I’ve been reliably informed that Hamilton is now cringe.

Constance Grady of Vox explains, drawing on a scene from the recent reboot of Gossip Girl:

“You know, I saw Hamilton… before it went on Broadway,” brags one of the teens, hoping to impress his cool new girlfriend Zoya. “You into that play?”

Zoya, the wokest of the group and the one with the most sophisticated literary taste, sighs deeply and rolls her eyes. “No doubt it’s a work of art,” she allows. “But …”

Zoya doesn’t finish her sentence. She doesn’t have to; by now, the critiques of Hamilton are so well established that the audience can fill in the blanks on its own: Hamilton, according to current conventional cool-person wisdom, glorifies the slave-owning and genocidal Founding Fathers while erasing the lives and legacies of the people of color who were actually alive in the Revolutionary era. It is no longer considered to be self-evidently virtuous or self-evidently great.

If Grady is right (which certainly appears to be the case, judging from the universal eye roll that greeted the Hamilton cast’s performance at Nancy Pelosi’s January 6 anniversary liturgy), then the very survival of the American Republic is at risk.

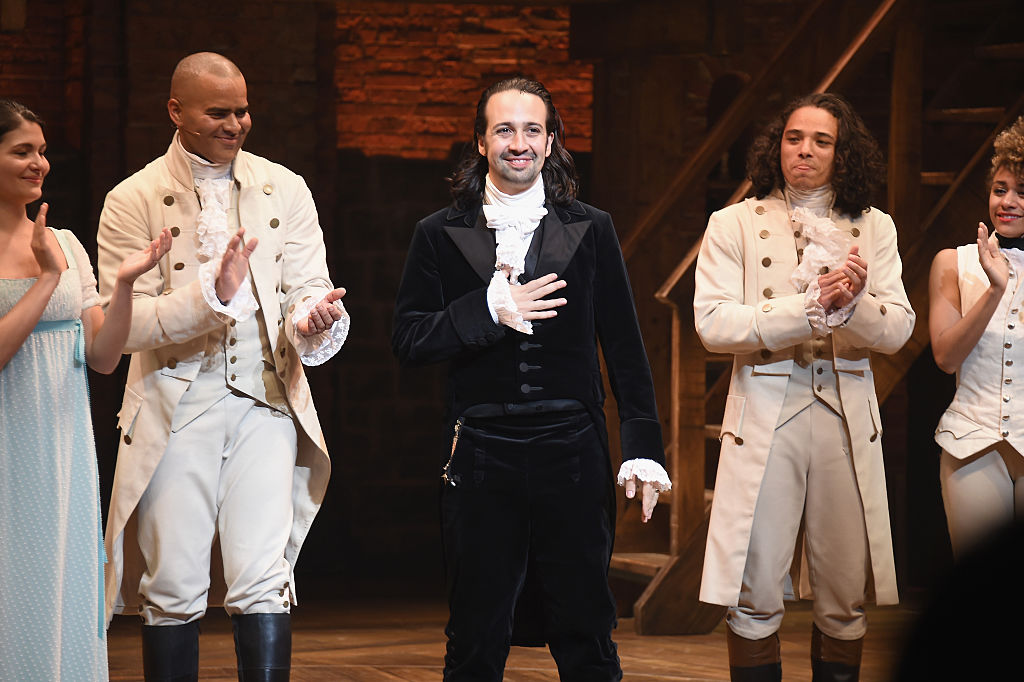

Despite being at least theater-kid-adjacent throughout my college years, I was only ever a moderate fan of Hamilton. I was, however, glad as hell it existed. Theater nerds tend to be wince-inducing social-justice warriors, always yammering on about capitalism and “erasure” and stolen land. That Lin-Manuel Miranda could successfully pitch the Founders to that crowd with his adaptation of Ron Chernow’s biography — the sort of book usually read exclusively by conservative Boomer dads — seemed like a real step toward constructing a shared, usable past on which national unity could rest firm.

Sure, Hamilton was, as another Vox piece points out, American Revolution fan-fiction “talking back to the canon.” It was a conscious re-interpretation of the history that dealt loosely with the facts. But if that was what it took to convince young progressives that the Founding was cool, then I was for it.

Miranda made a herculean effort. He framed the men of ’76 as sexy, brash, hip, “young, scrappy and hungry.” Hamilton himself appeared as an upstart immigrant whose literary gifts propelled him from squalor to prominence. Rapper Nas picked up on the implicit parallel, contributing the song “Wrote My Way Out” to the Hamilton Mixtape. “I picked up the pen like Hamilton,” he raps, recalling his childhood on the mean streets of Queens with a line that would have sounded unbelievably corny during the Bush administration.

But it wasn’t enough. In the end, there was just no salvaging the Founders. Hamilton, the last seawall holding back the tide of the 1619 Project, has failed us. Now every statue must fall, or at least be slapped with a warning label. Danger: Problematic. The Founding might never be cool again.

