The law doth punish man or woman

That steals the goose from off the common

But lets the greater felon loose

Who steals the common from the goose

The authors of a fascinating new look at the patchwork chaos called copyright begin their book — Who Owns This Sentence? A History of Copyrights and Wrongs — with this epigraph from an ancient English protest song against fencing, and thereby privatizing, common land. David Bellos, a comparative literature professor at Princeton University and winner of the first International Booker Prize in 2005 for his translations of Ismail Kadare, and Alexandre Montagu, a lawyer specializing in intellectual property and new media law, have written a timely history of a “relatively simple idea — that authors have rights in the works they create.” Not just authors, but artists in many media, scientists, mathematicians and every one of us with our unique individual faces (which may now, in Guernsey, be registered as an intellectual property right as a “personality,” but only, appropriately enough, if you go there in person) should read this book. You will be pleasantly surprised that the authors are on your side.

The concept of copyright — that the creator of an original work has the right for a legally determined period of time to distribute, perform or display same — is a relatively new one, arising in Europe in the Renaissance in conjunction with the advent of the printing press. Plagiarism is far older. With its linguistic roots in the Latin for kidnapper, seducer or looter, plagiarism has vexed authors since Martial complained of the slimy Fidentinus copying his work. Notably, what annoyed Martial most was a loss of sales: Si mea vis dici, gratis tibi carmina mittam /si dici tua vis hoc eme, ne mea sint (“If you’ll willingly call [the poems] mine, I’ll send you them for free / If you want them called yours, then buy this one, so they’re not mine”). Martial and Fidentinus were contemporaries. Is it plagiarism if you were, say, an Elizabethan playwright borrowing from Greek and Roman dramas and the ancient stories in history books, with all changed utterly by your own art? Originality is slippery. There will always be someone there to complain you’re an “upstart crow, beautified with our feathers.”

Originality is slippery. Someone will always complain you’re an ‘upstart crow, beautified with our feathers’

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]

Though the authors discuss the rise of copyright in France and China, among other countries, their focus is on England and the United States. It seemed so simple at the beginning: “Copyright arose in London in the early eighteenth century. In its first form, it gave the authors of books and their assignees a short-term monopoly on the printing and selling of their works.” How in the world did we come to the current pass of conglomerate publishing houses and not authors profiting from books, to a huge corporation buying Bruce Springsteen’s song catalogue for hundreds of millions, “seeking to sequester a source of rent?” Why is the length of copyright so mutable? “Why should Donald Duck belong exclusively to Disney for nearly a century but a miracle cure belong to the company that developed it for twenty years at most?” Bellos and Montagu don’t always answer the questions they raise, but the story they tell of “copyright creep” and an increasing internet-based insistence that if it’s online it’s free to use is both engaging and eyebrow-raising.

From the 1710 Statute of Anne to the Berne Convention of 1886 and US copyright acts of 1976 and 1998, the codification of copyright has served to expand and extend, not to limit it. Who profits from this? Just guess. A system meant to provide for creators and their immediate heirs — a grieving spouse and orphans — for a brief post-mortem term now gives big businesses with large stables of corporate lawyers decades of rights to cartoon animals, performances of “Happy Birthday to You,” colorful circus posters, and Béla Lugosi in a cape and fangs. It is remarkable to me how successful the Motion Picture Association of America and the Recording Industry Association of America have been at retaining, and protecting from entry into the public domain, copyrights, trademarks and even mutably defined publicity rights.

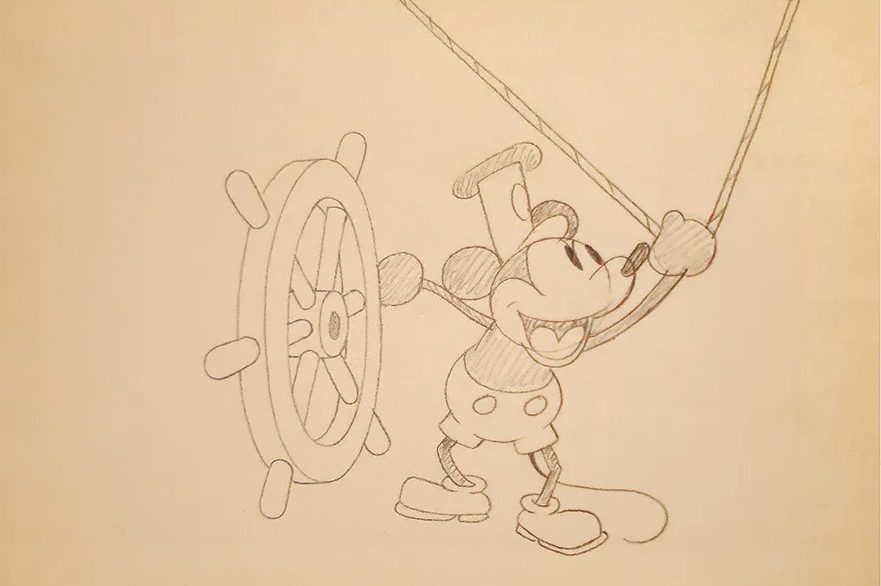

Creative property has never been given the same rights as other property such as “money, houses, land or private jets.” With an increasing amount of creative property now in the hands not of individual begetters but corporate purchasers and investors, Bellos and Montagu warn that this pattern will limit future literary and artistic endeavors. Want to write or paint a parody or imitation? The doctrine of fair use may protect you, but you might have to weather an expensive lawsuit all the same. Even when a book, movie or song is out of copyright, like the recently freed primitive version of Mickey Mouse from Steamboat Willie, beware. Disney still owns the later, cuddlier, round-eyed and -eared versions of Mickey, and the trademark on the logo image of the Mouse himself. Don’t cross the line.

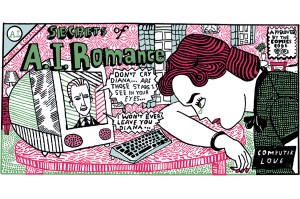

Back in 1998, the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act set out to make the internet a more open place for creation and control infringement. The former, and far less the latter, ensued. Now we have AI, ChatGPT and an exploding copyright arena in which all bets seem to be off. The New York Times has sued OpenAI for copyright infringement in regurgitating its articles; and the Authors Guild have also sued OpenAI “to protect the literary landscape and the profession of writing,” according to the Authors Guild president, Maya Shanbhag Lang. Bill Lee, the governor of the state of Tennessee, announced a new bill last month to update Tennessee’s Protection of Personal Rights law to include protections from AI misuse for the voices of recording artists living and dead. The Ensuring Likeness Voice and Image Security Act is entitled so that its acronym bears the name of Tennessee’s most imitated yet utterly unique performer. Bellos and r will surely approve of, and support, the ELVIS Act.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]

Leave a Reply