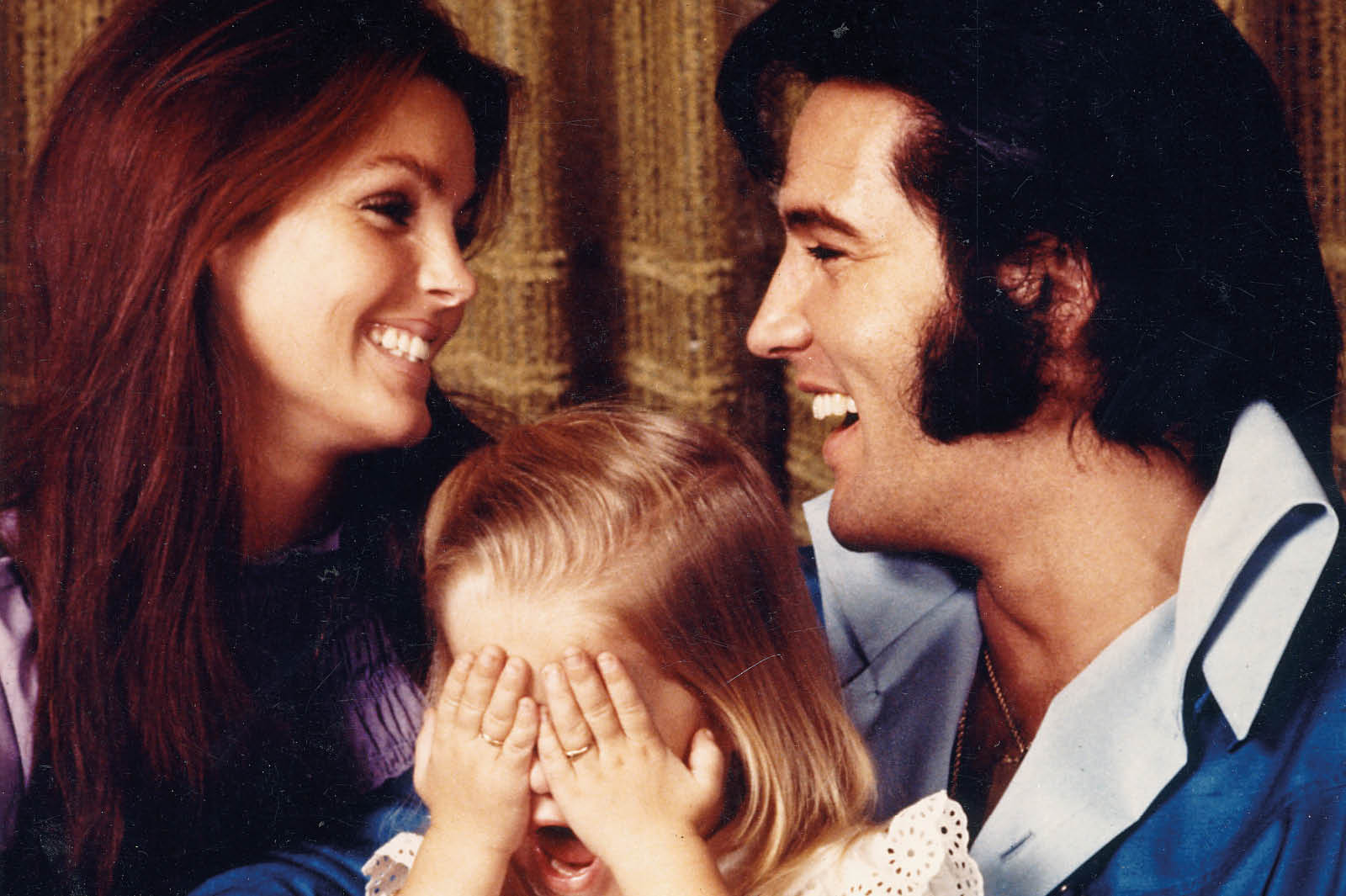

For the next sixty-seven years they were never apart, living, working and traveling together. After World War Two, furniture and fabrics were in short supply, so when Carl could not find the right cloth for a period décor, Iris would adapt a design from an old piece of fabric she had bought on one of her forays into junk and antique shops and they would have it woven at a friend’s textile mill. In 1952 they set up Old World Weavers, sourcing antique textiles from all over the world or, if they could not find them in souks or bazaars, making copies. His was the business brain, hers the eye. Soon they had carved out a niche for themselves, working for ten presidents in all, from Harry Truman to Bill Clinton.

The fabrics shown in this book are wonderful — somehow the textures leap off the page. In the 1960s the Apfels had a runaway hit with their “Tiger” silk velvet, a bold, black and gold, fifty-four inches wide pattern, handwoven in Venice but alas not shown here. Other pages are devoted to Iris’s vast collection of jewelry. Never was she seen without more of it than most people would wear in a month (“more is more, but less is a bore” is another of the book’s mantras). There were cascades of turquoise beads, chunky bangles worn from wrist to elbow (usually on both arms), outsize earrings, black and diamanté deco bracelets, intricately worked silver beads and glittery paste butterflies.

Then, in 2005, came real fame. A costume exhibition at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art had fallen through at the last minute, and its designer, who knew Iris, asked her if she would be willing to display her own vast wardrobe and collection. It was an instant hit, as was she. What enthralled people was her originality. “If you don’t dress like everyone else, you don’t have to think like everyone else,” she writes here.

As one who was signed up by a modeling agency at ninety-seven, her views on old age are equally trenchant:

Getting old ain’t for sissies, it’s true. But age happens… You might start falling apart but you have to keep going, keep pasting yourself together. It’s so important to be busy.

But perhaps the key message of the book is the importance of originality, in the sense of finding your own style while always being open to new ideas and having the courage to put them into practice — of not being afraid to be individual, in fact. As she observes, fashion can be bought (“in New York you can sometimes tell a person’s zip code by the way they dress”). But “style is something you own. What’s important is attitude, attitude, attitude.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.