For a brief moment three summers ago it seemed that the clear Idaho air wafting through the Sun Valley Literary Festival had become tainted with the smoke and soot of Nuremberg. Here was Thomas Friedman, bloviator-in-chief to America’s chattering classes, standing before a rally of thousands, delivering a powerful philippic about the ascent of the Asiatic East.

As he warmed to his theme, he decided for some messianic reason to demand that his audience chant the phrase that he suggested now dominated the American economic landscape. Come on, he urged like a latter-day Elmer Gantry, yell out with me the words: ‘Everything. Is. Made. In. CHINA!’ And, as one, the thousands complied, and roared, and the hills suddenly came alive with the sound of ‘China’ echoing like some awful warning.

The Chinese Question was in the headlines again, as it remains three years on. And though most of history’s other tabloid interrogatives — the Jewish Question, the Woman Question, the Negro Question — have been settled, more or less, the Chinese Question remains, and seems likely to do so for some while to come.

Mae Ngai, who teaches history at Columbia University, has long been interested by the marginalized and migrant of the world’s workforces. She is particularly fascinated by the Chinese around the world who fall into both categories. Her latest important and eminently readable book takes on the challenge of speaking the unspeakable and asking the unaskable: why do so many white people continue to loathe, suspect, disdain, fear or otherwise shun so many of the ‘Celestials’ (as we once knew them), and in doing so sustain the Chinese Question decades after it should have been laid to rest?

Gold is at the root of it, Ngai suggests. Since mid-Victorian times, three great gold rushes — in the Americas, South Africa and Australia — managed to win from the earth tons upon tons of the precious stuff, which helped bring this bullion into circulation to create the monetary basis for modern capitalism. In all three rushes, Chinese workers — enticed, cajoled or coerced, and first drawn mainly from the Pearl River lowlands between Canton and Hainan — were shipped out from the eastern seaports in their tens of thousands. Making contact with white men for the first time, they then began the heroic work of separating glittering nuggets from the gravel, dust and grit of the Sierra and the Yukon, Ballarat and Bendigo, the Bushveldt and Transvaal.

Dismissed unthinkingly as ‘coolies’ by most white settlers, these men worked fantastically hard, with precious little complaint. The Irish, Dutch and Italian immigrants who labored alongside them — a far less energetic workforce who liked a beer and a snooze in the afternoon — came to loathe the Chinese for their endurance, industry and seriousness, and probably also for the privacy of their community, with its unfamiliar rituals, food and language. Out of this welling hatred was born the Chinese Question, a rhetorical device which still lingers and is neatly summarized by Ngai: were the Chinese a racial threat to white countries, and should they be barred from them?

The specific threat was that the ‘Heathen Chinee’ would eventually take over the countries to which they had migrated. An Australian newspaper cartoon of 1886, ‘The Mongolian Octopus’, displayed the process — a white population being gradually choked by tentacles labelled smallpox, immorality, fan-tan, opium, bribery, typhoid and cheap labour. Then again, it would be ‘South Africa for the Chinese!’ if the China-loving Tories won Britain’s 1906 election, according to the Liberal party’s highly effective fear-mongers — rhetoric that had Arthur Balfour soundly trounced.

