The literature of World War Two bombing campaigns is surprisingly extensive. The books written in Britain largely focus on the night sorties by RAF Bomber Command, but the equally destructive World War Two campaigns by the US 8th Air Force (daylight raids on Germany) and the Luftwaffe (the Netherlands, the Blitz on the UK) are covered too. There is little or no equivalent literature from Germany, although in recent years there have been several deeply researched books by German authors about the destruction of their cities.

The RAF books take all forms. There are authoritative personal histories (pilots, air chiefs, politicians), as well as vernacular accounts (WAAFs, ground crew, rear gunners). There are squadron histories. Biographies of notables like Gibson, Cheshire, Bennett. There are several magisterial histories by, for example Max Hastings, Richard Overy, Denis Richards, Frankland/Webster. The story of the Dambusters’ raid in 1943 has a small library of its own.

Dropping bombs on civilians clearly provokes deep and complicated emotions, and a felt need to explain or justify. The sheer number of books bears witness to this.

One of the most interesting series is by Martin Middlebrook, who writes about Allied air attacks on individual cities, including Nuremberg, Hamburg, Berlin and the German rocket base on Peenemünde Island. Middlebrook draws on personal accounts by participants, witnesses and survivors from both sides and from as many different kinds of involvement as possible: flight and ground crew, anti-aircraft gunners, radar operators, controllers, air raid wardens, night fighter pilots, civilians. The result is a feeling of wholeness, a deep perspective on everything surviving participants did and suffered and endured, as well as what the aircrew went through and what the raids might or might not have achieved.

Now in the spirit of the Middlebrook accounts comes this most comprehensive, revealing and moving book of them all, Sinclair McKay’s Dresden: The Fire and the Darkness. This is a substantial addition to the genre because it describes in almost unbearable detail the deliberate destruction of a major city, a beautiful and historic place the size of Manchester, one that had little or no military value, and was more or less undefended. It was crammed with refugees fleeing the advance of the Soviet Army. No single preceding book on the bombing war has so succinctly summed up the complex responses felt by people directly involved, but also by the world at large.

Because of the time and the circumstance, the long war approaching its end, most of the civilians who were in the city and thus horribly killed or injured were women, children, the elderly and the sick. The final estimate was that at least 25,000 people died. All this was known or anticipated by the controllers of the RAF and the USAAF — also by Winston Churchill, who ultimately gave the go-ahead. (The bombing of Dresden is the one major event of World War Two that Churchill does not mention, even in passing, in his six-volume history of the war.)

Because of pre-knowledge of the target, because it was methodically planned, because Stalin had insisted on it, because all scruples were put aside in the interests of prosecuting a war about to be won, Dresden was deliberately destroyed. Since then the decision to bomb it has been widely described as a war crime. McKay does not agree, and argues cogently against the idea:

‘”War crime” above all implies intentionality and rational decision-making…just as it cannot be assumed that individuals always act with perfect rationality, so the same must be said for entire organizations acting with one will…any conflict of such duration and scale will…create repercussions that start to chip away at the foundations of sanity itself, and in so doing reveal the inherent delicacy of civilization.’

However, such are the dreadful facts recounted by McKay in his book that it is impossible to put the question of criminality aside.

Fighting a war changes almost everything — the perceived necessity for military action overrides normal concerns. Individuals rise to bravery, or fight abroad, or work long hours in factories. Some succumb to fear. Some, many, are killed. The long result is never certain.

In the end, after the war is over, when thoughts of retribution and anger and fear are recollected in tranquillity, it is invariably found that whatever else it has changed the war has not fundamentally altered moral or human values, even if they were set aside for the moment in the heat of the conflict. Historians have a duty to respond not only to the facts and the documentary records of the moment, but also to circumstances, context, hindsight, personal testimony. History is written from the future. The situation clarifies the more time elapses. It is 75 years since the night and day of the Dresden raids. What McKay has to say about the nature of war crime therefore demands the greatest respect. Even so, it is deeply troubling.

