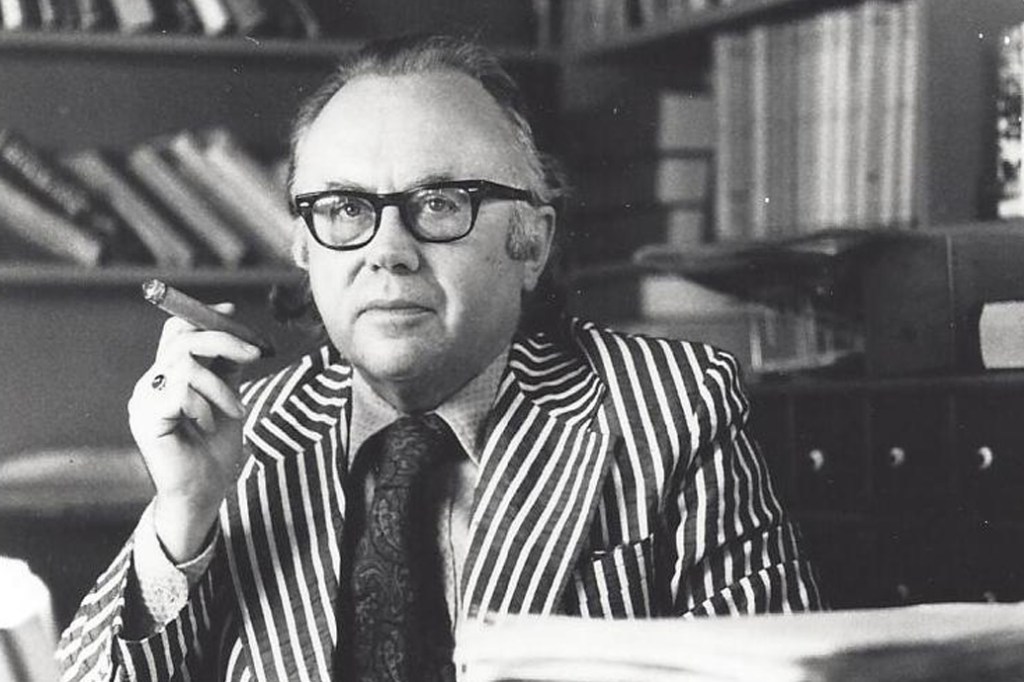

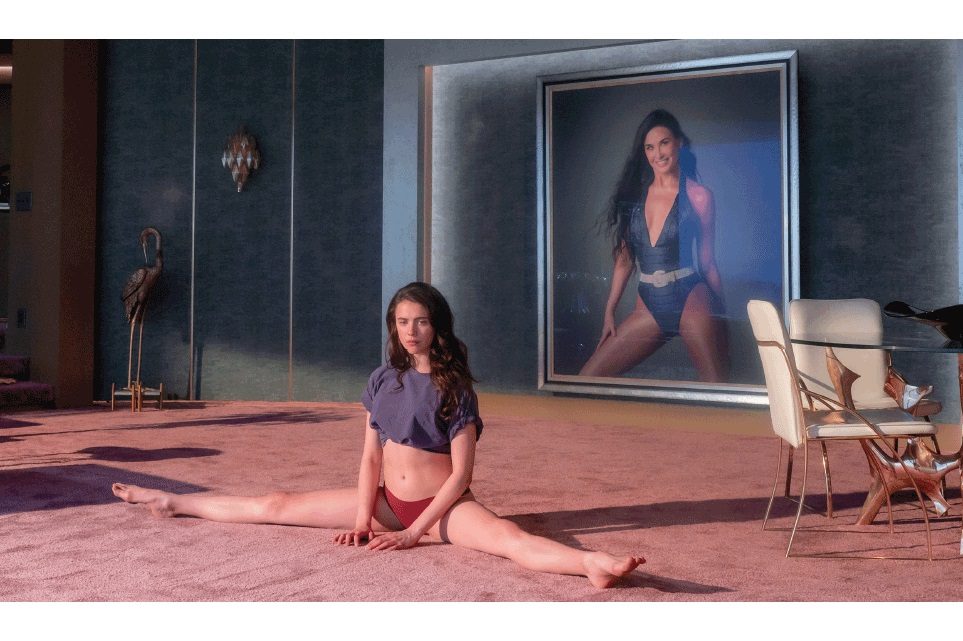

Russell Kirk’s novel Old House of Fear became a surprise bestseller when it was first published in 1961. First issued in hardcover by a small publishing house called Fleet, Old House quickly went through multiple paperback reprintings by Avon Books. Mary MacAskival, the red-haired love interest, has an increasingly tantalizing appearance on Avon’s succession of cheesecake covers. ‘Rich in atmosphere and intimations of impending doom… from the first muffled cry to the final midnight scream,’ declared the New Yorker of an edition on whose cover Mary sneaks around a Gothic portal in pink pajamas. ‘Wild excitement, sadistic violence. An “unblushing Gothick tale” and a good one,’ said Saturday Review, while a henchman grabs Mary’s wrist with one hand and chokes her with the other.

Old House of Fear sold more than all of Kirk’s other books combined, including 1953’s The Conservative Mind. Its royalties buoyed the Kirk family’s finances for years. Ghosts, literary and spectral, were a lifelong fascination for Kirk. Now as in Kirk’s own time, stories of horror and the supernatural are often disparaged as inferior to ‘quality’ realism. Kirk saw realism as ‘dreary baggage’, the ‘art of depicting nature as it is seen by toads’, a ‘dead-end street’ for the writer who ‘struggles to express moral truth’. In addition to his deep political understanding, Kirk was clairvoyant about the fate of the modern American novel.

Even in the new world of the streamlined Sixties, America was still haunted by tales of the old. Kirk appreciated what he called the ‘fearful joy’ of ghost stories. Such tales, which need not feature floating white sheets to be ‘ghostly’, formed a modern tradition that Kirk traced from Horace Walpole to L.P. Hartley. Kirk made sure to distinguish his ghost stories from the contemporary ‘flood of “scientific” and “futuristic” fantasies”’, which he called ‘banal and meaningless’. ‘For symbol and allegory,’ Kirk wrote, ‘the shadow-world is a far better realm than the hard, false “realism” of science-fiction.’

Kirk did not fear ghosts. He feared their death and their afterlife in myths and tales. In his scholarship and writing, he attempted their revival. In ‘A Cautionary Note on the Ghostly Tale’, an essay published in the Critic in 1962, he noted that the:

