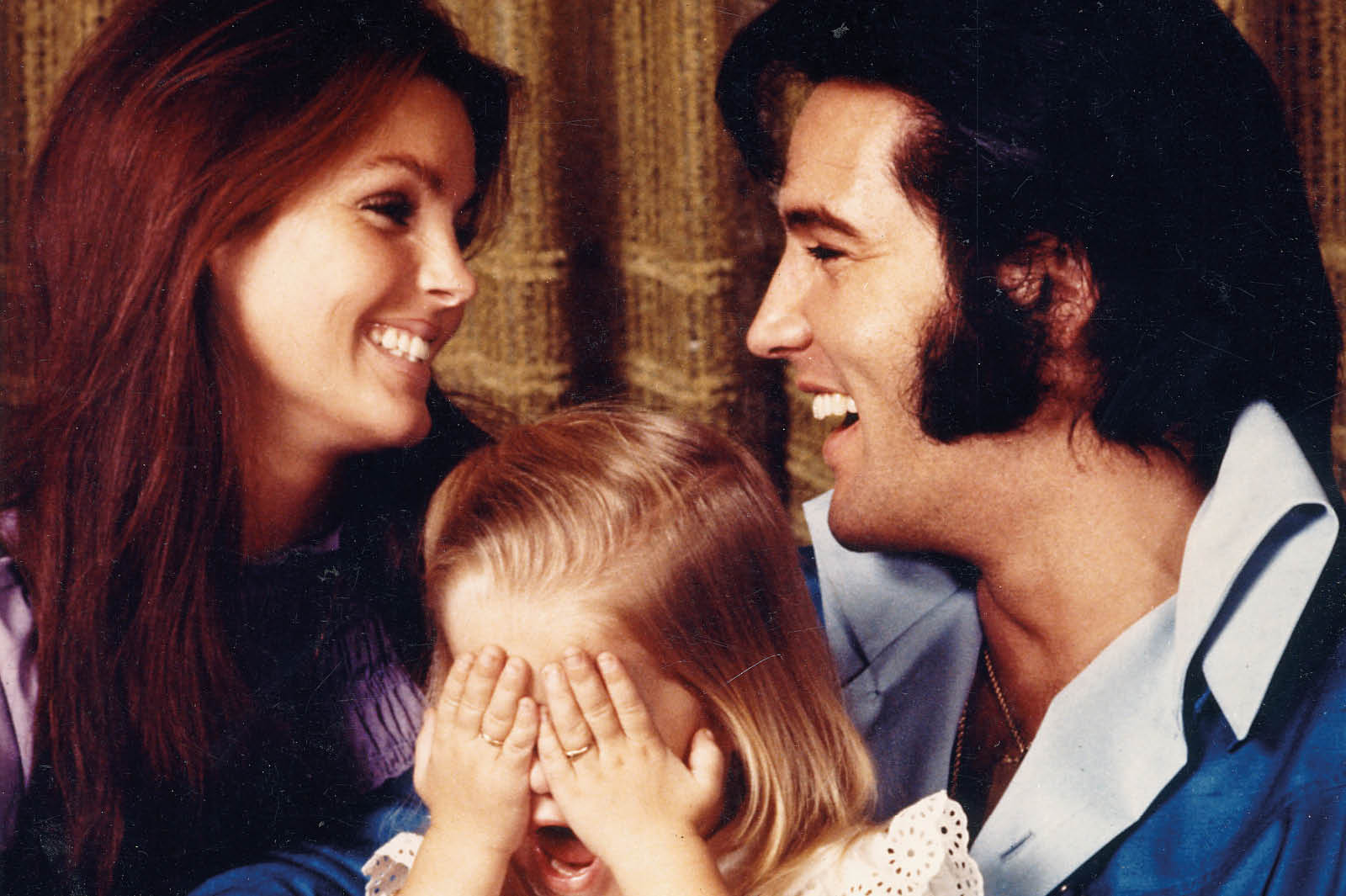

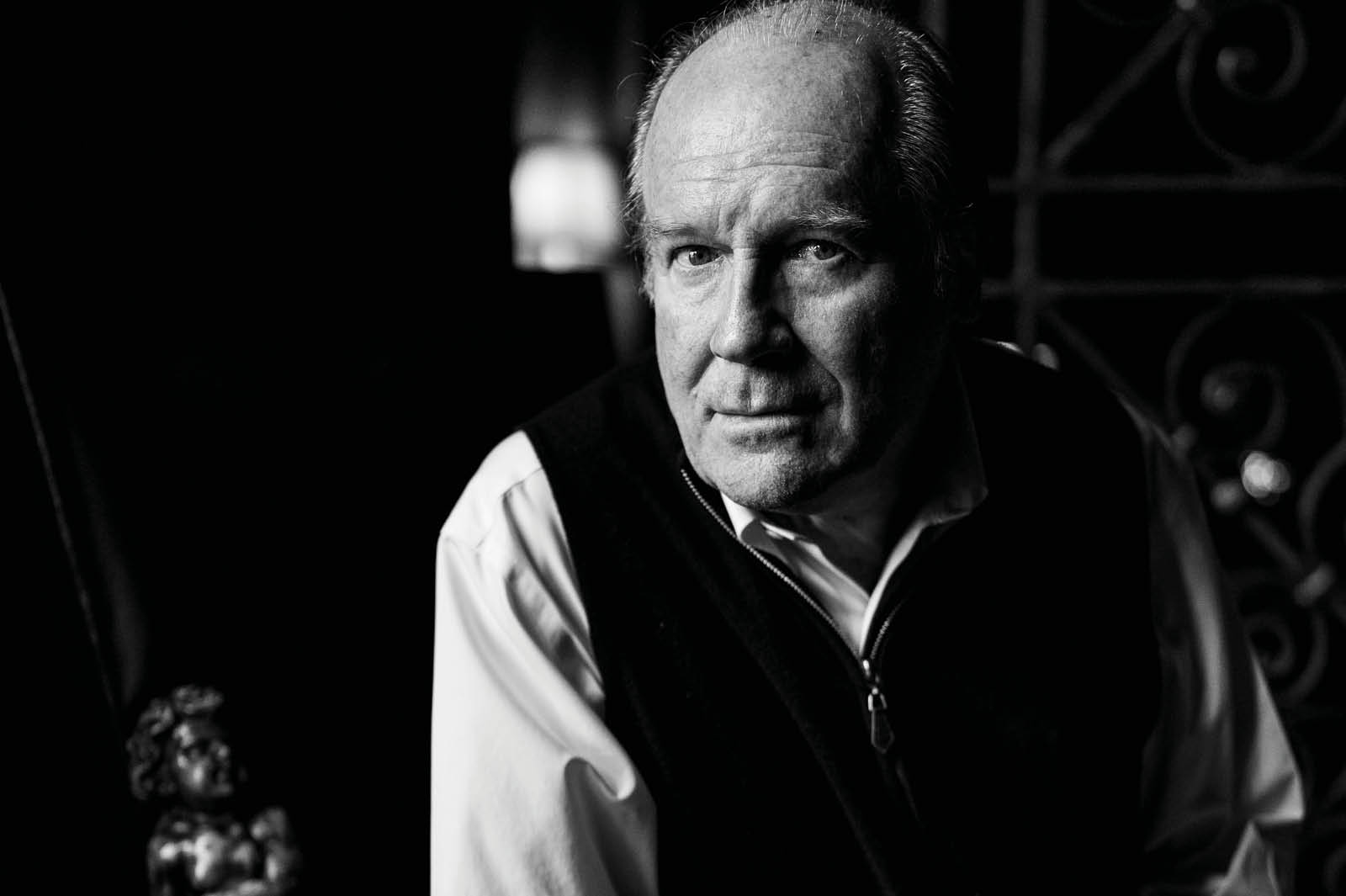

Ten years ago, David Graeber was a leading figure of the Occupy Wall Street movement. He and his fellow protesters camped out in Zuccotti Park, storing $800,000 of donations in trash bags because they didn’t believe in banks.

The anthropologist and anarchist activist called this an experiment in “post-bureaucratic living.” But such politics made Graeber persona non grata at US universities, so he moved to Britain where, in 2013, he became a full professor at the London School of Economics. There, until his death last year aged fifty-nine, he imagined anarchist utopias and indicted what he took to be an oxymoron: western civilization.

In Debt: The First 5,000 Years he called for a biblical-style “jubilee” — wiping out sovereign and consumer debts — which made him popular with his students. In Bullshit Jobs he complained that most white-collar jobs were meaningless and that technological advances had led to people working more, not less. In The Utopia of Rules he noted that, instead of finding a cure for cancer, the most dramatic recent medical breakthroughs have been drugs such as Ritalin, Zoloft and Prozac that serve to ensure that “these new professional demands don’t drive us completely, dysfunctionally crazy.” In a better society, he told me, technological innovation would have focused on enabling us to fly with jet packs rather than holding us down with meds.

Now comes The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, an enjoyable rant of 700-odd pages that Graeber and the University of London archaeology professor David Wengrow spent ten years writing. It opposes what might be called the Private Frazer theory of human history, whereby we’re doomed to live in unequal societies, doing jobs that demean us, all the while rapaciously exploiting nature and each other. That philosophy was set out most clearly, they suppose, by Yuval Noah Harari in his 2014 bestseller Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. “There is no way out of the imagined order,” Harari wrote. “When we break down our prison walls and run towards freedom we are in fact running into the more spacious exercise yard of a bigger prison.”

