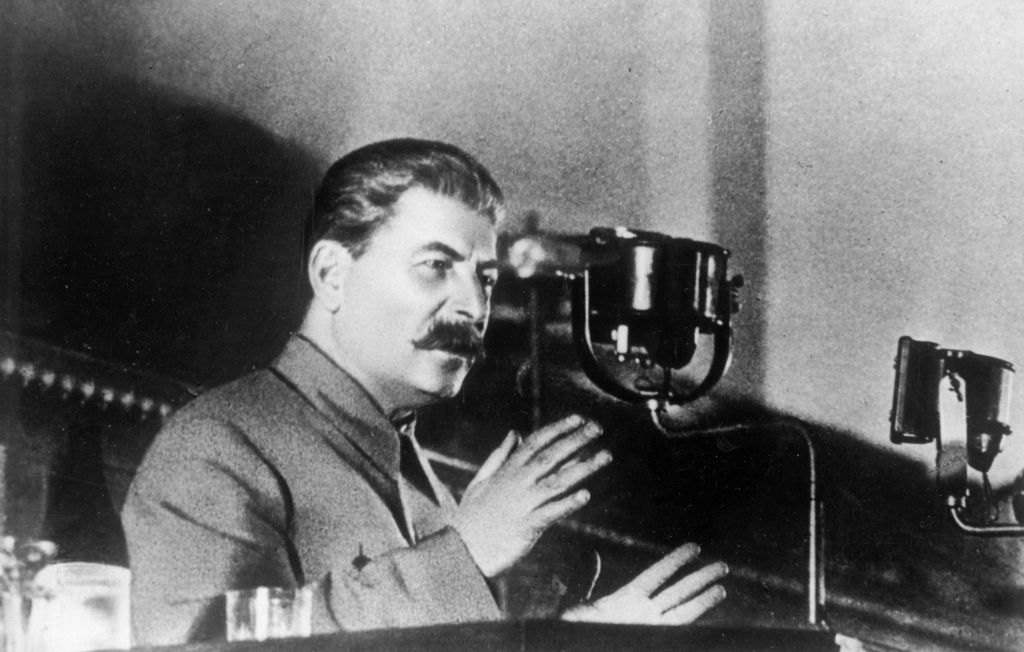

On June 22, 1941, the German army invaded the Soviet Union. Over the next four months, the Wehrmacht blasted through the Soviet defenses, taking millions prisoner and destroying thousands of tanks. By early December, German scouts were purportedly within site of the Kremlin. Even though the Wehrmacht was forced back from the gates of Moscow by the Red Army, the renewed German offensive in spring 1942 threatened to deliver the coup de grâce to the Soviet Union. That it didn’t was due to an unlikely alliance between British prime minister Winston Churchill, US president Franklin D. Roosevelt and Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.

In his new book The Stalin Affair: The Impossible Alliance That Won the War, historian Giles Milton tells the story of how Churchill and Roosevelt were able to forge close relationships with Stalin, a man they loathed and whose regime they detested, in order to defeat Adolf Hitler. But the book’s real interest lies in its depiction of individuals such as the wealthy and good-looking American businessman Averell Harriman, his vivacious daughter Kathleen and maverick bisexual British ambassador Archie Kerr. They made the Grand Alliance work by giving frank advice to their bosses, usually behind the scenes, opening doors that would otherwise be closed and getting the job done.

In the hands of a less skilled writer, The Stalin Affair could easily have been rather dull. But Milton turns this true story of high politics into an addictive, gossipy, alcohol-fueled, action-packed thriller that sweeps the reader effortlessly through the ups — and downs — of the alliance, from its forging in June 1941, to the Yalta Conference in February 1945 and its collapse into acrimony and the beginning of the Cold War. There’s a good reason why an earlier title for the book was Vodka with Stalin.

Milton adeptly uses a previously unseen collection of hundreds of personal letters written by Kathy Harriman, shared with him by her son, to make readers feel that they too can hear the Panzers at the gates of Moscow, or imagine they are knocking back vodka shots with foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov.

Unlike the appropriately claustrophobic atmosphere of Milton’s previous work, Checkmate in Berlin: The First Battle of the Cold War, his new book (in effect a prequel) is cinematic in its approach. It sweeps the reader from the German invasion of the USSR to lunches at Chequers, the British prime minister’s country retreat, and from banquets in the Nicholas II throne room in the Kremlin to the depths of the Katyn forest, where more than 20,000 Polish officers were executed by the Soviet secret police in 1940. Darkness is never far away in The Stalin Affair.

Milton’s skill as a storyteller is such that he can combine epic story arcs like these with smaller-scale, revealing anecdotes. When the invasion begins, he crosscuts to the leaders as they hear of the event: Marshal Zhukov tells a bleary-eyed Stalin over the phone that the Germans have invaded, and then shouts at him, “Do you understand?” when the dictator is silent in disbelief. Churchill awakes at Chequers to the news. His quick decision to commit Britain to come to the aid of the Soviet Union is broadcast over the radio later that day, despite the opposition of his advisors. “Any man or state who fights against Nazism will have our aid,” he growls. In Washington, Roosevelt is more cautious: huddled with his advisors, he issues no statement and gives no emergency press conference. Pearl Harbor is less than six months away.

Milton perfectly captures Stalin’s growing despair at the destruction of his army, tracking the way it turns into depression and paralysis. “Lenin founded our state… and we fucked it up,” says Stalin. Later he tells his ministers, “Everything is lost… I give up.”

On that cliffhanger, the author introduces us to Averell and Kathy Harriman. In spring 1941, the American millionaire had been sent as an envoy to Britain to expedite Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease program, the policy that allowed the US to give weapons and supplies to Britain and Allied nations free of charge on the basis that the aid was vital for the defense of the United States. For Harriman it was “the job of a lifetime” because he was able to deal directly with Churchill, answered only to Roosevelt and was given carte blanche to get the job done.

Harriman’s experience of his first air raid over London led him to his highly risky affair with Pamela Churchill, the prime minister’s daughter-in-law, who, untroubled by their twenty-eight-year age gap, “was determined to spend the night with him.” As an observer wryly notes, “a big bombing raid is a very good way to get into bed with somebody.”

The American businessman’s “unusually close relationship” with his spirited twenty-something daughter Kathy meant that she soon followed him to the UK, where as a journalist she wrote popular eyewitness accounts of the plucky British during the Blitz. Averell rented a house for his lover and his daughter to share. Kathy described her father’s lover as “a bitch… who only looks out for herself,” but subsequently became very good friends with her, although the affair was something they never discussed.

Milton delves skillfully into the minutiae of the period, bringing his protagonists alive. He makes the reader want to dally, enjoy and chew over every detail of the Harrimans’ lives, at the same time wanting to know the answer to a question: how is Stalin going to survive?

He is portrayed here as an almost pathetic figure. For days after the invasion Stalin wasn’t seen in public. Diplomats thought he might have fled to Turkey or China. “But the truth was much worse,” according to Milton. The man who ordered the deaths of over a million men and women in his Great Purge hadn’t washed or changed his clothes for days. He wandered his dacha in a daze. It was only on June 30, when his ministers formed the State Defense Committee in his absence, that he was shaken out of his stupor. Soon afterward he gave his first radio broadcast since 1938.

But the Red Army’s defeats continued, and Arctic convoys carrying urgently needed British and American aid were struggling to reach the Soviet Union. Averell Harriman traveled to Moscow to see Stalin. His inspired solution to the problem is one of the most fascinating of the many little-known stories in the book, and perhaps the most important. Harriman, who had begun as a railroad magnate, came up with a plan for the United States to take over the running of the Trans-Iranian Railway linking the Persian Gulf with the Caspian Sea at the Russian border, which the British had been running like a “suburban branch line.”

They then applied American engineering brilliance, railroad know-how and muscle — in the form of 28,000 US troops — to some of the “roughest, toughest, railroading” in the world, which transported, at the peak of its operation, the equivalent in weight of around 50,000 jeeps to the Soviet Union every week. The result was that American jeeps and trucks became the savior of the Red Army.

It may be true that great forces shape history, and that it was inevitable that the economic muscle of the British Empire, the Soviet Union and the United States would crush Nazi Germany in the end. But it is also true that sometimes those forces need a little help.

The author captures this perfectly in his account of Churchill’s visit to Stalin in August 1942. The prime minister knew he had to forge a friendship with the Soviet dictator that would be the equal of his bond with President Roosevelt, but Stalin reacted furiously to the news that the opening of a second front was going to be delayed and accused the British of cowardice. Later, drinking heavily, Churchill referred to Stalin as “an ignorant peasant” and described the Russians as “not human beings at all” in a room he knew to be bugged. The gap between imperialist aristocrat and revolutionary peasant was, perhaps, too wide to bridge.

Churchill’s anger only increased when Stalin sneered in an after-dinner toast about “the gross stupidities in concept and execution” of the World War One military debacle at Gallipoli — which Stalin knew had been the responsibility of Churchill. Now it was the prime minister’s turn to rage. As Milton highlights, it fell to Archie Kerr to persuade Churchill to stay in Moscow. Summoning up his courage, Kerr told Churchill that he “had had great faith in him [Churchill], and he had disappointed me…” As his anger at Kerr’s insolence subsided, Churchill asked, “So, you think this all my fault? …Well, what do you want me to do about it?”

The book can be deliciously gossipy, but Milton doesn’t shy away from difficult issues, such as the strange appeal of Stalin, which even the reader can feel. It is evident in the way Churchill and Roosevelt seemed to compete for his attention, even undermining each other to get it — see the former’s “naughty document” in which he proposed dividing Eastern Europe in half with Stalin, or the latter’s only half-joking suggestion that they sort out Britain’s India problem without Churchill. It was a rivalry that helped make them blind to — even naïve about — Stalin’s murderous intentions in Eastern Europe.

The story of the Grand Alliance is a familiar one, but Milton consummately retells it as a cinematic thriller. There is of plenty of heft in The Stalin Affair for the serious reader to enjoy, and lightness to enthrall the casual book buyer. Milton harnesses all his experience to deliver another exemplary piece of popular history.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply