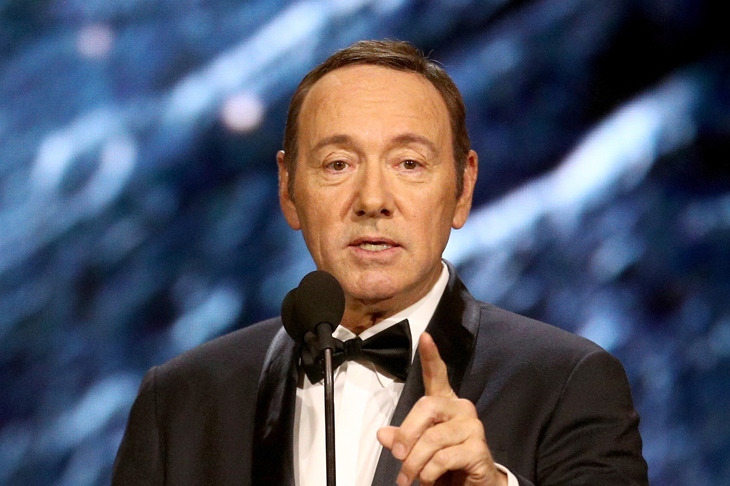

The sixth and final season of House of Cards has begun without Kevin Spacey, who played the murderous Democratic American president Frank Underwood. Netflix fired Spacey when he was accused of multiple sexual assaults last year, although he is not yet charged with any crime. The longed-for dénouement of Frank Underwood — the moment when he realizes his crimes have been in vain — never came. Instead his wife Claire, so lovely in looks, is now president. (It’s TV.) When the trailer for the final season appeared, Underwood was already in his grave, with Claire, played by Robin Wright, standing over it. Wright gave an interview saying that she had never known Kevin Spacey, which made me smile, because it is exactly what Claire would have said.

I don’t write to defend Spacey as a man. I met him once and got the freezing stare he gave to all journalists who sought something of him beyond that which he wished to give. Criminal or not, he was a man with secrets, and I expected, and deserved, nothing else. He didn’t sign autographs at the stage door of the Old Vic, where he was artistic director from 2004 to 2015. Rather he signed them through a slot in the door — and why not? There is something hateful about the way we crawl over actors, looking for a narrative they give better, and more freely, on screen.

But I am angry that he fell without trial. If #MeToo and #TimesUp take away the presumption of innocence, we will be worse off. If Spacey is not tried, and therefore not convicted — a few enquiries have come to nothing, owing to the statute of limitations, but others are ongoing — he should return to acting. But I fear he won’t. Hollywood is filled with hypocrisy, and its sins against beautiful young men and women are so numerous that it must pretend to atone before it offers up the next body.

I was surprised by none of it. It was all there to see in the product. Cinema doesn’t have to be so rotten, but it is. There is profit in exploitation, and I saw it in House of Cards too, when a young woman’s naked body wandered, so pointlessly, across the screen.

But I can defend Spacey the actor and say that he was always fascinating because he was amoral. He can do charm, vulnerability, rage — anything but sincerity. Compare him with today’s rising leading men — they all seem to be called Chris, and they are handsome, like Labradors — and he is all risk. I suppose Benedict Cumberbatch is the closest — his face is similarly awry, his talent as large — but Cumberbatch, you sense, is essentially wholesome. Spacey is not.

He has two Oscars, for The Usual Suspects (1995) and American Beauty (1999), which have yet to be recalled. But there is time. He has a new name, too — his original was Kevin Fowler, and it suits him much better. Spacey, already, sounds like reinvention. Fame came late; he was never handsome, just sensuous and dangerous. If you are glib, he looks like an evil baby that is capable of anything.

His breakthrough roles were the liar — though liar is really too small a word for what Verbal Kint was — in The Usual Suspects, and the dreamer Lester Burnham in American Beauty. He was also an intellectual — and therefore hack — serial killer in Seven (1995), but he did it better than anyone else. When he removed Gwyneth Paltrow’s head, and made Brad Pitt cry, you were glad. Then there was Jack Vincennes in L.A. Confidential (1997), the best film of the 1990s. LA was a corrupt town, and no one was more believably corrupt than Spacey’s cop, who arrested movie stars for drugs offenses and tipped off the press, so that he could be famous. He looked stunned when he died.

His best roles, then, are closest to what we presume he must be. He has never given an interesting interview. He excused himself like this: ‘It’s not that I want to create some bullshit mystique by maintaining a silence about my personal life. It is just that the less you know about me, the easier it is to convince you that I am that character on screen.’ In 20 years, he has given almost no interesting quotations. There is this: ‘I’m attracted to characters in some kind of moral crisis or moral decay.’ And this: ‘I think people just like me evil for some reason. They want me to be a son of a bitch.’

According to his brother — a Rod Stewart impersonator — a violent father did for him, giving him that gift for mimicry, the charm, and the freezing stare. Certainly, the offenses he is accused of — mostly groping, but some much worse — bespeak unease with love. People who like themselves don’t steal intimacy from others. They ask for it. He finally came out as gay when he apologized for the first assault he was accused of — he says he does not remember it — but this was received with fury by the gay community because the accuser was 14 when it apparently occurred. It was considered manipulative, and it was.

When he collected his Oscar for American Beauty he dedicated it ‘To my friends for pointing out my worst qualities. I know you do it because you love me. And that is why I love playing Lester. Because we got to see all of his worst qualities and we still grew to love him. And this movie to me is all about how any single act from any single person, put out of context, is damnable.’

And so I wonder if Spacey is that strange and isolated creature, the risk-taker who longs to be caught. I don’t know where he is; there is no trace of him in any media I can find. But I will miss him. ‘And like that,’ as he said at the end of The Usual Suspects, ‘he’s gone.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.