The Private Frazer theory, the authors suggest, arose when Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued not just that man is born free but everywhere is in chains. Farming chained us to the land and made private property normal; factory labor tightened the screws; now we are stuck in a system that, we supposed, by means of food surpluses and consumer goods, would deliver civilization.

Equally silly, they think, is Thomas Hobbes’s rival account, whereby without the social contract’s curtailing of human freedom, life would be, like Vladimir Putin, nasty, brutish and short. For Graeber and Wengrow though, Rousseau and Hobbes were not describing humanity’s history but telling fairy stories about it. And yet their myths underpin our supposedly rational, post-mythological, Enlightenment societies. Without taming our baser instincts and sacrificing primal freedoms, so the fairytale runs, we would still be hunter-gatherers in loincloths in what the authors call bands that were “basically ape-like in character.” The eighteenth-century French economist Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Baron de l’Aulne, devised a four-stage ladder of economic evolution: foraging was followed by pastoralism, then farming, and finally modern urban commercial societies. Those who remain stuck on the barbarous lower rungs are history’s losers.

Nonsense, argue Graeber and Wengrow. It’s us moderns who are stuck. They turn back the clock 30,000 years to the Ice Age and roll humanity’s history forwards again to explode these myths. Consider the Neolithic Çatalhöyük who lived in what is now southern Anatolia. They farmed cereals, sheep and goats but refused to domesticate cattle or pigs so as not to forgo the social prestige that comes with hunting. That is to say, they chose not to demean themselves entirely by farming but mixed and matched to suit their lifestyles.

Similarly, the folk who built Stonehenge, the authors contend, abandoned continental-style farming 3,300 years ago in favor of a proto-Brexit idyll of collecting hazelnuts as their staple food. They could have farmed but, honestly, it seemed like a grind. Then there were Californian peoples who, depending on the season, would do a little farming or a little hunting and, what’s more, change social structures accordingly (the chief before whom his people abased themselves during plowing became an equal on the hunt).

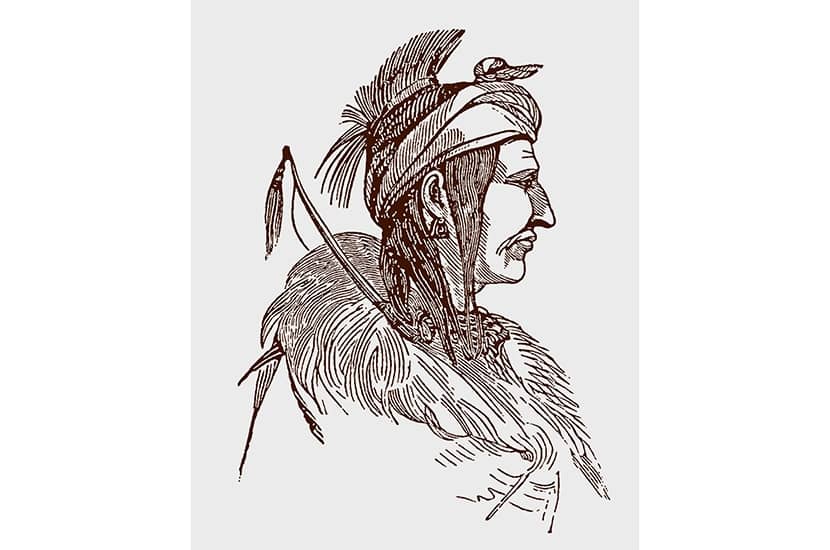

The point is that these supposed primitives were able to create desirable societies rather than be stuck on an evolutionary societal treadmill. No wonder when Europeans arrived in America they were seen as slaves and barbarians by the native peoples. Consider the eloquent Kondiaronk, a Huron-Wendat chief, who in the seventeenth century thrived in what is now Ontario and who the authors gleefully quote at length. I’m not saying he makes Hobbes and Rousseau read like intellectual pygmies because that would be offensive to pygmies, but certainly his jeremiads against European culture bear scrutiny today. He told his French interlocutor:

“I have spent six years reflecting on the state of European society and I still can’t think of a single way they act that is not inhuman, and I genuinely think this can only be the case as long as you stick to your distinctions of ‘mine’ and ‘thine’. To imagine one can live in the country of money and preserve one’s soul is like imagining one could preserve one’s life at the bottom of a lake.”

Graeber was an optimist about the possibility of creating the post-bureaucratic egalitarian society he and Wengrow eulogize in the book’s conclusion. Perhaps, they thought, if our species does endure, our descendants will live in cities governed by neighborhood councils; women will hold the preponderance of formal positions (Kondiaronk, they note, lived happily under a matriarchy); and future land management will be based on caretaking rather than ownership and extraction. Like the Stonehenge slackers or Çatalhöyük hunters, we could create societies we want to live in. It’s an anarchist cri de coeur, though with Marxist undertones: we twenty-first-century yokels have nothing to lose but our chains.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.