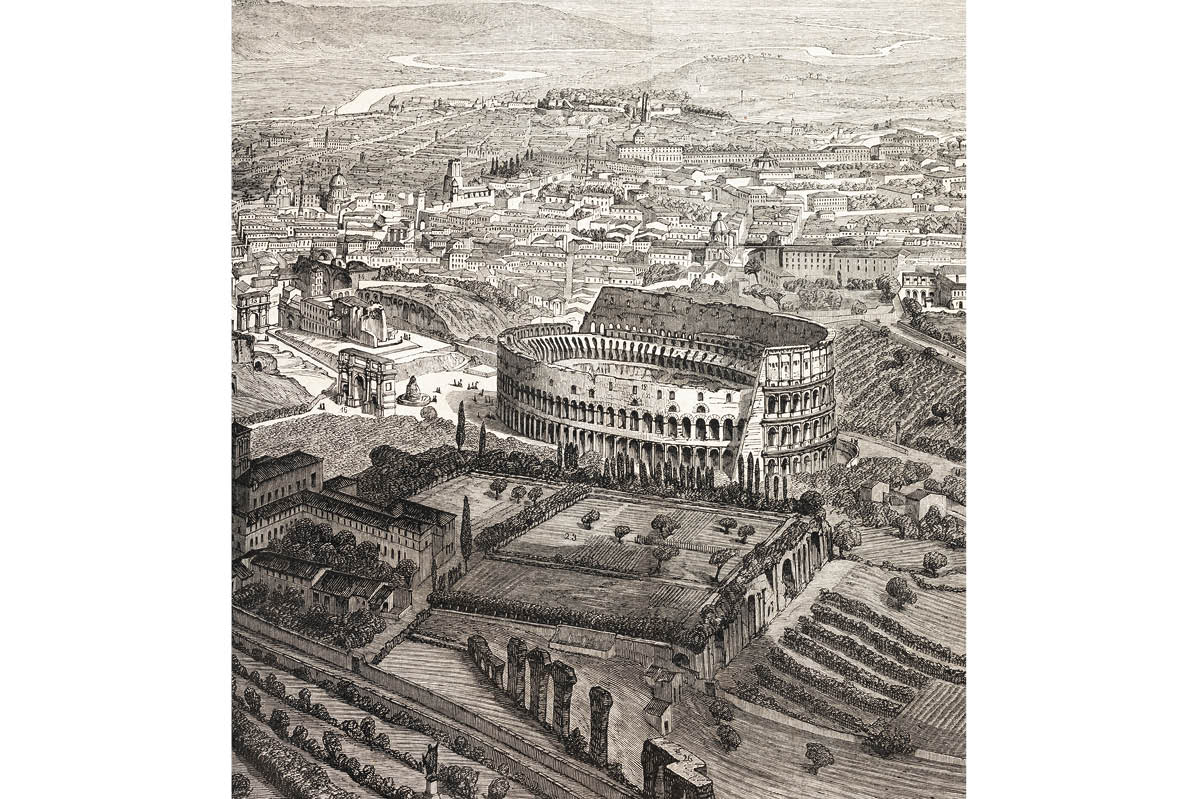

Throw him to the lions! That’s what I thought when I saw the video of a grinning moron desecrating the walls of the Colosseum with the words “Ivan + Hayley 23.” He must have been referring to his girlfriend, standing by his side — and the year. It wasn’t just the fact that he’d defaced the greatest of all Roman buildings. It was that he’d written something so depressingly banal. He could at least have written the year in Roman numerals — MMXXIII. And he could have borrowed some themes from the Romans — the rudest graffiti artists ever.

We like to think of the Romans as highfalutin, high-minded gods. But they swore like us. They were obsessed with sex, like us. And they wrote their rudest thoughts on walls — in a much more obscene way than we do. Just look at the Pompeii house of Claudius Eulogus in Via Dell’Abbondanza. The graffiti artist there echoed my feelings about the idiot in the Colosseum: “Move te, fellator.”

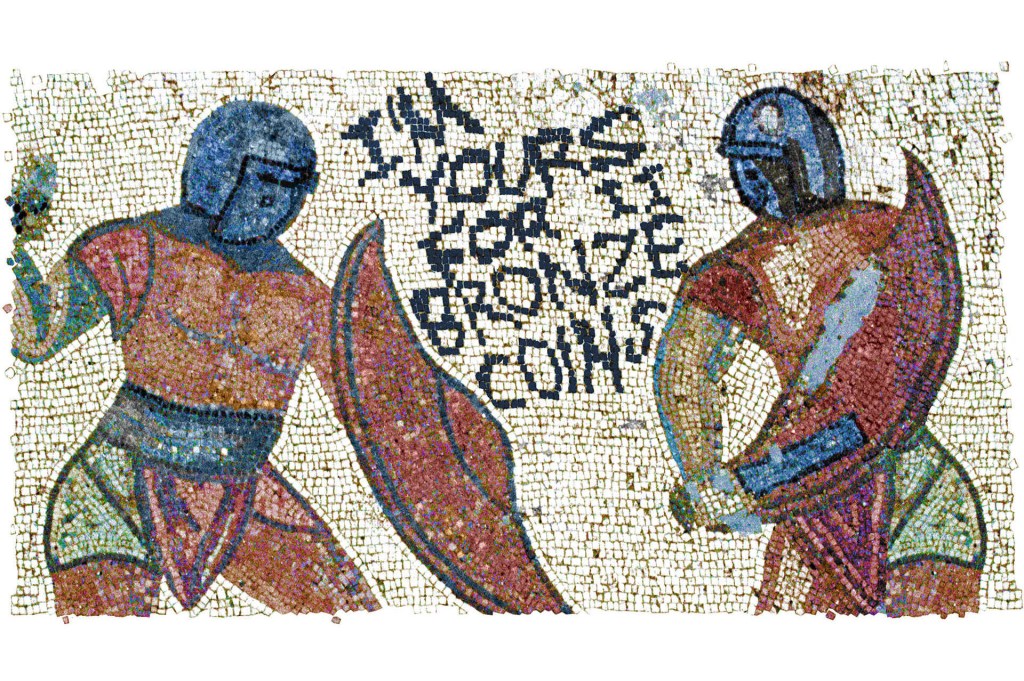

They’re still excavating rude graffiti at Pompeii. Archaeologists recently dug up a thermopolium — or snack bar — revealing the words “Nicia cinaede cacator” — “Nicias [probably a freedman from Greece], you catamite shitter!” On the wall of Pompeii’s basilica, you’ll find the words “Lucilla ex corpore lucrum faciebat” — “Lucilla made money from her body.” Nearby, a prostitute has written “Sum tua aeris assibus II” — “I’m yours for two bronze coins.” That was about the price of two glasses of wine in Pompeii.

Dirty pictures were everywhere, too. The biggest queues in Pompeii are of tourists staring at the frescoes of a couple experimenting in the bedroom. The most popular room in the Naples National Archaeological Museum is the Gabinetto Segreto (“Secret Cabinet”), with rude artifacts from Pompeii and Herculaneum. In the Domus Tiberiana in Rome, there’s a crudely drawn man with an oversized penis for a nose.

Such pictures spread across the Roman Empire. Pornographic mosaics were recently discovered at a Roman latrine in Antiochia ad Cragum in Turkey. They show the beautiful youths from Greek mythology Narcissus and Ganymede admiring their enormous members. But the graffiti could be romantic, too. Who hasn’t felt these love pangs, found at the house of Pinarius Cerialis in Pompeii: “Marcellus Praenestinam amat et non curatur.” (“Marcellus loves Praenestina but she doesn’t care for him.”)

Pompeii’s graffiti can be extremely sophisticated. Take these lines in the house of Cecilius Secundus: “Quisquis amat valeat, pereat qui nescit amare, bis tanto pereat, quisquis amare vetat.” (“Let whoever loves prosper; but let the person who doesn’t know how to love die. And let the one who outlaws love die twice.”)

Or what about these moving words, on the wall of a Pompeii bar?

Nihil durare potest tempore perpetuo;

Cum bene Sol nituit, redditur Oceano,

Decrescit Phoebe, quae modo plena fuit,

Ventorum feritas saepe fit aura levis.

(Nothing can last for ever;

Once the sun has shone, it returns beneath the sea.

The moon, once full, eventually wanes;

The violence of the winds often turns into a light breeze.)

The Pompeii graffiti artists also subtly echoed the great Roman poets. That’s what Fabius Ululitremulus did in his laundry: “Fullones ululamque cano, non arma virumque.” (“I sing of launderers and howling, not arms and a man.”) Fabius was quoting what was then, as it is now, the most famous line in Roman poetry, the opening to Virgil’s Aeneid: “Arma virumque cano” — “I sing of arms and a man.” In Balbus’s house in Pompeii, there’s the apparently simple line “Militat omnes.” It was in fact inspired by Ovid’s line “Militat omnis amans” — “Every lover fights.”

Everyday life is written on the Roman walls, too. In a Herculaneum taverna kitchen, the owner wrote “XI Kalendas panem factum” — “Bread is made on the eleventh of the month.” And just like in Italy today, political graffiti was popular. Again on the subject of baking, in Via Nolana, Pompeii, there’s the political slogan, “C. Iulium Polybium aedilem oro vos faciatis. Panem bonum fert” — “I beg you to make C. Julius Polybius aedile [a magistrate]. He makes good bread.”

When it comes to mistakes in Roman graffiti, Monty Python’s Life of Brian got it spot on. John Cleese’s centurion attacks Graham Chapman’s Brian for messing up his Latin graffiti:

Centurion: “Romans, go home!” is an order, so you must use the …?

Brian: The … imperative.

Centurion: Which is?

Brian: Um, oh, oh, “I”, I!

Centurion: How many Romans?

Brian: Plural, plural! “ITE.”

One Pompeii graffiti writer confused his accusatives with his nominatives, writing “pupa mea” (“my little girl”), when he should have said “pupam meam.” In Sallust’s house in Pompeii, the writer, trying to say “Quae bella es” (“You who are beautiful”), blundered by daubing “Que bela is”

How consoling that ancient graffiti artists, like schoolboys today, made mistakes with their Latin. Still, however bad their howlers, Roman graffiti was always more inspiring than the tawdry rubbish scrawled on the Colosseum today.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.