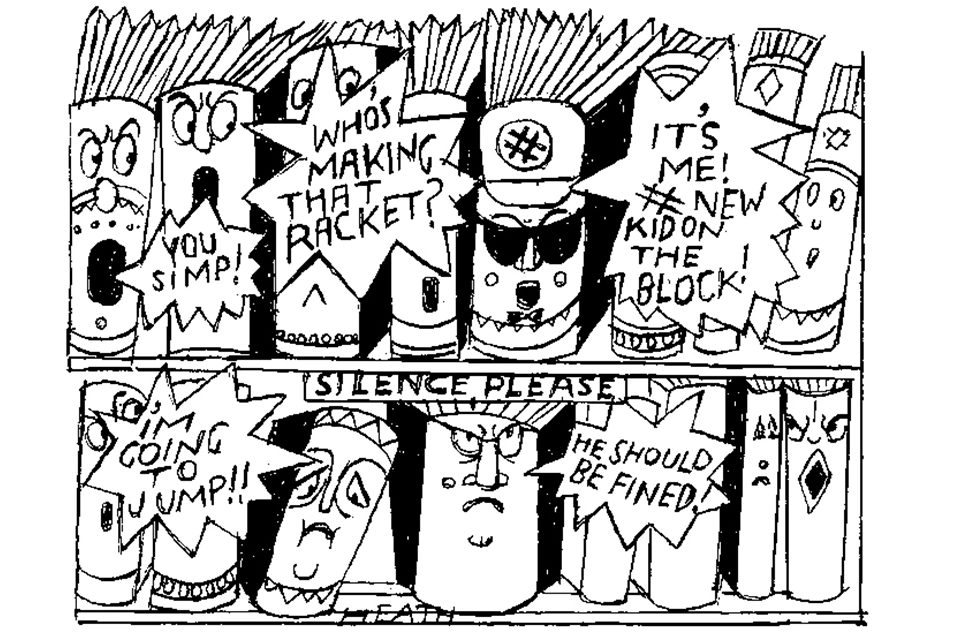

There is a growing fashion for fake books. Not fake as in written by a series of AI prompts, but fake as in things — cleverly painted empty boxes, or a facade of spines glued to a wall — designed to mislead the casual onlooker into thinking that they are books.

A recent New York Times article highlighted the trend. It featured various interior designers offering spurious arguments in favor of fakes over real books: they can be a practical solution for hard-to-reach shelves; a smart example of up-cycling unwanted volumes destined for landfill; useful and humorous storage boxes. Neat, quirky design solutions are, however, the least of it. This fashion signals a profound shift in our attitude to books. Rather than perceiving them as holders of information, stores of stories, we are increasingly perceiving them as just things — albeit pretty things.

Books have never been more beautiful. Even the paperback, first conceived as a cheap option for the masses, has become seductive, with eye-popping covers featuring expert designs and shiny colors. Jamie Keenan, a veteran book designer whose clients include Penguin, Knopf and Vintage, explains: “It’s easier now to get special colors, or metallics for covers, to get them dye cut or embossed. Everything’s much more sophisticated than it was twenty years ago.”

The current commitment to producing beautiful books came about in part as a reaction to eBooks. When those took off in 2006-07, the sudden ease of consuming books electronically, divorcing their content from their materiality and transforming them into weightless, instantly downloadable and low-cost items, spurred publishers to work hard to make physical editions more appealing. As Keenan says: “There’s far more understanding of what a cover can do in terms of selling the book.”

These covers are at their most dazzling when they flash before our eyes in the scroll of social media. Bookstagram (with 90.1 million posts) and BookTok (138.4 billion views) have had a pronounced impact on sales. It’s become unusual to enter a bookshop and not see a BookTok table, piled high with bestsellers that owe their success to social media. James Daunt, Waterstones managing director and Barnes & Noble CEO, recalls: “When BookTok first kicked off, it was very obvious that bookshops — as a place of performance, effectively providing a backdrop — could be a place for it, and that was really exciting.” Daunt is known for prioritizing attractive displays in his shops, and is happy that “social media has now been harnessed to amplify that. It’s nothing but good, a very positive thing.”

I am all for anything that increases the popularity of books, but a closer look at our treatment of them on social media has made me think more carefully about what exactly is going on. Of course there are exceptions, but for the most part, Bookstagram and BookTok are platforms to share highly styled scenes featuring a book, rather than a nuanced or meaningful engagement with its characters and ideas. Daunt enthuses over the “fun young people are having with books,” but this fun tends to revolve around a book’s appearance, not its content.

A sample scroll through Bookstagram reveals the following recent topics: “Covers with flowers,” “Can you spot a favorite type of edge in my shelfie?” and “Minimalist Monday.” If a post does engage with content, it is certainly brief. On BookTok, for instance, you might get a short video (most are under thirty seconds) of someone tearing their hair out, with the text, “Me when the enemies become lovers,” or a bullet point flashing up beside a book noting, “Serious page-turner.” Hashtag stats confirm the predilection for style over substance. On Instagram, #politicsbooks and #economicsbooks have a mere 1,000-plus posts, whereas #bluebookstack has 14,000, and #rainbowbooks 90,000. On TikTok, #bookreview has 875 million views, but #bookshelf 2.7 billion.

This focus on appearance suits social media influencers well. As even the most amateur aspiring influencer knows, the more you post, the more engagement you get. Instagram authorities, such as the social media scheduler Later, suggest posting three to ten times a week, and TikTok recommends one to four videos a day. It is impossible to read enough books to meet this demand, so focusing on how a book looks is a neat cheat.

This shift in focus has an alarming impact when taken beyond social media. If we fall into the habit of prioritizing how our books look, we might well begin to arrange them by physical feature, rather than topic or author. If we arrange our shelves by, say, color gradient, we might easily look to buy a blue book rather than a great novel. Daunt jokes that he doesn’t mind, “so long as it’s a good blue book.” However with the increasing focus on the book’s outside, it’s only a small step to remove the inside altogether. It is a terrible irony that we have worked so hard creating beautiful covetable objects to save books from death by Kindle only for our success to signal their demise in a different way.

But what does it matter if books as holders of words — and worlds — become increasingly redundant? We are deep in the digital age and if our books are becoming empty, then our screens are full of stories told in arresting, attention-grabbing ways. Personally, I treasure the experience of reading a book over engaging with a screen, but most people feel otherwise. A 2021 American survey showed the average reading time was just 16.2 minutes per day as opposed to 168 minutes spent watching television. Why not consume your drama in eight episodes rather than between paper covers? Who needs a history tome when there’s a documentary? Or a manual when there’s a YouTube video? Why shouldn’t we put fake books on our shelves if we get our stories elsewhere? The National Literacy Trust recently noted the “striking” similarity between what children get from reading and what they get from playing video games, including “immersion in a story” and “empathy.”

Perhaps books were only ever going to have a temporary role as our holders of stories. Before they arrived, we used to come together to share tales, and enjoyed the effects of gesture and voice in our lost culture of oral storytelling. Maybe we’ve missed this in the solitary experience of reading books, and that’s what we’re endeavoring to rediscover via screens. Are BookTokkers the bards of the twenty-first century?

Even so, those who, like me, still rail against this trend for style over substance must resolve to be a little nosier. The fact is that fake books can convince only if nobody tries to read them.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.