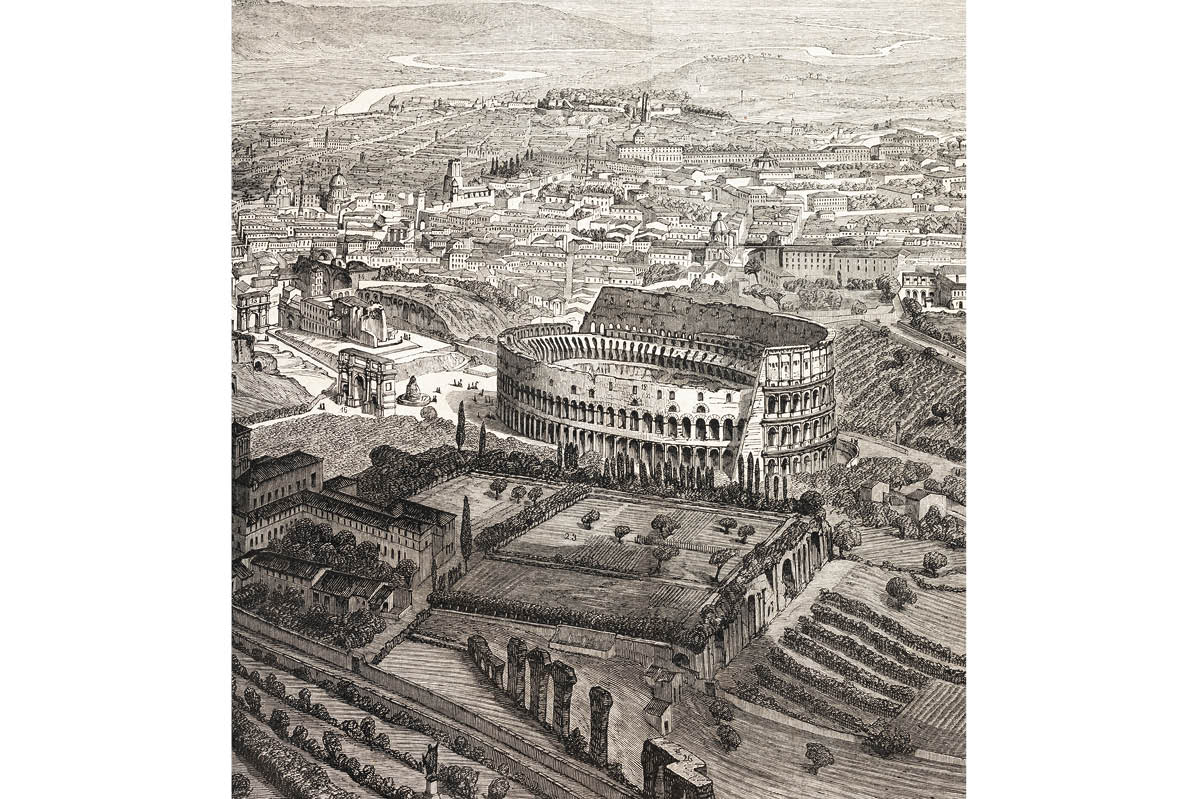

During a recent conversation with a friend, I opined that no civilization had ever turned against its own founding myths and principles to the extent America has. He disagreed and pointed me toward the Roman Empire in the fourth century.

I think he was right. Conservative Roman pagans probably would have experienced ascendent Christianity the same way conservative American Christians perceive the woke revolution.

Parallels abound. The early Christians toppled idols and reconsecrated pagan temples just as George Floyd mobs demanded that monuments to America’s pantheon be removed or recontextualized. Christian concern for the marginalized (especially slaves and women) appeared to threaten social stability. Today’s trans rights discourse evokes many of the same objections. Both sects shunned supposedly essential public rites, like standing for the pledge and burning incense to the emperor.

St. Augustine, whose City of God represents the most thorough attempt to theorize this civilizational shift as it was happening, even stepped temporarily into the role of Nikole Hannah-Jones to take a few swipes at Rome’s founding myths.

“The founder of the earthly city was a fratricide,” Augustine writes, and there was “a corresponding crime at the foundation” of Rome, “that city which was destined to reign over so many nations.”

Nor was the bishop of Hippo particularly enthused about Virgil’s great patriotic epic. In his spiritual autobiography Confessions, Augustine recalls that during his school days, he “was forced to memorize the wanderings of some fellow called Aeneas,” a story that “the more scholarly will admit is untrue.” (Other Roman Christians were kinder to the pius Trojan prince.)

The founding myth that mattered to Augustine began in a cave in Judea, not on a hill in Italy or inside the walls of Troy.

The Christian revolution triumphed. Julian the Apostate died acknowledging the victory of the “pale Galilean.” Flavius Stilicho burned the books that contained the Sibylline oracles. The last, bitter generation of Roman pagan elites was left to lament the fading of the “lyre of Apollo” and the “cry of the amorous nymph,” as one such character in Dorothy Sayers’ play Constantine puts it.

The difference is that in the fourth century, only one side was working to erode the foundations of their own society. In contemporary America, a dismissive attitude toward Saratoga, Valley Forge, Sam Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Common Sense, and all the rest is no longer the exclusive domain of the left.

“I don’t know anybody who’s not seventy who’s super into the American founding…none of us are particularly committed to it, frankly,” Declan Leary, a post-liberal Catholic and American Conservative editor, said in a recent interview. Older post-liberals like Sohrab Ahmari and Adrian Vermeule might not be as flippant, but they’d agree that America’s founding ethos leaves much to be desired. Benedict Option author Rod Dreher, who calls himself a post-liberal but isn’t quite ready to chuck the whole American project, endures a never-ending stream of criticism from the true believers. Dreher argues (naively, his detractors say) that the US Constitution still does an okay job of safeguarding liberty and that a Catholic integralist state might well turn tyrannical. Even this lukewarm expression of Americanism is enough to mark him as part of the problem.

To the progressives, the Founders are a clique of white, male, bigoted, mostly slave-owning one-percenters who acted primarily to preserve and expand their own privilege. To the trads, they’re a heretical lot of Deist Freemasons whose addlebrained Enlightenment theorizing led inevitably to drag queen story hour.

If these are the up and coming ideas on right and left, I’m not sure how the current regime survives. What comes next might still be called the American Republic, just as something called the Roman Empire persisted for over 1,100 years after Constantine’s conversion. There will likely be some points of continuity between the two.

Whatever the re-founded nation looks like, though, it will no longer draw its vital energy from the Spirit of ’76.