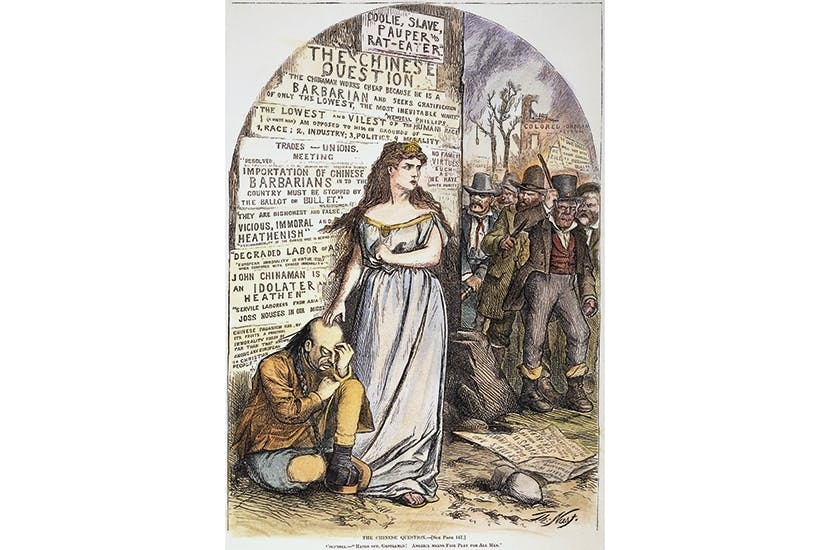

America also felt menaced. In the 1870s, an alarmed, sympathetic Thomas Nast famously drew defiant Columbia, a lady trying to protect a despairing Chinese man from a furious Irish mob, cudgels at the ready, who threaten him as a ‘barbarian’, ‘rat-eater’ and ‘vilest of the human race’. But sympathy was in short supply on Capitol Hill. In 1882, Congress passed its notorious Chinese Exclusion Act, removing all protection and forbidding immigration from China until 1943. (It strains credulity to remember its longevity.)

Now the Chinese Question is back with a vengeance. In fact it never really went away, says Ngai: ‘The idea that China poses a threat to Euro-American civilization has remained just beneath the surface.’ Inflammatory rhetoric is everywhere again. From Donald Trump’s Kung Flu and Wuhan Virus to Friedman’s wild assertion about ‘everything’ being made in China (in fact only 21 percent of US imports are), the US in particular is becoming increasingly alarmed, its population lashing out in an orgy of anti-Asian street violence not seen for a century.

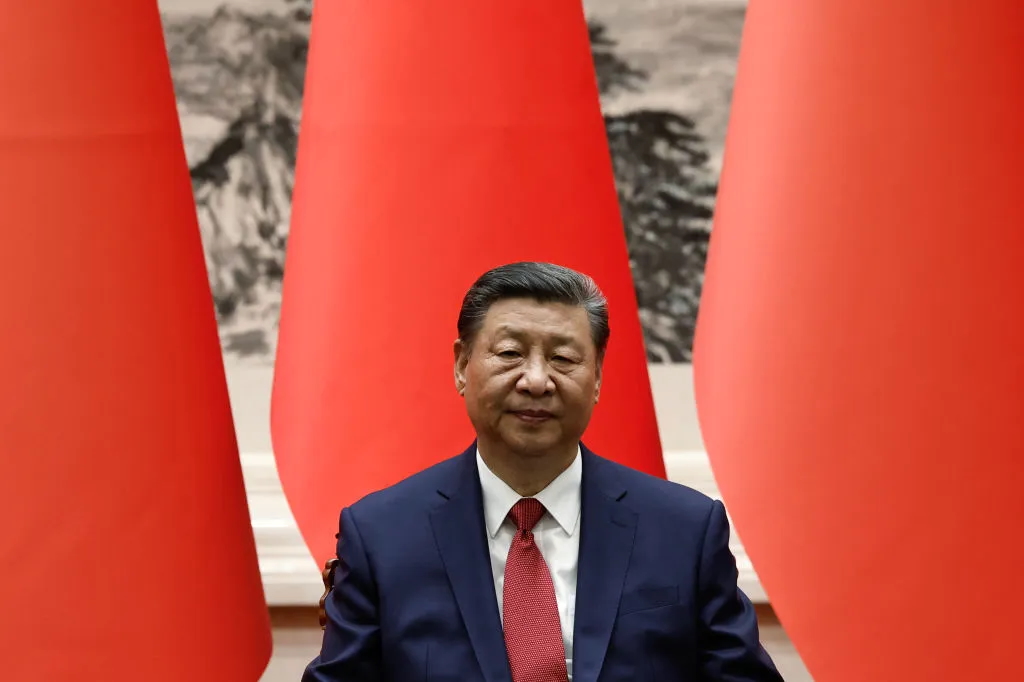

Mind you, matters are hardly helped by recent official Chinese rhetoric, though President Xi Jinping’s threatening bluster — those who interfere over Taiwan ‘will have their heads bashed bloody’ — is not so new. Back in 1995, reports came of a huge poster mounted outside a Chinese space research centre in the Gobi desert which proclaimed in English: ‘Without Haste. Without Fear. We Conquer the World.’ There is a confidence, a swagger, which seems taunting and dangerous.

The Chinese, who have excelled at so many things since ancient times, seem to be reminding us barbarians on the outside of the nature of their historic superiority. In recent centuries this related simply to the extraction of gold. Now, as Ngai presciently notes in a book that valuably places today’s argument in context, it has implications for the entire world.

Given the inherent perils, perhaps those on both sides should calm themselves, and approach the Chinese Question more dispassionately. The coolie myth is over. China requires, and demands, what has been lacking ever since the first migrant laborers arrived in California. It says it deserves respect. We should be listening carefully.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.