This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

No one remembers Wendell Willkie. If you don’t believe me, mention him as a man worth looking up at your next cocktail hour. Then watch as even well-informed acquaintances wonder when, exactly, you started taking an interest in adult-entertainment performers or bothered to locate the inspiration for Arrested Development’s hit ‘Mr Wendal’. Even the learned (and let’s throw in friends who subscribe to the New Yorker to even things out), will struggle to recall that Willkie was not only referred to as ‘Private Citizen Number One’ by FDR. He was also a founder of liberal globalism — or a refounder, given how badly Woodrow Wilson’s first attempt had gone.

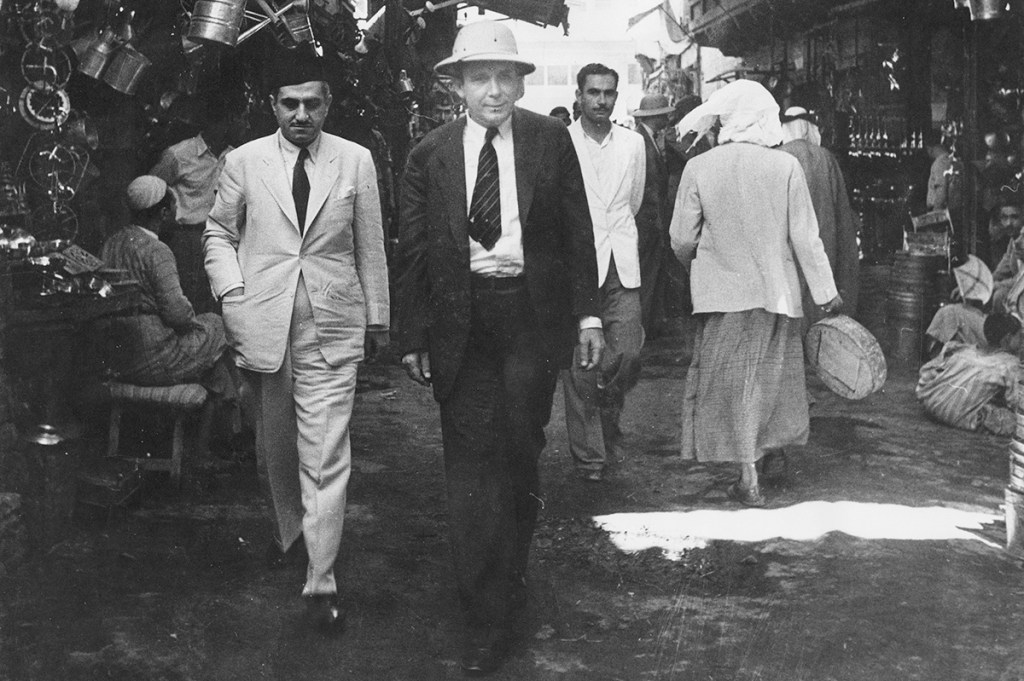

In August 1942, with the United States deep into World War Two, Roosevelt assigned Willkie an unofficial but well-publicized mission to support Allied war recruitment, promote America’s image among its allies and lay the ground for the day when its enemies, having been brought to their knees, could be restored to the family of nations on American terms. As Willkie’s four-engine Consolidated C-87 — appropriately named Gulliver — hopped between countries, he met everyone from Stalin in Moscow and de Gaulle in Beirut to the Shah in Tehran and the Chinese nationalist Chiang Kai-shek in Chongqing. The Idealist is Samuel Zipp’s idealizing and less than ideal account of how Willkie briefly captivated the American imagination.

Willkie already subscribed to the internationalist vision he would refer to in a bestselling manifesto-memoir as ‘One World’. This son of Indiana, his conscience already troubled by domestic failures of government in matters racial, left home with his antennae sensitized to the ill effects of colonialism. His globe-spanning trip — 31,000 miles, seven weeks, 13 countries, five continents — intensified his belief in an interdependent future. Willkie, who never quite recovered from the failure of the League of Nations, became increasingly convinced that America must lead a new world, safe from isolationism, nationalism and imperialism — excepting, of course, the liberal American kind.

Born in 1892 in Elwood, Indiana into a family of lawyers (his mother was one of the first female attorneys in the state), Willkie joined the family business. His brilliance as a trial attorney representing public utility concerns landed him a prestigious Wall Street job with Commonwealth & Southern. He eventually became president and CEO and received national recognition for his performances in the Tennessee Valley Authority hearings of 1938. As the Republican presidential nominee, he lost to FDR in 1940; he would run again for the Republican nomination in 1944, but lose.

Willkie’s internationalism, his support for desegregation and his corporate background failed to charm Republican voters, but they won him an admirer in President Roosevelt. In January of 1941, FDR sent him to England for an 18-day visit as a ‘private citizen’. In London, Willkie barnstormed for the Lend-Lease program and felt the Blitz firsthand. Eighteen months later, he returned overseas as an emissary to wartime allies and an unsettled geopolitical future.

