“A sad tale’s best for winter,” says little Mamillius in The Winter’s Tale: “I have one/ Of sprites and goblins…” (He is dead by Act III.)

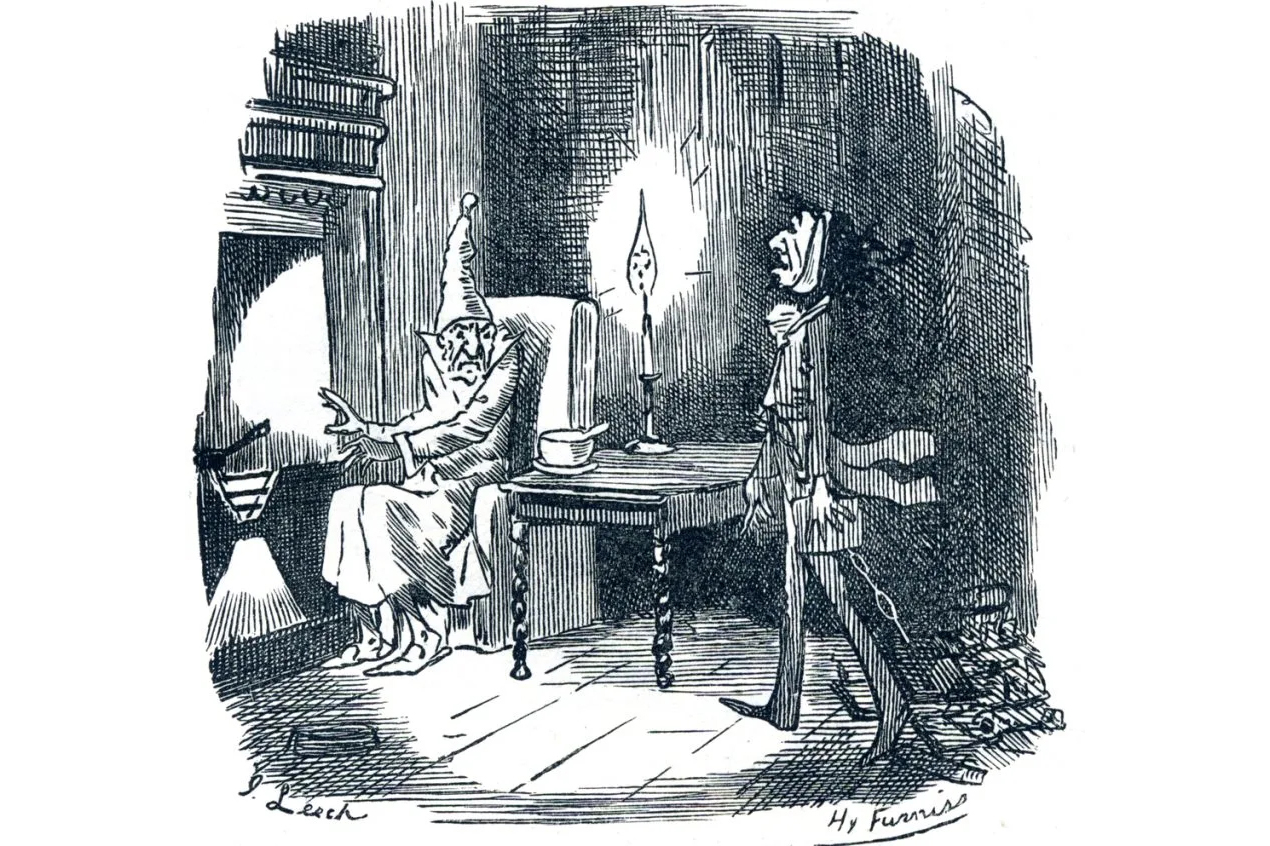

Ghost stories have always been best told on a midwinter night — preferably aloud, in a group drawn close together around a blazing fire. Pleasure comes from awareness of the icy cold and dark, hemming our small convivial light: there is a particular frisson in the contrast between “in here” and “out there,” between the snug “us” and a possibly malign “them,” the known and the unknown. And Christmas Eve, traditionally, was the time to swap ghost stories — drawing upon the early Christian notion that spirits and demons had a peculiar freedom on the night before an especially holy day. Halloween, the night before All Hallows or All Saints day, has now usurped this license; but in Victorian times, as Jerome K. Jerome remarked: “The average orthodox ghost does his one turn a year, on Christmas Eve, and is satisfied.”

