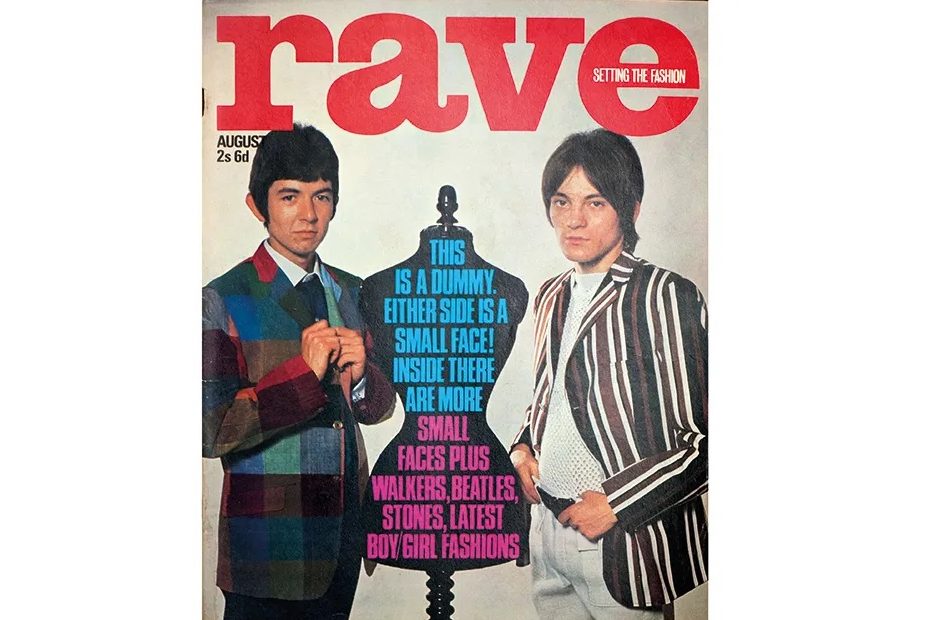

Thirty years ago, I worked for a while in a shop in Soho selling vintage newspapers and magazines. The holy grail for some customers might be the 1955 Playboy featuring Bettie Page or the 1976 Daily Mirror with the Sex Pistols’ “Filth & the Fury” headline. But those of a born-again Mod persuasion were usually looking for 1960s publications with the Small Faces on the cover — preferably the August 1966 copy of the teenage music and fashion bible Rave, showing Ronnie Lane and Steve Marriott from that most style-conscious of bands, complete with a double-page poster of the group inside.

Now, nearly six decades after their formation, there is, arguably, an even greater interest in the Small Faces, who, after the singer Marriott left, evolved into the equally well-regarded Faces, teaming up with Rod Stewart and Ron Wood. There have been various books about the Small Faces, and also Marriott, while the keyboard player Ian McLagen and the drummer Kenney Jones both wrote autobiographies. But this is the first work devoted to the bass player Ronnie Lane.

This may sound like an overcrowded market, when certain million-selling performers deliver a smoothly polished and utterly sterile “live” experience by miming to backing tracks onstage and one of the biggest shows in London relies on holograms of a group which split up forty-one years ago. But the reading public’s appetite for stories about the times when music still had rough edges and no safety net seems ever greater.

Anyone looking for the last characteristics would find no shortage of them in Lane’s career, and Caroline and David Stafford display the same dry wit and careful research that informed their previous excellent biographies of figures such as Lionel Bart or Kenny Everett. They trace Ronnie’s life from East End beginnings to stardom in the mid-1960s beat boom, and the decades-long progress of the hereditary multiple sclerosis which eventually claimed him.

Born in 1946 and a youthful fan of Hollywood singing cowboys, Lane was given a ukulele by his father at the age of six and was soon earning pennies busking for passengers at a nearby bus stop. His trajectory resembles that of many British musicians of the 1960s — the fledgling teenage bands, dead-end jobs, then the big break, but with the specter of illness already waiting in the wings throughout the years of fame. Despite the tragic elements of this story, it is also frequently very amusing, as witness the authors’ description of how in those days a typical act might fare in the music business:

“The band loses all its money to bent managers and dodgy coke dealers, then one day the bass player finds the drummer in bed with his wife, or the lead singer finds the keyboard player in bed with her husband, or everybody finds everybody else in bed with members of Fleetwood Mac and the whole thing explodes. These events are usually described as ‘musical differences’”

McLagen once remarked “I think we all enjoyed a drink first, playing second,” and excessive alcohol intake certainly plays a key role in many of the events described here. Lane’s final days with the Faces sound particularly grim, with onstage fights, verbal abuse and members locking themselves in separate dressing rooms. Denied almost until his death the royalties to the Small Faces million-sellers he had co-written, Ronnie had also severely depleted his own finances by quitting the Faces in 1973 and sinking much of his wealth into the Passing Show. This was his ambitious traveling circus with folk music that toured the UK with the best of ideals, yet hemorrhaged money in all directions. Some of his own musicians also had complaints, such as the sax player Jimmy Jewell, who departed mid-tour after a dispute about wages and conditions, leaving a note which read: “Goodbye cruel circus, I’m off to join the world.”

Through it all, Ronnie remains something of an unknowable character, despite the testimony from many who were close to him. By the early 1980s, his ability to perform onstage, and sometimes even to walk, was becoming seriously compromised, although people often assumed that drink was the cause. Long before his death in 1997, he had moved to America, initially for experimental snake venom treatment, which failed, although, as he wryly commented: “If any mosquito bites me it dies instantly.”

Anymore for Anymore: The Ronnie Lane Story by Caroline and David Stafford is a thoughtful study of how Ronnie coped both with fame and encroaching illness, which doesn’t shy away from his contradictions, but is written with genuine fondness, a sentiment apparently shared by many who knew him. As John Peel later recalled of the Faces:

I saw them disappear into their dressing room that was full of scantily clad women and so forth and the sound of breaking glass and curries being flung against walls and so on, and I thought to myself: ‘Actually, these people are having a much better time than I am.’

For a while there, they probably were.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply