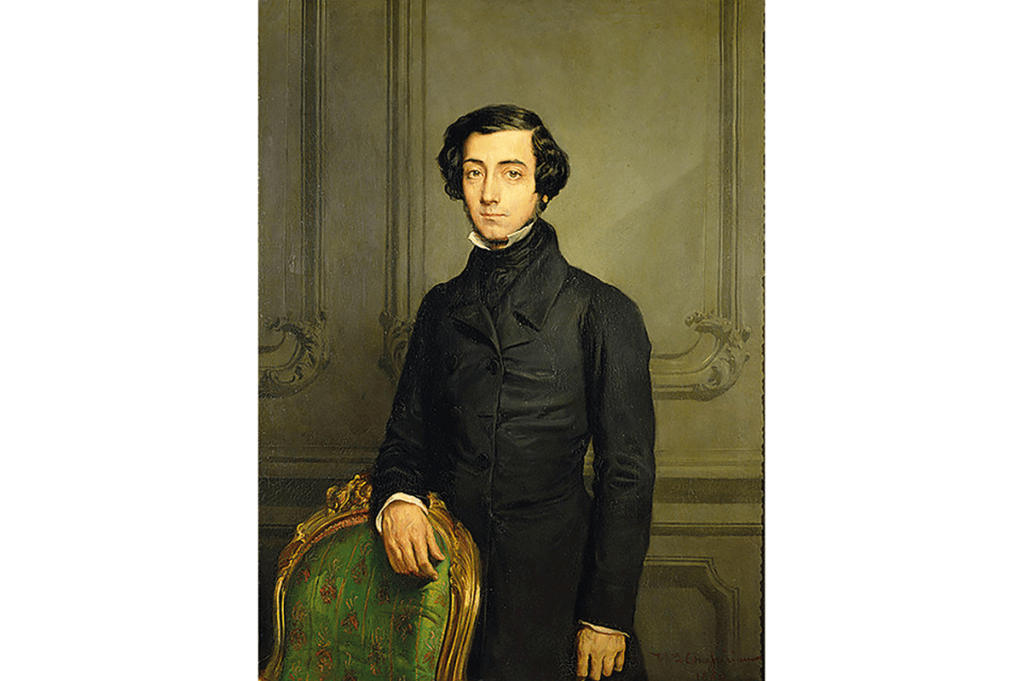

Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-59) produced what his biographer Hugh Brogan called “the greatest book ever written on the United States.” Among the most remarkable things about this work — Brogan was referring to the first volume of Democracy in America, not the more abstract second volume — is that Tocqueville’s journey to the United States lasted just nine months, and was undertaken when he was in his mid-twenties, never to return. Yet the book’s publication, when Tocqueville was still only twenty-nine, made him an instant celebrity.

The young French aristocrat was especially pleased by its reception in America, where an unauthorized edition was published in 1838. He wrote to his friend Gustave de Beaumont, with whom he’d made the trip, about a review by a Harvard professor called Edward Everett:

What particularly impressed me was the praise for my impartiality and above all for the great truthfulness of my portraits… I was afraid that I might at times be making monumental errors, principally in the eyes of the people of the country.

‘Of all modern peoples, Americans have pushed equality and inequality furthest among men’

The acclaim was not universal, of course, and several scholars have subsequently taken aim at Tocqueville’s reputation, accusing him of making sweeping generalizations based on a whistlestop tour in which he rarely ventured beyond the company of the social elite. “A fact usually omitted in discussions of Tocqueville is the shallow empirical basis of his study,” wrote Gary Wills in the New York Review of Books in 2004. Tocqueville has been upbraided for failing to notice the rapid industrialization that was taking place during his visit, as well as being indifferent to the suffering of the black population, a sin he repeated on a later visit to Algeria, where he praised French colonialism. Even at the time, American critics took issue with his warnings about “the tyranny of the majority” — a constant danger in a democracy, he thought — and attributed it to his having witnessed the presidency of Andrew Jackson, whom he met in Washington and was unimpressed by.