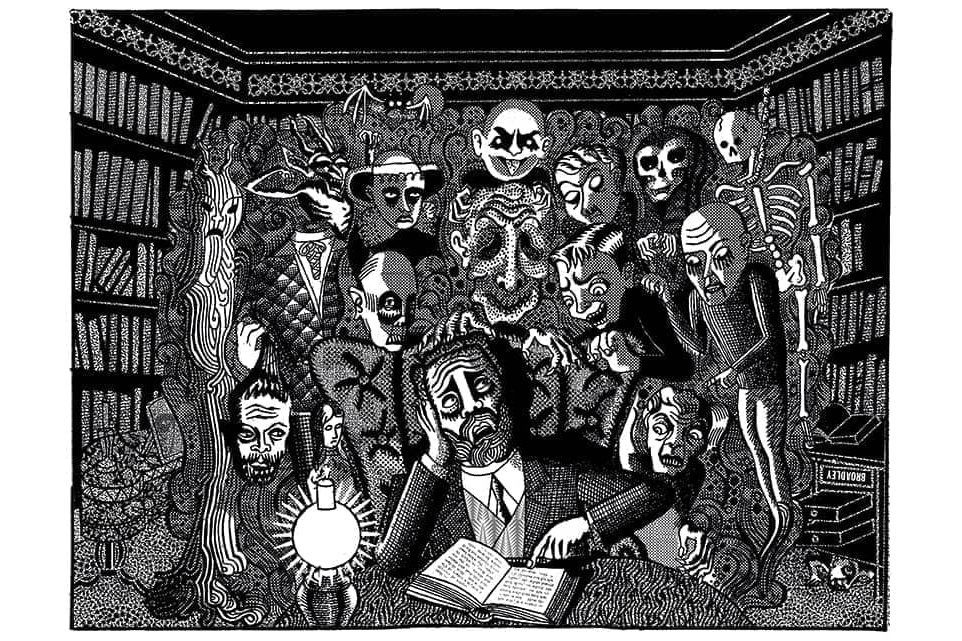

The oral tradition of telling ghost-tales at Christmas had become literary “orthodoxy” in Victorian times — thanks to Charles Dickens, and to the extraordinary proliferation of periodicals in the nineteenth century. Many of these imitated Household Words in producing a special, ghost-filled Christmas issue. The genre rapidly spawned clichés. Many of the innumerable stories in the back numbers of these magazines are the Victorian equivalent of Christmas “repeats” on television. And the feeling of familiarity is not helped by the fact that so many ghost stories are themselves tales of ghostly re-enactments — repeats of repeats, as it were. If a murderous event is supposed to recur year after year it can lack tension, which has to be whipped up by lashings of Gothic melodrama. Luminous skulls, chains, dripping daggers, shrieks, haunted organs, hidden chambers and monk’s habits are stock in trade; lost wills, buried treasure and unburied corpses prey upon the minds of the departed.

Most ghosts haunt ancient houses, and prefer to appear to guests (though Ancestral Curses and Banshees snobbishly stick to titled landowners and their heirs): guests who are given a bedroom in the West Wing, or the Yellow Chamber, may be Unsuspecting, in which case they often do not at first realize that the ghost is a ghost at all, or Skeptical, in which case they deserve to be dosed with something much, much nastier. Side effects include Marie Antoinette syndrome, palsy, madness and death.

In an overcrowded market, originality became difficult. In “Thurlow’s Christmas Story,” by John Kendrick Bangs, the narrator has a deadline looming to provide a Christmas story for the Idler: the psychological darkness from which his supernatural visitations come is writer’s block. As the narrator says, attempting to spur himself on, most Christmas stories provided were neither original nor even especially Christmassy — “…the usual ghostly tale,” merely “with a dash of Christmas flavor thrown in here and there.”

There are stories, however, in which Christmas is central to the atmosphere — and some writers, too, who rise above snug cliché and re-invent the ghost story to make us realize that the darkness may, after all, not be “out there,” but within us.

Christmas provides good starting points for horror. There is the weather. There is snow, of course, cutting off all communications; fingering the windowpanes… “I am afraid we shall have a terrible winter” can be said ‘in a strange kind of meaning way’ (Mrs Gaskell: Old Nurse’s Story). In the first half of the nineteenth century, England was in the throes of a mini ice-age, and for the first eight years of Dickens’s life there was a white Christmas every year. By 1891, however, Jerome K. Jerome describes the typical Christmas Eve as “dismal” — “cold, muddy and wet.” In Algernon Blackwood’s terrifying story “The Kit-Bag” (1908), the narrator is packing on Christmas Eve to escape from the “sleety rain.” His surroundings are now not an ancient mansion but an old house subdivided into “cheerless” lodgings; and he is attempting to escape to real Christmas snow, for a skiing holiday. But first he has to pack… Blackwood is a master at building the tension.