‘supernatural has attracted writers of genius or high talent: Defoe, Scott, Coleridge, Hoffmann, Stevenson, Maupassant, Kipling, Hawthorne, Poe, Henry James, F. Marion Crawford and Edith Wharton; and those whose principal achievement lies in this dark field — M.R. James, Algernon Blackwood, Meade Falkner, Sheridan Le Fanu and Arthur Machen. Many of the best are by such poets and critics as Walter de la Mare, A.C. Benson and Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch.’

Regrettably, Kirk went on, since ‘most modern men have ceased to recognize their own souls, the spectral tale has been out of fashion, especially in America’. An autodidact, Kirk called himself the ‘last remaining master of ghostly stories’. Unfashionable as his ‘decayed art’ may have become, ghost stories do not go unread. Beneath our rationalist feet there remains haunted ground. Hence the popular success of his supernatural fiction.

Kirk began publishing ghostly tales in the early 1950s in small periodicals such as Queen’s Quarterly, London Mystery Magazine and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Many of his stories have been anthologized several times over. The quality of his fictional prose and his interest in ghosts were not ancillary to his conservative mind. They were central to a Gothic sensibility which detected conservatism in the revenant spirits of America’s literary and cultural traditions. ‘Art is man’s nature,’ he wrote, quoting Edmund Burke, who also had doubts about the supremacy of rationalism. And ghost stories were Kirk’s nature.

‘Tenebrae ineluctably form part of the nature of things; nor should we complain, for without darkness there cannot be light,’ Kirk writes in ‘A Cautionary Note’. In Kirk’s tales, lingering superstitions battle against the false faiths of our age. Early stories, such as ‘The Surly Sullen Bell’ (1950) and ‘Ex Tenebris’ (1957), are darkly illuminating, with old believers escaping the clutches of New Age academics and conjuring up revenge against progressive urban planners.

Kirk was born in 1918 in the small town of Plymouth, Michigan, along the old Ann Arbor Trail leading to Detroit. He grew up poor in creature comforts but rich in books and stories. Graduating from Michigan State, he took a master’s degree from Duke and then, following service in World War Two, went to the University of St Andrews in Scotland, where he was the first American there to earn the degree of Doctor of Letters. A year later, Henry Regnery published his doctoral dissertation, updating Kirk’s title from ‘The Conservative Rout’ to The Conservative Mind.

