When a young singer and pianist named Charles Brown was hired in 1944 to play at Ivie’s Chicken Shack, the legendary jazz singer Ivie Anderson’s nightclub in Los Angeles, he was instructed to play ‘nothing degrading like the blues’. It wasn’t an admonition that he heeded very long. The blues didn’t degrade him. He elevated them.

After Brown died in 1999, Bonnie Raitt, who toured with him starting in 1987, deemed him ‘the most extraordinary piano player I’ve ever heard’, noting that he ‘led the West Coast blues explosion’. Indeed he did. His rhythm & blues hits in the late 1940s included ‘Trouble Blues’ and ‘Merry Christmas, Baby’, and his soulful voice and piano influenced the likes of Fats Domino, Ray Charles, Chuck Berry and Sam Cooke. Decades later, Elvis Costello co-wrote ‘I Wonder How She Knows’ with him.

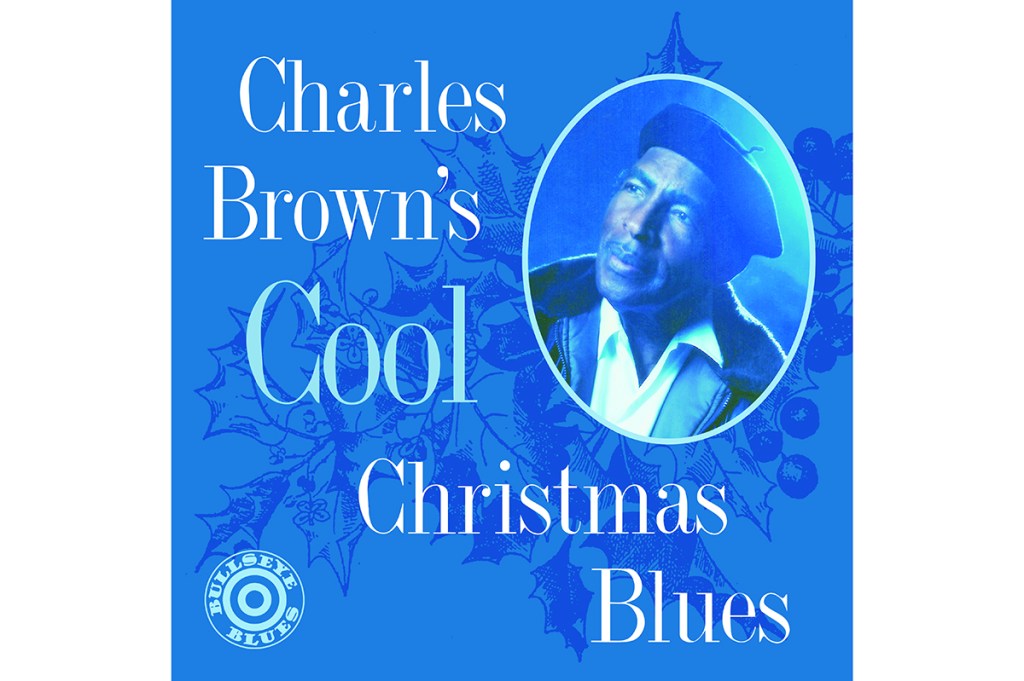

The release by Craft Recordings of Charles Brown’s Cool Christmas, an album recorded in 1994, provides a welcome opportunity to revisit this remarkable bluesman’s musical odyssey. Brown, who was born in 1922 in Texas City, Texas, grew up with a grandmother who insisted that he study classical music as a lad with a dollop of Fats Waller thrown in. This classical background endowed him with a musical grounding that many other musicians simply couldn’t match. He hit the big-time after traveling to Los Angeles, where he won a contest at the Lincoln Theater by playing a concoction that mixed together Earl Hines’s ‘Boogie with the St Louis Blues’ with the Chopin-style movie theme ‘Warsaw Concerto’.

What it actually sounded like one can only wonder. But it clearly wowed the judges and it was good enough to prompt two other African American singers, Johnny Moore (whose brother Oscar played in the Nat ‘King’ Cole Trio) and Eddie Williams, to invite Brown to join them in the Three Blazers. In 1945, Brown sang the lead on their biggest hit, ‘Drifting Blues’, but it was a rocky tenure. When Nat Cole broke up his trio, the group became Oscar Moore’s backing band, and ‘Drifting Blues’ was released under Moore’s name only. Brown’s first album under his own name, issued in 1949, was titled Get Yourself Another Fool.

Once rock ’n’ roll arrived in the mid 1950s, Brown’s songs were recorded by Elvis, Sam Cooke and other stars, but his own career faded. For a while he was stuck in Newport, Kentucky working for a mob boss who greeted his musing about a return to the West Coast with the remark, ‘Charles, you’re pretty and I love you, but you wouldn’t look too good with a bullet in your brain.’

Eventually, he got out. On the 1962 live album Drifting Blues, the singer once tipped as the next Nat ‘King’ Cole sounds closer to Ray Charles. But Brown, like not a few jazz greats, found himself living in reduced circumstances as musical fashions changed, until he was performing odd jobs such as washing windows for a chum’s janitorial service in LA. It was Bonnie Raitt who rescued him.

‘Going out on tour with Bonnie Raitt really helped me because she saw the goodness in me, in what I was about,’ Brown told the Los Angeles Times in 1995. ‘Before she was born, I was out there, being a No. 1 artist across the country… I’m stronger now than I was even then.’

It shows on the Craft reissue. Brown, as this album amply demonstrates, had not lost a step. Instead, he rose to the challenge with gusto, demonstrating that he remains a consummately refined performer who infuses his lyrics with his laconic drawl. With his training in classical music, there was never going to be anything rough or rebarbative about his playing. Quite the contrary. There is a wonderfully relaxed ease to his singing, a plangent undertone coupled to an insinuating confidence that carries along the listener in its path. Indeed, the holiday season, as this album makes clear, seemed to bring out the best in him. This album includes such delectations as ‘Santa’s Blues’ and ‘Please Come Home for Christmas’. These are simple tunes, but they do not sound simplistic when sung by Brown.

Craft has itself certainly gone all-out to honor Brown’s legacy. This pressing not only marks the first vinyl release of the blues titan’s 1994 Christmas album, which was nominated for a Grammy, but it is also available online in an exclusive white and blue marble vinyl variant that is limited to 350 copies.

If there is anything to whet a collector’s whistle, it is the nifty limited editions that various purveyors of vinyl have been offering over the past decade or so. At this point, given the numerous articles about the comeback of vinyl, it almost seems otiose to point to the sonic advantages — immediacy, warmth, fidelity to the original sound and so on — of an effort such as Craft’s. This album, friends, is lit. As Brown himself sings, ‘I’m all lit up, all lit up — like a Christmas tree!’ Yes, he was.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2020 US edition.