“It is difficult to say exactly at what point fear begins… Impressions gather on the surface of the mind, film by film, as ice gathers upon the surface of still water…”

Disconcertingly un-Christmassy weather features in E.F. Benson’s story “Between the Lights” (1912). On a conventionally snowy Christmas Eve, when “hackneyed” ghost stories are being told, one guest tells of his experiences the year before, when it was so warm and sunny on the day before Christmas that the guests played croquet on the lawn. The fear “out there” in this tale is not climate change — that horror was yet to be invented— but something fetid and primordial.

Seasonal Christmas games can also lend themselves to the genre of fear. For a child, hide and seek is always edged with terror. Though there is no ghost in it, the ballad of “The Mistletoe Bough” was morbidly popular in Victorian times: a bride, married on Christmas Day, hides for a game in an old oak chest. Her skeleton is discovered years later. (Christmas weddings were popular in Victorian times: for the modern woman, the idea of organizing both simultaneously is itself horrific.) A Christmas house party, and a game of hide-and-seek in a rambling country house, with the lights turned off, is the setting for a classic old-fashioned ghost story, “Smee” by A.M. Burrage: the title is the name of the game, where players call out — or not — a corruption of “It’s me.”

Equally, anyone who remembers their own very early childhood will remember being frightened by a toy, probably given by a (well-intentioned?) uncle. Dickens, of course, has perfect recall. In “A Christmas Tree” he describes “that infernal snuff-box, out of which there sprang a demoniacal Counsellor in a black gown, with an obnoxious head of hair, and a red cloth mouth, wide open, who was not to be endured on any terms.” An early tale of haunted toys (1859) is “The Wondersmith,” by Fitz-James O’Brien, in which an army of tiny wooden dolls are animated by evil spirits, and armed with poison to kill “Christian” children on Christmas Day. Unfortunately, the “us” and “them” in this story is unpleasantly racist: the masterminds are evil “gipsies.”

Haunted doll houses are nowadays two-a-penny; but I can think of only one haunted Nativity set, in Jeanette Winterson’s “Dark Christmas” — though it is the sound of a marble being rolled on a wooden floor in the attic above which is truly horrifying.

M.R. James may have told his stories at Christmas, to a small audience of his academic colleagues and King’s College choristers (did he acknowledge any dark resemblance between himself and Mr Karswell in “Casting the Runes,” who terrified local children with a winter slide-show featuring “a horrible hopping creature in white?”) but only one of his stories has a Christmas setting — and marionettes as childishly horrible as Dickens’s Jack-in-the-Box. “The Story of a Disappearance and an Appearance” features a missing clergyman, and a demonic Punch and Judy Show.

Another uncanny Christmas show is central to “Visiting Star” by Robert Aickman. Aickman’s extraordinary stories are rarely ghost stories, exactly. He preferred to call them “strange tales”: they have the oddly detailed lucidity and surreal, pervasive unease of a bad dream.

It was Aickman who remarked that “the true ghost story is akin to poetry.” This is exemplified by one of the very best ghost stories ever written, “The Open Door” by Mrs Oliphant (not to be confused with another ghost story with the same name, published in the same year, 1882, by Charlotte Riddell). Mrs Oliphant’s is not strictly a Christmas ghost; but it is undoubtedly a wintery “sad tale”: a voice in the cold dark, crying heartbreakingly at a ruined door: “Oh mother, let me in! Oh, mother, let me in!”

The story is hauntingly powerful because it comes from “perilous stuff” within. By the time Mrs Oliphant wrote this story, she was a widow, who had lost two children in infancy, and a beloved daughter aged eleven. She was supporting not only her own surviving children, but two bankrupt brothers — one of them a widower with three children, one an alcoholic — and an orphaned cousin. Surrounded by feckless men, she saw her own sons growing up sickly and dependent… In this story, Oliphant summons up the dark emotions which cannot be allowed into her conscious mind: black loss, longing and despair at the death of her child, which are incompatible both with her Christian faith, and with the need to keep on going; and her agonized helplessness, even guilt, at not being able to “be there” for her daughter on the threshold of death.

And there is another layer of unmentionable feeling: in another of her stories, “New Year’s Day,” the underlying guilt is of parental failure in the upbringing of her sons — and the ghost in this story was, in its past life, like her own boys, weak and easily “led away.”

Ghosts, it is often said, return because of “unfinished business”: it is the “unfinished business” within a writer’s soul that creates the truest poetic ghost stories.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.