‘Willkie — his trip, his book, and the phenomenon of his sudden celebrity — was an avatar of a precarious moment almost lost to our own cultural memory,’ writes Zipp, who might be overestimating the powers of cultural memory. The bulk of Willkie’s impressions are naïve and generally forgettable. The insight they offer is into the platitudes of the official mind or, more charitably, an honest heart. Turkey has ‘set its face to the modern world’ and is ‘building hard and fast’. China is ‘a warm-hearted, hospitable land filled with friends of America’. Stalin is ‘a hard man, perhaps even a cruel man, but a very able one’.

In April 1943, Willkie cast these pearls of diplomatic insight before the swine of the reading public in One World. Irrespective of the soundness of his observations or the depth of his understanding, Willkie saw that the tectonic plates of the world order were shifting in war. He was sure that America possessed the economic and moral ability to lead the emerging new system in peace, if Americans could only wake up to their destiny and identify the right way to go about it.

Some of Willkie’s ideas for a US-led future now seem weirdly predictive, though not always in ways he might have preferred. Broadly sympathetic to anti-colonial sentiment in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, he championed economic interdependence as the path toward global peace and prosperity. He wanted independence for peoples colonized by the Europeans, but he also wanted western Europe to forfeit its sovereignty and form a single European state, and for the age of European empires to cede to one of American-led global federalism.

One World came in second on the nonfiction bestseller list for 1943. It may have been America’s fastest selling non-fiction title to that date. The book helped to inspire the pacifist idealism of the World Federalist Movement, which secured the support of Einstein and Gandhi, but Willkie, Zipp admits, ‘did not have a blueprint for a postwar organization’. One World was ‘short on particulars’. Did the shortness of its particulars account for the extent of its appeal?

Willkie, a salesman since early childhood, would have argued that capitalizing on a shared sense of humanity mattered more than technocratic details. He was also not planning on dying. An overweight smoker and drinker, he was toppled by a series of heart attacks and died in October 1944, aged 52. Had he lived, he would have faced the realities of a world divided by the Cold War, and the opposition of business and political interests among his allies. ‘We mean to hold our own,’ Churchill said in response to Willkie’s post-imperial visions. ‘I have not become the King’s First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.’

Willkie’s story as an idealist and media sensation is familiar. Americans fall in love with moral crusaders and then forget them: Al Gore, Greta Thunberg, Bono, Kofi Annan, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. In hope, we prefer flesh and blood to the faceless state. When things get bad, people are easier to dispense with than governments. So we move on, at a rate that would have depressed Willkie to his core.

Belief that global harmony is within our reach is another American habit. It persists in foreign policy on the right as on the left and can be seen every year taking its leisure in Aspen. The legend of Wendell Willkie, global idealist, reflects the public’s desire to believe. ‘Even as Willkie’s own name faded,’ Zipp writes, ‘the idea of “one world” enjoyed a strange career. Willkie’s vision was discarded at the highest levels of diplomacy and statecraft, but it lived on elsewhere.’

Zipp writes that a ‘full history of the idea’s long tail lies beyond the boundaries of this story’. Had he trained his research skills on the history and psychology behind the one-world impulse — where and how it started, why it comes and goes but never quite disappears, how our new digital environment transforms or modifies the impulse — the result might have been a more interesting book and a stronger case for remembering Willkie. These themes are given only a dozen or so suggestive pages in an adumbrated biography that skimps on Willkie’s early life and private life. There is little here about Willkie’s lengthy affair and friendship with Irita Van Doren, the book review editor of the New York Herald Tribune. What did Willkie, who wrote a bestseller, learn from her about the press and the world of ideas?

Though Zipp mourns that ‘so many of the hopes he championed have been discarded’, he argues that Willkie’s ‘diagnosis of the value of global interdependence has never been more prescient’. Though global warming, pandemics and nuclear threats were not Willkie’s concerns, the need for global thinking has risen with the stakes. Willkie’s retrospective significance as a precursor rises along with them.

Zipp’s able and even account rarely intrudes on its subject. He hopes that as the United States reaches the ‘end of its long turn as the great global power’, Willkie’s example ‘may yet offer us undiscovered resources for living in the “one world” he heralded’. Just what these undiscovered resources would look like is unclear. Willkie’s ‘project’ was vague and the global landscape has changed. But Zipp may be on to something here.

Willkie, like the current president, was independently wealthy. He came from the business world and adapted to the political one. He understood the media and how to cause a sensation. He was sensitive to the plight of the downtrodden. He was pro-trade and anti-racist, educated and honest, a down-home American but woke to the world. The public, we must not forget, were susceptible to his one-world universalism and craved his message of world peace. Perhaps this ‘blueprint’ is Wendell’s most enduring legacy.

Willkie caught the zeitgeist by the tail, only to have it slip away. The philosophically inclined and the serious student of American history might not be satisfied by The Idealist. Big thinkers like Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg might, however, want to buy a few copies.

This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.