Old House of Fear was published eight years after Kirk’s return to the States, when he was already known as a founder of the postwar American conservative movement. Duncan MacAskival is an Andrew Carnegie-like industrialist who wishes to return to his ancestral home in the Western Isles of Scotland. ‘Look at it all,’ he says of his ironworks. ‘I made it. And what has it given me? Two coronary fits.’ He quotes Wordsworth: ‘Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers.’

MacAskival hires Hugh Logan to travel to Carnglass and purchase the island and its castle, the Old House of Fear. The name is Gaelic, we learn; fir means ‘man’. On the island, Logan meets Mary MacAskival, the red-haired ingénue. Together they face off against Dr Edmund Jackman, a mystic who holds the island under mysterious control. Luxuriating in the maritime scenery, Kirk’s writing is possessed by a sense of place:

‘At six o’clock the Lochness steamed away from the pier toward the Sound of Mull. They crossed the Firth of Lorne; and then, to the south, they skirted the great rocky mass of Mull, while the wild shores of Morven frowned upon them from the north. Several islanders were among the passengers, and for the first time in years Logan heard the Gaelic spoken naturally, that beautiful singing Gaelic of the Hebrides. It went with the cliffs, the sea-rocks, the ruined strongholds of Mull and Morven, the damp air, the whitewashed lonely cottages by the deep and smoothly sinister sea.’

In the last year of his life, Kirk spoke about ghosts at length from Piety Hill, the ‘ancestral home’ in Mecosta, Michigan that he came to occupy after marrying Annette Courtemanche in 1964. Though he was convalescing from bronchitis, he gathered a small audience in order to tell ‘some ghostly tales’. Before the reading, he elaborated the ‘true narration’ of the ghosts in his life and the life of his family.

Kirk converted to Catholicism when he married, yet he maintained much of the mystical sensibility of his ancestors, followers of the theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. A New York lumberman from the ‘burnedover’ country of the Finger Lakes, Kirk’s great-grandfather came for the trees of Michigan and brought Swedenborgian faith with him, building a spiritualist church across from his settlement in Mecosta. After the church burned, the family conducted séances in their home.

‘Mine was not an Enlightened mind,’ Kirk famously said of himself. ‘It was a Gothic mind, medieval in its temper and structure. I did not love cold harmony and perfect regularity of organization; what I sought was variety, mystery, tradition, the venerable, the awful.’ Kirk saw the modern age at a time-traveler’s remove. He surveyed the world with idiosyncratic fascination, looking for lost connections between the timely and the timeless. In his writing, he was his own poltergeist or ‘rattling spirit’, making critical noise to remind us of the lost ties and subterranean spirits just below the rubble at our feet and the theories in our heads.

Kirk’s third eye saw through the many false beliefs of the modern age: ‘The primary error of the Enlightenment was the notion that dissolving old faiths, creeds, and loyalties would lead to a universal sweet rationalism. But deprive man of St Salvator, and he will seek, at best, St Science.’

This is why Kirk’s haunted fiction, like his dim view of modernity, continues to speak to us. The more we look to the ‘variety, mystery, tradition, the venerable, the awful’ in his life and work, the better we appreciate his Gothically conservative mind. Kirk believed in ghosts and believed in people who believed in ghosts. He also believed in people who believe in ghost stories. He would not definitively say whether ghosts were objective or subjective phenomena, forces of the universe or the human imagination:

‘Can we imagine a human soul operating without a body? You and I are just a collection of some electrical particles, held in suspension temporarily. We aren’t really solid at all. Can there be a collection of such particles in a different form that can occasionally manifest itself? Nobody knows.’

When we conjure Kirk’s legacy, we too summon a revenant spirit. Fiction and fact, subjective belief and objective existence, were fluid dynamics in Kirk’s mind. He believed in the life of the dead, in the afterlife of the soul and in the imbuing of the soul with the living spirit of a culture. His beliefs haunt us still, just as they haunt the Gothic landscape of Old House of Fear.

This essay is an edited version of James Panero’s introduction to the new edition of Old House of Fear (Encounter Books). This article is in The Spectator’s December 2019 US edition.