A Google search for “Danny Lyon” produces more than 8 million results, yet the celebrated American photojournalist and filmmaker is little known around the world. This superb, quixotic, bare-all memoir ought to change that. Starting in 1962, Lyon not only photographed the heroes of the US civil rights movement as staff photographer for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”), but was, in a way, one of the heroes himself, risking jail, beatings and abuse.

He’s had prizes galore and two solo shows at the Art Institute of Chicago. In 2016 he had a major retrospective in San Francisco and at the Whitney; and a big show last year at the Albuquerque Museum, near the adobe house in New Mexico he built for himself with the help of a Mexican laborer who became a friend.

Danny Lyon and I were classmates at the University of Chicago, along with Bernie Sanders, a good mate of Danny’s whom I didn’t know at all, and of whose youthful Trotskyist politics my own New Left friends disapproved. My contact with Danny was confined to our first year when I had a plausible fake ID that allowed me to buy the beer for our drinking sessions with his biker friend, Frank Jenner, a fellow undergraduate and one of Danny’s subjects.

In 1962, Lyon hitchhiked to Cairo, Illinois, where he was inspired by John Lewis, the chairman of SNCC. Lewis, who was Lyon’s roommate for a couple of years, became a congressman from 1987 until his death in 2020. Lyon writes:

For the next year or so, I would have SNCC to myself as a photographer. Across the Black Belt of the South, the great-grandchildren of enslaved people were rising up to destroy Jim Crow.

In September he made his second trip south to Jackson, Mississippi, with a ticket bought with a donation from Harry Belafonte. Now with a brief to document the civil rights movement, Lyon (who is white) was beckoned inside the police station as he passed, and told by a policeman that an ordinance required anyone “engaged in the business of photography” to post a bond of $1,000:

“That’s for a studio,” I said. “I’m not running a studio.”

He didn’t care. Then I asked if he would take a check, which I meant as a joke. Outside, the policeman who had motioned me in was waiting. He didn’t think anything about me was funny.

[A SNCC worker] had prepared me for this moment; he’d told me to just say I was black, and that I had a black grandmother. The policeman was clearly agitated. “You have to understand we don’t mix the races down here.”

I looked right at him, “As a matter of fact my grandfather was black.”

He said he was going to kill me right there on the spot.

“Here in the parking lot?” I said.

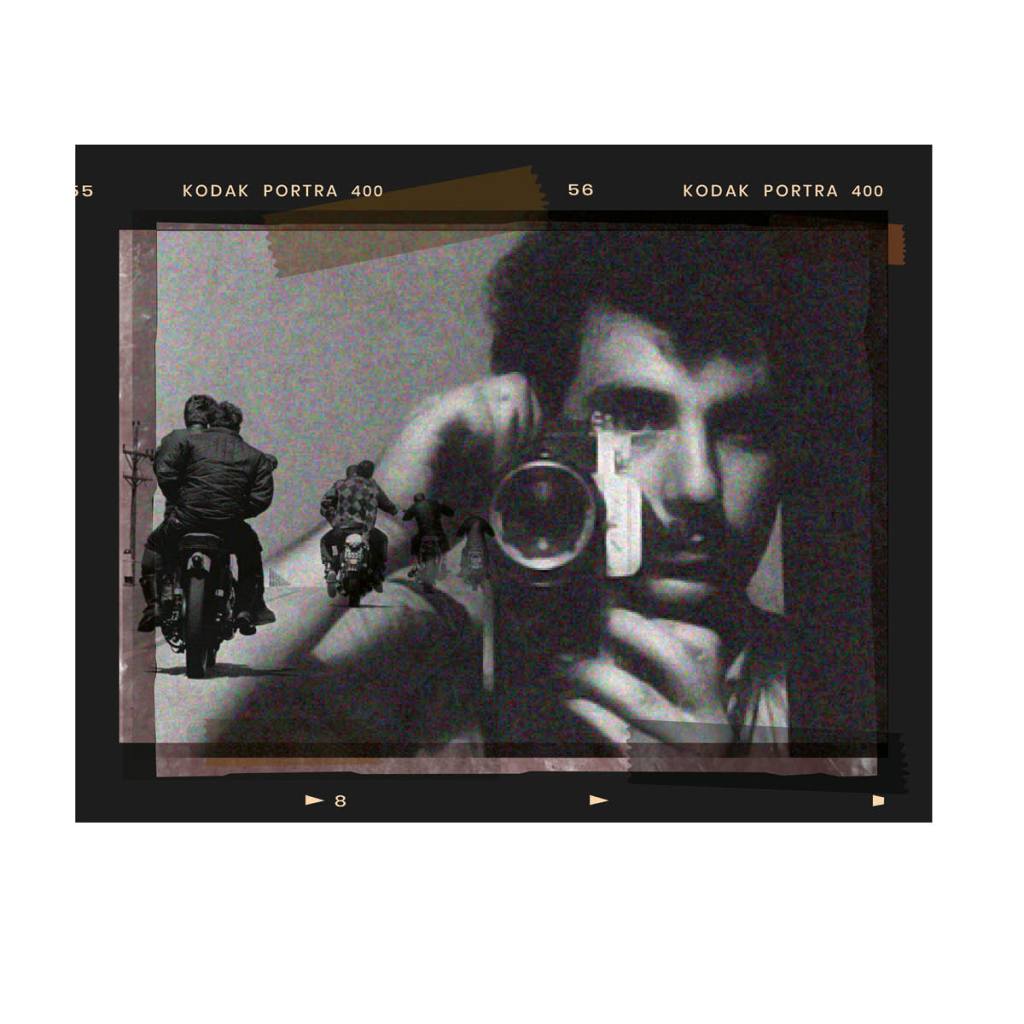

Back in Chicago, Lyon spent his “senior year riding around on my Triumph,” photographing biker members of the Chicago Outlaws and relishing his work in the darkroom. Hugh Edwards, a curator at the Art Institute, instantly recognized the aesthetic merit of his pictures and suggested making a book of them. It turned into 1968’s The Bikeriders.

Throughout his career, including as a sometime photojournalist with Magnum, Lyon has been torn between thinking of himself as an artist and as a journalist. He’s worked in prisons, made pictures of murderers (one of whom his court testimony saved from the electric chair), of homeless, hungry children in Mexico, of hippies in communes, of The Destruction of Lower Manhattan (1969), of Native Americans, of men picking cotton, of the 1986 revolution in Haiti, and several films. At first he disliked the idea that he was doing any of this because of the pay, and his books and film confirmed to him his status as an artist, as did Guggenheim and Rockefeller fellowships. But then he also won the Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism. Previous recipients include Winston Churchill and Walter Cronkite.

For some time Lyon lived in New York with his friend and mentor, the great photographer Robert Frank, and rubbed shoulders with Norman Mailer, Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Paul Butterfield, Yoko Ono, John Lennon — and Cassius Clay (whom he photographed for Magnum and the Sunday Times of London). With his passion for cars and motorbikes, he was a gearhead in every sense. Drugs abounded in his downtown life: “I was taking cocaine up the nose every day — part of me was yearning to leave New York.”

Off he went to New Mexico, where he married a girlfriend, Stephanie. “What did you do that for?” asked Jenner. Two children later, the marriage broke down. After that he married Nancy, had two more children, lived for a bit in the Hudson Valley and elsewhere in the East before going back to New Mexico. Reflecting on his early friendships and adventures, he writes: “We were ‘soldiers in the army’… And we were in love with each other. We were all so young.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply