It is both disappointing and unsurprising that A-list filmmakers don’t use social media more often. Disappointing, because the opportunity to share candid insights into their craft would be of enormous interest to those who have watched, and often loved, their films; unsurprising, because the vast majority of these men and women wish to make more pictures in the future, and know that the chances of excommunication for excessive candor do not justify entertaining the curious and prurient with some well-chosen putdowns of actors, producers and other creatures of ego.

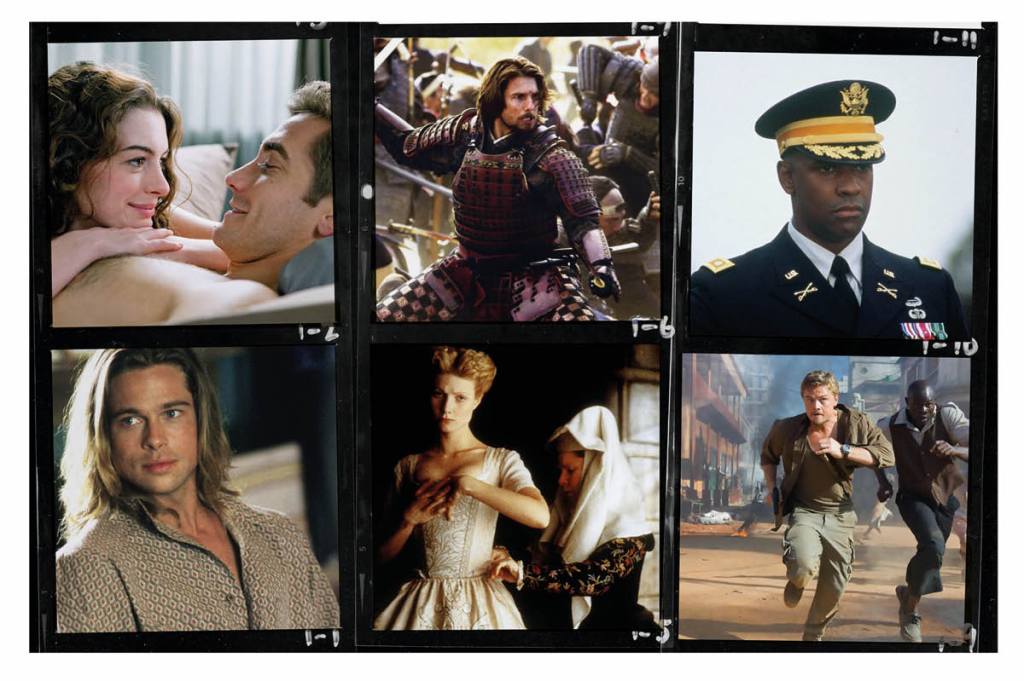

The director Edward Zwick has been an engaging presence on X (or Twitter, as most of us still call it) for a considerable time now, offering unvarnished and insightful accounts of his experiences working on a stream of acclaimed films that have included Glory, Legends of the Fall and The Last Samurai, among others. After beginning his career and making his name, along with his writing and producing partner Marshall Herskovitz, on the trendsetting and immensely popular comedy-drama series Thirtysomething, Zwick briefly became Hollywood’s go-to director for thoughtful, star-studded action films and epics that starred the likes of Tom Cruise, Brad Pitt and Leonardo DiCaprio, only for his career to fall into relative abeyance when the big-budget original pictures he enjoyed making were eclipsed by the CGI-driven superhero films that were, until last year, the surest thing in Hollywood since Steven Spielberg was at his peak.

Zwick, then, is a filmmaker who occupies a strange place in Hollywood. He’s not quite an A-list director, and probably not an auteur either, but his films nonetheless have consistently personal themes that run throughout them, whether it’s the depiction of oppression (in both Glory and his Jewish World War Two epic Defiance), culture-clash dramas (Blood Diamond and The Last Samurai) and wary depictions of the American military machine (The Siege and Courage Under Fire). Some have been more successful than others — and their performance and failure is detailed, in unsentimental fashion, throughout his memoir Hits, Flops and Other Illusions — but all are worth watching at least once, and, at their best, considerably more times than that.

Zwick sets out his credo early on. “To be a director is to be a changeling. I have played both good cop and bad, psychoanalyst, flirt, camp counselor, drug counselor, scourge, tutor, BFF, coach, con artist, confidant and co-conspirator. Also, a heartless son of a bitch.” He does not spare himself when it comes to his successes and failures, especially when it comes to the A-list actors who populate his films, writing “my own relationships with movie stars have ranged from the deliriously happy to the unimaginably combative,” and he writes in one of the early chapters that his intention is to name names, or, as he puts it, “if I intend to write about what it’s really like to make movies, I might as well suck it up and tell it like it is, even at the risk of causing some hurt.”

Many major industry figures will undoubtedly be pleased how they are presented here: the likes of DiCaprio, Anne Hathaway and Jake Gyllenhaal are portrayed as friendly, hard-working and passionate about their craft, although Zwick includes a mild dig at Hathaway for enthusiastically accepting a role in an original script written for her, and then turning it down a few weeks later via her manager.

Others come across less well. Brad Pitt, whom Zwick arguably was responsible for turning into an A-list star with his performance on the soapy but visually impressive epic Legends of the Fall, fights his director and then expresses disappointment in the finished film because of the removal of a shot indicating his character’s (temporary) descent into madness. Tom Cruise is presented in much the same way that he appears in virtually every other memoir or journalistic account — manically upbeat, focused and “a complete enigma,” according to Zwick — and Denzel Washington’s remarkable talents as both man and actor do not extend to his suffering fools remotely gladly, as is hinted several times in what is otherwise a laudatory account of his performances in Zwick’s films Glory — for which he won an Oscar — and Courage Under Fire. And Bruce Willis, who has a sullenly villainous performance as a power-crazed general opposite Washington in 1998’s The Siege, is damned as unprepared and disengaged, to say nothing of “wooden and uncomfortable.” As his director writes, “Bruce barely managed to stumble his way through and the authenticity of the third act was irreparably hurt by his toothless performance.” Ouch.

Still, if this is harsh criticism — and Zwick at least acknowledges that it may have been the early onset of the aphasia that the world now knows afflicts that much-beloved actor, although he managed perfectly well the following year in M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense — then it is nothing as compared to the two most interesting pen portraits in the book, of Matthew Broderick and Julia Roberts. Broderick, for decades now regarded as one of the nicest actors in Hollywood and on Broadway — perhaps because of his well-burnished comic persona, honed in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and revamped, or recycled, many times since — here emerges as a petulant nightmare, making Zwick’s life hell on the set of Glory with his endless bizarre demands and obvious dissatisfaction with the film and the attention given to his character.

As the director writes, metaphorical sleeves rolled up, “Nothing I might have done could possibly rival Matthew’s role in the theater of cruelty that was about to begin,” although he does at least acknowledge that “he has long since apologized for his behavior and I forgave him.” Yet even worse than Broderick is his domineering mother Patsy, whom Zwick calls “contemptuous, demeaning and volatile,” and whom he compares unfavorably to Grendel’s mother. You do not imagine that there is much chance of Broderick and Zwick ever working together after the former reads this book.

More interesting still is the chapter on Shakespeare in Love, which Zwick won an Oscar for producing, even if his involvement was limited to having developed the picture in the early Nineties, with Roberts cast in the role eventually assumed by Gwyneth Paltrow. All the elements of success were there, not least the brilliant Tom Stoppard screenplay, but it was derailed by Roberts’s refusal to star opposite anyone save Daniel Day-Lewis, who was already promised to the IRA drama In the Name of the Father.

Roberts attempted, metaphorically or literally — one senses the uneasy hand of lawyers at this juncture — to seduce Day-Lewis but was unsuccessful, and consequently pulled out of the picture, costing an irate studio $6 million. When it was later revived with Harvey Weinstein — “a villain worthy of Shakespeare’s pen” — as its producer, Zwick was given short shrift and later only included in the film’s credits thanks to costly, difficult litigation. When the film won Best Picture, thanks to Weinstein’s energetic/bullying campaigning strategies, Zwick ended up literally and metaphorically sidelined on stage, holding an Oscar for a film he had been booted off and feeling vexed about it all.

Hits, Flops and Other Illusions is a fascinating book, both for what it includes and what it either omits or deals with in parentheses. Zwick is frequently hard on himself — “I am a movie director masquerading as a rational human being” — but apart from occasional references to recreationall drug use and ego-driven on-set clashes, emerges as a likable, thoughtful sort, a world away from the monsters he alludes to having had grim experiences with. There are flourishes which may not be to all tastes, as when he writes “these stories can also be read as a kind of pilgrim’s progress: a sentimental journey from innocence to experience” — but there is also a welcome self-deprecation of this endeavor. After he suggests that his style of autobiography has been inspired by the work of Billy Wilder, Sidney Lumet and, naturally, William Goldman, he also suggests “it seems more than a little presumptuous to assume anybody will be interested in my own misadventures.”

It is a shame that Zwick is no longer making the films that he came to prominence with, thanks to Blood Diamond being openly described by the studio boss as the last of its kind, “a big movie just for adults.” Now in his seventies, and a survivor of non-Hodgkin lymphoma — he suffered from the illness just before making the Gyllenhaal/Hathaway rom-com Love And Other Drugs, informing its strange mixture of sentiment and sexual frankness — he adopts the role of elder statesman with ease and wit, telling tales with charm and candor that ensure that this memoir will be regarded favorably. He may write that “Hollywood stories are necessarily suspect,” but this particular filmmaker’s odyssey deserves a happy ending.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply