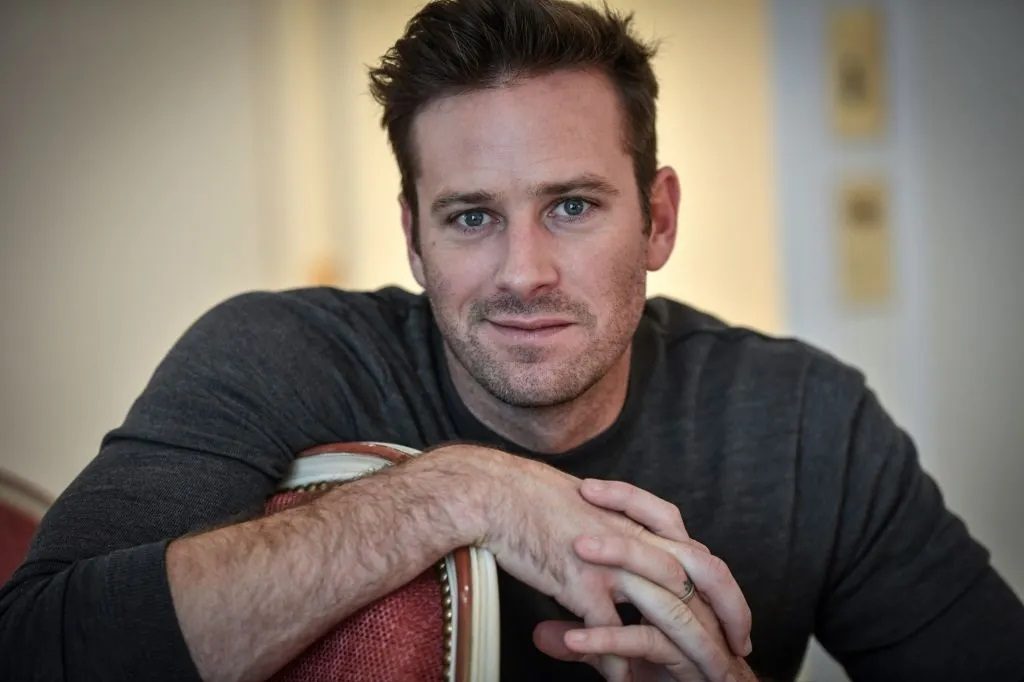

Sam Harris has been in several tangles in his busy career. This is to be expected from a leader of the New Atheist movement, a vocal critic of Islam (he called the term ‘Islamophobia’ a ‘pernicious meme’), a member of the Men’s Movement (shocker: some non-men found it anti-woman), and a gleeful saboteur of the notion of free will. But for years now, Harris has been using his background in neuroscience and meditation to help people untangle their minds through his podcast Making Sense.

It’s hard to find a podcast about meditation that is not made by or for quasi-spiritual, anti-vaxxer yoga moms. Making Sense is for the more serious inquiring mind. Harris, dry and wry, discusses not only meditation but philosophy, science, politics and ethics. The podcast can help you stay grounded after a pandemic year when our minds have wandered far wider than our physical selves. Perhaps we have never needed meditation more.

An episode titled ‘Knowing the Mind’ features the neurologist Steven Laureys extolling the medical uses of meditation. In fact, Laureys says he has prescribed meditation as a substitute for general anesthesia during thousands of surgeries. We do not, of course, hear from the un-anesthetized.

Meditation isn’t just for numbing you while someone makes an incision in your peritoneum. Harris began practicing meditation at 18 after taking MDMA, better known as Ecstasy. He’s advocated psychedelic and euphoric drugs as a ‘gateway towards self-inquiry’. Meditation strengthens focus and self-control, Harris says, and has even helped him overcome the ‘subject-object illusion’, which is ‘the primary illusion that meditation is designed to cut through’.

The real enemy of self-enquiry, he says, is distraction. In a conversation with neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley, Harris discusses how dangerous a wandering mind can be. Harris hates social media.

‘With social media we’ve all been enrolled in a psychological experiment for which no one gave consent…All communication has become performative, and on the most important topics, it now seems to be fury and sanctimony and bad faith, almost all the time. We appear to be driving ourselves crazy… as in incapable of coming in contact with reality. Unable to distinguish fact from fiction. And then becoming totally destabilized by our own powers of imagination.’

I’m guessing he was looking at comments from some of his 1.4 million Twitter followers. Information helps us survive but our brains lack the capacity to process unlimited information. ‘If the system is overloaded,’ Gazzaley tells Harris, ‘there will be consequences.’ The price of constant internal and external distractions is not just lost time and opportunities.

‘There’s an emotional cost to all of this,’ Harris says. The frenetic escape from boredom only breeds more boredom. It appears that we possess endless resources to mitigate boredom, but the need for immediate reward that tech has impressed on our brains only invites more boredom. For all its charms —‘access to the totality of human knowledge’, for one — digital connectivity is ‘clearly fragmenting our lives… rewiring our brains into different expectations of reward, different habit patterns’. Meditation helps you ‘step off the hamster wheel’ of endless distraction, Harris says, and may cure our epidemic of depression.

A sworn enemy of organized religion, Harris wants to strip meditation of any religious context. Fortunately, he claims, Buddhist meditation is ‘perfectly designed for export into the secular context’, like a take-out dinner of the soul: ‘There is a central strand there that is empirical that doesn’t presuppose any religiosity or doctrines that need to be accepted on faith.’ Buddhists, Hindus, Taoists and Sufis will disagree, with varying degrees of courtesy.

Harris ignores the prerequisites for meditation that nearly all religions consider essential. Both Hinduism and Buddhism require of the wannabe mystic a mastery of rules of conduct, from seemingly trivial matters like proper seating, posture and breathing techniques to moral and ethical teachings. Meditation may appear to be a one-size-fits-all means to self-control and mindfulness, but without knowledge, let alone mastery, the newbie will likely find himself running contrary to its spirit.

When I began yoga and meditation, I suspected I would be getting a washed-down western version of a millennia-old practice rooted in the world’s oldest religion. I was pleasantly surprised. The studio owners attempted to provide some semblance of meditation’s Hindu and Buddhist roots with chants and breathing exercises. Then I saw the ‘altar’: as a centerpiece, the owners had placed photos of themselves next to a statue of Ganesh and the Buddha (two different religions), like a souvenir from Disney World.

Harris’s approach to meditation is similar — playing out a form of ‘secular spirituality’ ironically molded from an organized religion stripped of any idea he doesn’t like. Still, Harris offers a peek into some of the philosophy of meditation. But if you want to go deeper, you’ll have to go elsewhere, including into yourself.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.