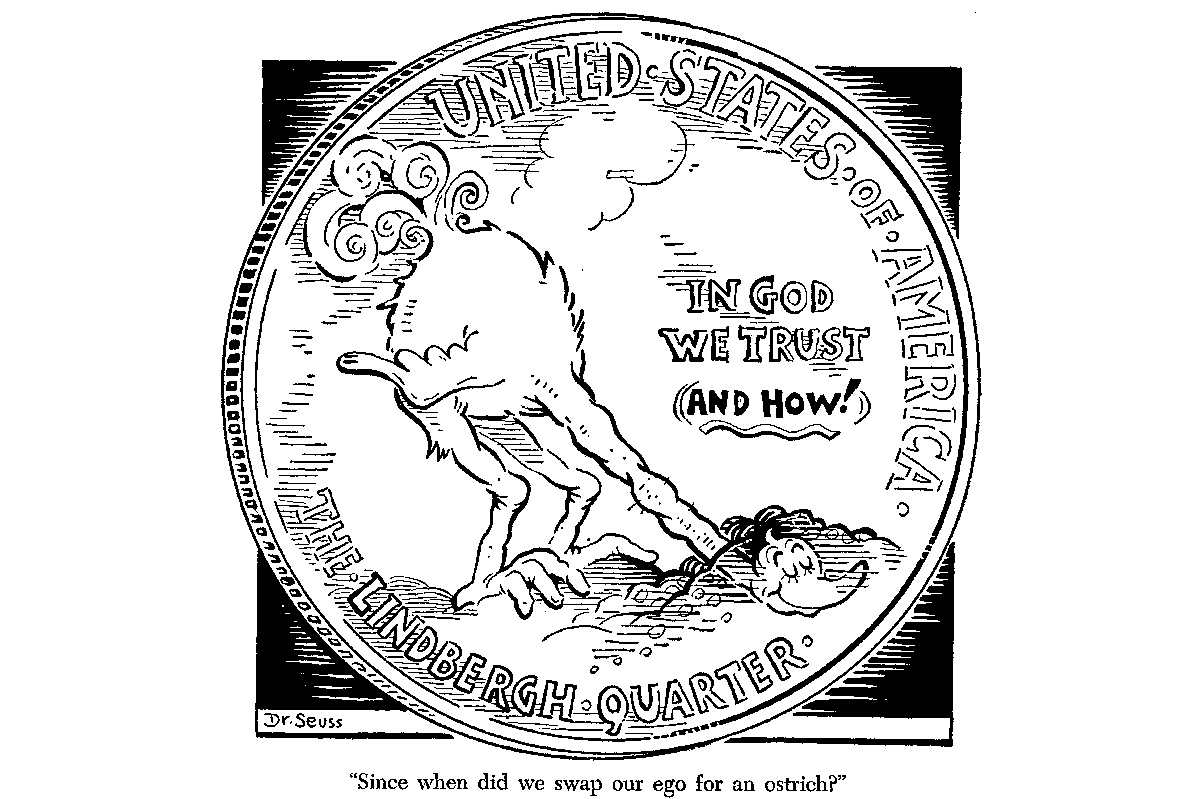

Apart from the German bombing of Guernica in 1937, deliberate attacks on civilians were until then comparatively rare. When World War Two broke out President Roosevelt appealed to both sides to refrain from attacking each other’s cities. Both sides duly refrained for a short period, but soon Warsaw was bombed. Later came the assault on Rotterdam. The damaging Blitz against London and other cities was sustained through six winter months. Later, when Churchill and his Bomber Command chief Arthur Harris launched their long campaign of ‘area bombing’ (i.e. destroying the homes of workers as well as their places of work), much of the impetus, at least in the popular mind, was to pay back to the Germans in kind what they had dished out to ‘us’, the British nation.

From this emerged the central fallacy: that the indiscriminate bombing of German civilians would so destroy their morale that they would overthrow the Nazi party and peace would ensue. Nothing like that followed, just as the bombing of Coventry, Belfast, Birmingham and London had never for a moment weakened the British resolve to see the thing through. Did no one in high places ever point this out?

RAF area bombing became known as strategic. McKay describes it chillingly. The target was marked by fast-flying, low-altitude Mosquito ‘pathfinders’, dropping colored flares to indicate the center of the city. The Lancasters and Halifaxes then arrived, flying as self-protectively high as possible, releasing a deadly combination of huge blast bombs and incendiary devices. Fires broke out everywhere. Within about 20 minutes the deadly work would be done, the bombers departed, the sky became quiet, fires raged. A pause followed, perhaps another 30 minutes, in which survivors started to emerge shaken from shelters, the firefighters and other rescuers began work, the anti-aircraft gunners relaxed. The second RAF wave then arrived from a different direction, more bombers than before, ever more incendiaries. Intense extra fires were started, often combining into an unstoppable firestorm. New levels of traumatic chaos and appalling deaths followed.

This premeditated second level of the raid might be seen by Harris and Churchill as the best way of demoralizing the innocent, but by any standards it was purposeful cruelty because it was planned to be cruel. In the case of Dresden, the day after the RAF had done their work the US 8th Air Force turned up for the coup de grâce, ostensibly to destroy the only remotely remaining legitimate target: the marshaling yards. The tracks were wrecked, but just as many bombs missed their target and landed in the still burning city.

Such raids continued throughout the war against Germany, steadily escalating. Dresden was the biggest of all raids, shocking people in Allied countries, most of whom knew the city symbolized the finest traditions of German liberal values, high culture and beautiful architecture. An American journalist, somehow evading censorship, used the phrase ‘terror bombing’. That was what Joseph Goebbels and Lord Haw-Haw had often accused the RAF of doing, an untruth the British public were used to scoffing at. It was their sons and brothers and husbands who were inside the dangerously vulnerable bombers, doing their bit without complaint, and suffering horrific casualties. (Some 55,500 members of RAF aircrew were killed, and another 18,000 were injured or taken prisoner — these were the highest losses per capita of any of the Allied combatant forces.) But the ‘terror’ tag stuck hurtfully, and the concerns about the criminality of premeditation took hold and have never really died away since.

Dresden was not the last city to fall. Essen, Pforzheim, Leipzig, Dessau, Wuppertal — all took the punishment from the air, even as the Allied armies closed on Berlin. Perhaps Pforzheim was the worst atrocity of all: a small town of watch-makers in the Black Forest, mainly consisting of wooden buildings in narrow streets, Pforzheim lost about a third of its inhabitants and more than 80 percent of its buildings during one night in February 1945.

This is an admirable book, humane, careful with facts, clearly written, drawing on responsible sources, relating every level of the experience during Dresden’s devastation. In this present world of ballistic missiles, unmanned drones, hypersonic aircraft, projectiles with depleted uranium tips, not to mention of course the ever-present threat of nuclear warheads, the lesson from Dresden, for both sides, is as relevant and immediate as ever.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.