Jeremy Jennings, a professor of political theory at King’s College, London and an expert on the history of French political thought, has set out to rescue this reputation. In a magisterial biography, he retraces the footsteps of Tocqueville, not just across America, but on his other foreign excursions — always with a notebook in hand and driven by a voracious intellectual curiosity. Thus, we accompany the pioneering political scientist, who briefly served as minister of foreign affairs in the short-lived Second Republic, on his trips to Canada, England, Ireland, Switzerland, Algeria, Italy and Germany. We soon discover it wasn’t just on his trip to America that Tocqueville was able to see beyond the view from the carriage window and into the heart of the society he was traveling through.

To be sure, the Comte de Tocqueville, who inherited a castle in Normandy, was not always able to transcend his own biases as a Catholic nobleman (although he lost his faith as a teenager). For instance, he thought the more direct version of democracy that had emerged in Switzerland was less likely to endure than the elaborate representative government he encountered in the US, describing it as “the most lax, powerless, blundering and incapable [system] that one could imagine.”

He also believed that the philosophes of the French Enlightenment had been too quick to declare the Christian faith incompatible with the scientific and democratic revolutions sweeping the world, taking much comfort from the piety of nearly all the people he encountered in America. “When I arrived in the United States, it was the religious aspect of the country that first struck my eyes,” he wrote to his friend Ernest de Chabrol in 1832.

The most astonishing thing about Tocqueville’s work is how many of the observations he made about the new social and political order he saw emerging in the first half of the nineteenth century have endured. His prediction that democracy in one form or another would eventually replace the desiccated systems of government that characterized Europe’s ancien régime — that it was the destiny of all the world’s civilized peoples, not just the English-speaking, to embrace democracy — was remarkably prescient. Even more impressive was his grasp of its shortcomings, prefiguring Churchill’s judgment that democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.

It’s true that by today’s standards he was not as alive to the injustices of the America he journeyed through as he might have been, neglecting to scold his hosts on their treatment of Native Americans as well as the enslaved black population. But, as Jennings points out, he was far from indifferent to it. He referred to slavery as “the most formidable of all the evils that threaten the future of the United States,” and in a deleted passage from the first volume of Democracy in America he wrote: “The Americans are, of all modern peoples, those who have pushed equality and inequality furthest among men. They have combined universal suffrage and servitude.”

He was also sensitive to the suffering he encountered elsewhere, remarking on the extraordinary inequality that characterized Victorian England, as well as the indignities inflicted by the British on the Catholic population of Ireland. Yes, he defended France’s conquest of Algeria and travelled to the interior in the company of the French army, but he was disgusted by Napoleon III’s attempts to create a replica of his uncle’s empire, and was hardly alone among nineteenth-century political theorists in having a blind spot about colonialism.

Was he right about “the tyranny of the majority?” Most western democracies have proved reasonably adept at defending the rights of minorities, putting legal and constitutional protections in place that serve as bulwarks against demagoguery, although there were several glaring exceptions in the 1930s. But when Tocqueville alerted his readers to this risk, he was thinking as much about the psychological cost of challenging the majority view as he was of the political difficulty. He recognized that in a society characterized by “equality of conditions,” in which political questions were decided by a majority vote, there was an absence of alternative sources of authority, which made it hard for mavericks and dissenters to survive.

For Tocqueville, this was the explanation for the extraordinary uniformity of opinion he encountered in America. He wrote in Democracy in America:

In the United States, the majority takes charge of providing individuals with a host of ready-made opinions, and thus relieves them of the obligation to form for themselves opinions that are their own. I know of no other country where, in general, there reigns less independence of mind and true freedom of discussion than in America.

Many American readers, then and now, objected to this criticism; but for most Europeans who’ve spent time in America it is obviously true. I remember going there as a graduate student in 1987 and being struck by the fact that there was a greater range of political opinions among the ten students I’d studied PPE with at my Oxford college than there was in the whole of the Harvard Department of Government. Since then, with the triumph of the Great Awokening, the lack of viewpoint diversity in America’s universities has only got worse. For anyone seeking to understand this phenomenon, Democracy in America is still essential reading.

The scholarship on Tocqueville is voluminous, and retracing his journey across America has been done several times. But Jennings’s book is the first to exhaustively follow him on his travels outside America as well, and provides a highly readable introduction to the work of one of the nineteenth century’s most insightful political theorists, as well as a persuasive defense of his ideas.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.