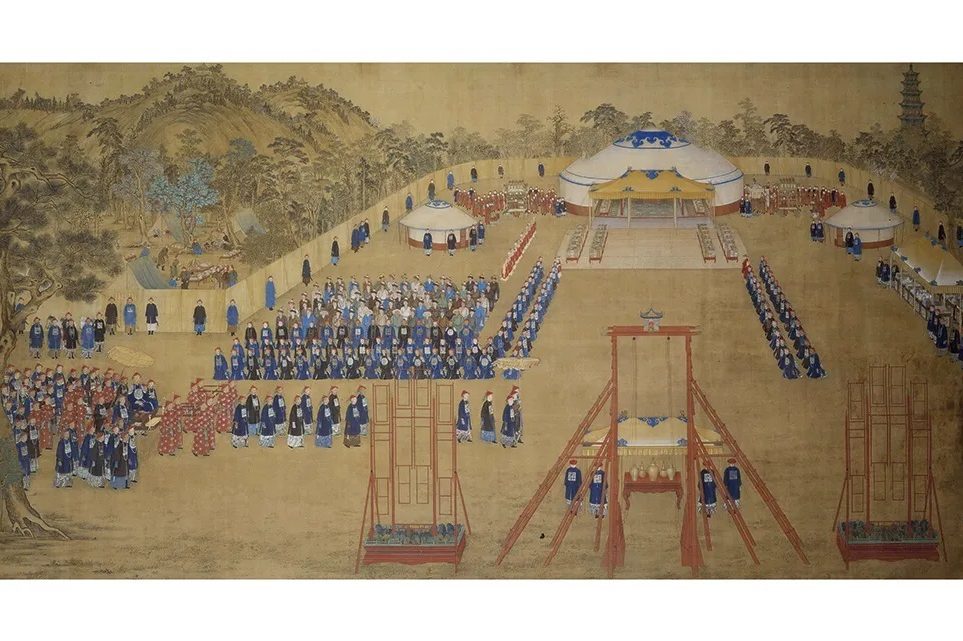

In February 1985 I had the good fortune to be a guest in Hong Kong at the Mandarin hotel’s twenty-first birthday celebration, a lavish three-day reconstruction of the sort of imperial banquet given during the Qing dynasty by the Kangxi emperor (1654-1722) and his grandson the Qianlong emperor (1711-1799). Kangxi started the custom of banqueting during his tours of southern China — he made six between 1684 and 1707. These provincial feasts were relatively informal affairs, often held in a tent, quite different to the stifling protocol of the imperial court at Beijing and combined some aspects of the ruling Manchu “Man banquet” with the native Han Chinese “Han banquet.” The full three-day feast was mostly restricted to Beijing.

It was from these imperial tours, and the burgeoning cookery book publishing industry, exemplified by Recipes from the Garden of Contentment, written in 1792 by the Hangzhou poet Yuan Mei (whom Thomas David DuBois calls “China’s rouge and roguish gourmet”), that a national, as opposed to strictly regional, Chinese cuisine developed. Chefs were then recruited, and ingredients gathered from the whole of the Middle Kingdom. And they and their feasts were the means by which the ethnically different Manchus, who were people of the north, discovered the culinary superiority of the south, particularly of Cantonese chefs. DuBois tells us:

The traditional diet of the Manchus was heavy on meat, especially pork, but also fish and deer. Their annual feasts were orgies of meat, where it was considered impolite to do anything but gorge.

With the passing of time, “the Manchu-Han Feast changed from a precisely managed diplomatic event to a type of cuisine.” I was surprised to learn that my opulent 1985 reconstruction has been reproduced, DuBois says, “by local governments, hotels, tourism boards, television shows and famous chefs.” (I remember how the Mandarin’s Man Wah restaurant was completely redecorated for each dinner, the menus reading like a list of endangered species — civet, bear’s paw, heron — and for the last evening, costumes were made for us that allowed us to appear in imperial drag.)

Most of the “seven banquets” of the book’s title are metaphorical, but DuBois concentrates on one that appears in an 1868 recipe collection, the technique-light Flavoring the Pot, which splits the feast into Han and Manchu tables, “and has now become a veritable butcher’s shop. The twenty-five dishes listed include a whole sheep and suckling pigs’” plus chicken and duck; but “perhaps reflecting the dining practices of the Qing court, beef is notably absent.”

The menus at the Mandarin read like a list of endangered species — civet, bear’s paw, heron

Not only is beef missing; milk, butter and cream, which appear in earlier banquets, have also gone. When I first went to China in 1980, I was told that lactose intolerance was the norm; but in present-day China, with its franchise restaurants and takeout and delivery culture, all dairy foods are consumed, even processed cheese (it took a long time to allay Chinese suspicion of cheese). Milk is imported from New Zealand, but China also has a large home-grown milk industry now, which has been riven by the usual adulteration and corruption scandals.

Policy changes in the 1990s resulting in vast economic growth have led to China catering to its own consumer market and even becoming a net soy bean importer — with soy beans providing most of the country’s cooking oil and the main feed for pigs. By the late 1990s, McDonald’s and KFC were commonplace in China’s cities. Globalization had arrived. Wet markets began to be outflanked by supermarket chains, as were traditional single-outlet restaurants by franchises. For urban dwellers, the key concept was convenience. China’s joining the World Trade Organization, DuBois says, “took existing food trends and added rocket fuel. In many places local favorites had been completely replaced by global brands, national chains and standardized tastes.”

There has, of course, been a reaction to all this. Some consumers still seek authenticity in their diet. This doesn’t only refer to recipes, but the rejection of genetically modified organisms and plastic packaging or embracing organic food. There is even a movement to restore the consumer’s relationship to farming, the Community Supported Agriculture network, with its Little Donkey and Shared Harvest farms. Government departments officially recognize and certify heritage “famous old brands,” such as Jinhua ham, Zhenjiang dark vinegar and Sichuan’s Pi Country bean paste, in parallel with western terroir-certified products such as Champagne or Parmigiano Reggiano. Online commerce has benefitted many of these localized heritage producers, with platforms such as JD.com and Taobao.com.

There is a downside to convenience — not just packing waste, but “what the delivery model has done to restaurant dining.” The delivery app seems to have transformed the larger cities, with hire bikes ubiquitous and ride-hailing turfing out the taxi industry. Starting out in 2010, the two major delivery platforms, Eleme (“are you hungry?”) and Meituan, says DuBois, were each backed by a big tech company, with its existing infrastructure. The success of delivery apps depends on the food being cheap and offering a lot of choice; on the other hand, “even the most carefully prepared meal will suffer significantly from being packed in a plastic box and allowed to cool to room temperature on the back of a scooter,” DuBois points out. And “the solution is the same one they use on aeroplanes: cram the food with strong tastes —!chilli, vinegar, oil, salt and MSG.”

In the 1990s the original hotpot restaurant Hidilao was known for its “extreme hospitality,” giving manicures to sitting customers or sending their shoes out to be cleaned (shades of the Qing emperors’ banquets). It is now a big chain, an early adopter of the “chef-free” restaurant, where the preparation is done off-site in centralized kitchens, and its own locations (centrally owned, not franchised) are still known for their service. “When you order online,” says Dubois (who lives in China), “everything arrives together: food, sauces, paper tablecloths, disposable plates and an electric chafing dish,” which you place in its original box for later collection. A bit like room service.

What is the next chapter in this accessible, riveting history of Chinese food? Alternative protein? Vegan pork mince? Kitchenless apartments? I expect DuBois will be a good guide for China food-watchers.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply