What’s so serious about a red nose? How should we analyze the ‘specific socio-historical relations’ and ‘aesthetic trends particular to geographic context’ of the circus? How can we ‘codify’ equestrian performance in the ring?

With the publication of The Cambridge Companion to the Circus, this artform has tumbled out of the Big Top and into the library and lecture hall. It’s a recent arrival to lofty, learned spaces. When Vanessa Toulmin of Sheffield University, widely regarded as the world’s leading expert on circus and fairground history, first ventured into academia, she did so under the guise of an ‘early film historian’, as circus wasn’t regarded as worthy of study. Now ‘circademia’ has become a respectable area of research for PhD students, and higher education institutes offer degrees in circus studies. Circus has become serious.

But does all this analysis and examination wash out the sequined sparkle? Can circus’s raw joy, derived from visceral pleasure rather than cerebral contemplation, survive such scholarly scrutiny? Unlike other artforms such as ballet and opera, circus has flourished as an outsider, often sniffed at and looked down upon. If it’s brought inside the mainstream artistic canon, does it lose its immediacy and accessibility? Does it dissolve into no more than physical theater?

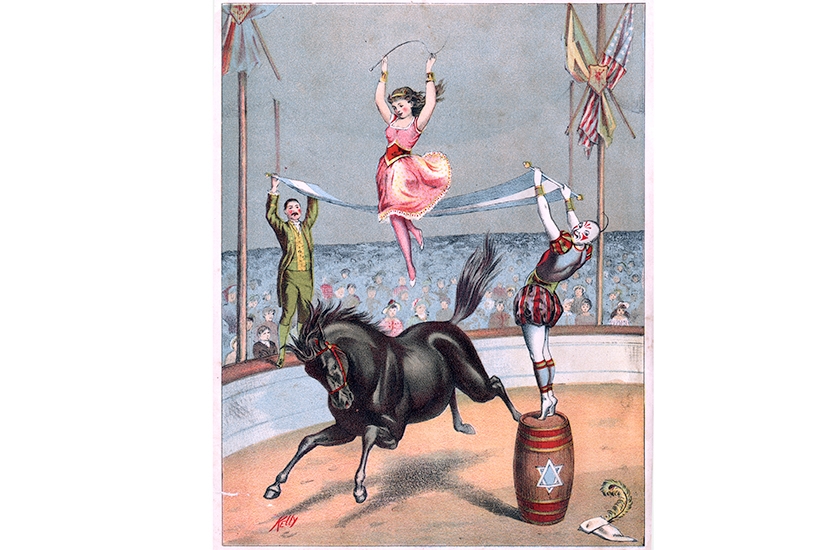

I’m a circus person, so naturally greeted this volume of 16 essays from renowned academics worldwide with glee, but also a little bit of worry. Bringing together much of the circus research that’s been quietly happening in archives over the past decade, it is divided into four parts: the international perspective, circus acts, circus today and circademia. Subjects range from the late 18th century, when Philip and Patty Astley founded the first modern circus, in Lambeth, opposite the Houses of Parliament, to today’s contemporary shows.

It’s not a fully comprehensive history of circus, and the choice of subject matter is somewhat random. There are pieces on American, Czech, Australian and Argentinian circus, but not Indian or Russian. There’s also an eclectic timeline, oddly beginning in 1537 when ‘A rope dancer, performing on the battlements of St Paul’s in London, appears before Edward VI as part of his coronation celebrations’ and ending in 2018, when the French circus-research association Collectif was created, and Circus and Its Others II was crowned the biggest international conference focused on circus and circus arts in Czech history — two events whose significance were new to me. In this magician’s hat of information, when you never know what will be pulled out next, it’s good to see mention of Rebecca Truman’s Skinning the Cat, a pioneering British all-female aerial troupe of the 1980s which challenged the notion that only a man could be a catcher on the trapeze.

Some essays emphasize how quickly circus became embedded in our culture or, as Matthew Wittmann, the curator of the Harvard Theatre Collection in his useful ‘The Origins and Growth of the Modern Circus’ contribution says, became ‘an expansive cultural form’. By the 1820s there wasn’t a major European city without its own circus building, and circus soon became a global phenomenon. It has always been capacious, flexible and adaptive, open to all sorts of ever-changing acts, including female, cross-dressing and black performers. Early 19th-century shows would typically have Italian clowns, a Flemish strongman, and Arab acrobats. In her essay on the Criollo Circus in Argentina, Julieta Infantino of the University of Buenos Aires points out: ‘Long before the new or contemporary circus, the so-called traditional circus incorporated…dances, music and the theater’. From Charles Dickens’s novels to the fashion designer Marc Jacobs and the artist Cindy Sherman in her clown series, circus has inspired new creations. The irony is that while it has been an inspiration to all other art forms for more than 250 years, it hasn’t been properly considered one itself.

There aren’t many laughs in this volume, but there are a few gasps. Alisan Funk of Stockholm University of the Arts opens her chapter on the global rise of youth circus: ‘With its roots in “death-defying” spectacle, circus does not strike the casual observer as an appropriate activity for youth.’

The final section of the book comprises essays about essays about circus studies. Already the discipline is beginning to reflect upon itself. But if that’s what’s necessary for circus be taken seriously, then we should have more of it. I encourage ambitious and innovative PhD students to throw their hats in the circademia ring.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.