My book on Dante Alighieri was due to come out in Chinese translation later this year, but first I had to consent to sizable cuts. Even by the standards of other authoritarian states the Beijing censors struck me as overzealous. It seems odd that the medieval Italian poet could cause such unease among modern-day totalitarians. A sanitized Chinese communist version of my book did not sit well with the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death in 1321, and in the end I withheld permission.

The cuts were the work of Beijing’s blandly named Institute for World Religions. The institute undertakes ‘book cleansing’ operations on behalf of the state. No book can be published legally in China today without being vetted. In their solemn appraisal the censors insisted that all references to Islam be removed. Why?

Dante inflicts a punishment so grotesque on the Prophet Mohammed in Canto 28 of the Inferno that Muslims might well protest. The Prophet’s body is split from end to end so that his entrails dangle out amid excrement; he is punished as a ‘sower of discord’. Beijing is not known to be tolerant of China’s 22 million-strong Muslim minority; why then were the censors so unhappy with my 20 pages on Dante’s less than flattering portrayal of Islam?

The reason is that even hostile interpretations of Islam are discouraged today in Xi Jinping’s China. Thus the censors removed from my book a color-plate illustration of Giovanni da Modena’s 15th-century fresco depicting Mohammed’s graphic mortification by a bat-winged devil creature. The Last Judgment fresco, inspired by Dante, continues a tradition of medieval allegorical books and poems which portrayed Muslims as renegades from Christianity. (In 2002, alarmingly, there was an Islamist plot to blow up the Bologna cathedral where the fresco is displayed.) Mohammed’s physical sundering by Dante is certainly gruesome. Yet Chinese Dante scholars and translators (according to a Chinese friend of mine in Beijing) have never made much of the connection between the Inferno and Islam. Now suddenly they do.

Also censored were 15 pages on Dante and Martin Luther. Dante is often viewed as a pioneer of the Reformation (he condemned a number of popes to hell, after all). In China, though, any talk of his proto-Lutheran intransigence is deemed potentially ‘harmful to public morality’, and not permitted. Less clear to me was why sections on the rivalry between the Guelfs and Ghibellines were taken out. Not even Dante understood why these Italian dynasties fought so bitterly and long. (‘Exeunt Guelfs and Ghibellines, still fighting’, runs a line in a Max Beerbohm’s spoof play Savonarola Brown.)

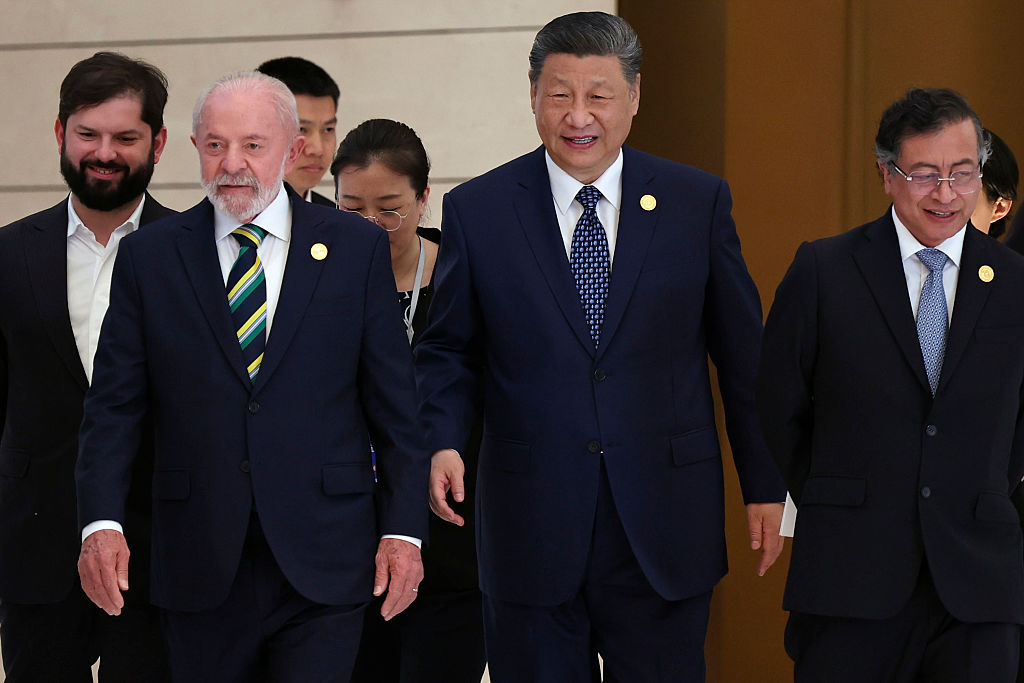

Censorship intensified across the board in China after 2012 when Xi became the general secretary of the Communist party. Xi was shaped by the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76, when ‘problem citizens’ were shut away in reformatories and sometimes had their vocal cords surgically severed (like the traitors trapped in ice in Canto 34 of the Inferno, they had no right to speak). Ludicrously, internet images of Winnie-the-Pooh were blocked in 2017 when the red-shirted bear’s appearance was compared to that of the portly Xi. Brokeback Mountain and other foreign films that deviate from the party line on homosexuality are banned.

Homosexuals and others who have sinned ‘against nature’ are consigned by Dante to the seventh circle of hell in the Inferno. Among these poor doomed souls is the 13th-century humanist and diehard Guelf Brunetto Latini, Dante’s old tutor. Latini cuts an oddly dignified figure as he wanders the afterlife in penury and exile. At some level Dante identified with him. Sin is often ambiguous and many-faceted in Dante (the sinner may have virtues as well as faults). However, ambiguities of this sort have no place in a regime that views even Winnie-the-Pooh as a hazard, and knows only black and white. Latini’s name was expunged from my book entirely.

China’s rigorous and often absurd censorship is even more disconcerting when China’s diplomats successfully apply it beyond their country’s borders. This week, following pressure from the Chinese consulate in Hamburg, the German publishing house Carlsen pulped copies of a children’s book that dared to suggest the coronavirus originated in Wuhan. The destruction of A Corona Rainbow for Anna and Moritz is no small victory for Beijing in its campaign to deflect blame for the pandemic.

My own experience of censorship was a distasteful affair, that ran counter to China’s vaunted transition to the free market. In a carefully worded letter to me, the Chinese publisher apologized for the whole tedious business (‘We are very sorry for this strange publication procedure in our country’) but if the deletions demanded by the Institute for World Religions were not made, there could be no book. Bizarrely, much of what the Institute asked me to remove already exists in footnotes and annotations to the five Chinese-language versions of Dante’s Inferno currently available. So why bother? The Institute’s word was final; I felt I had no choice but to tell the censors where to stick their deletions. There ought to be a special place in hell for them.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.