The trailer for David Fincher’s latest movie, the hitman thriller The Killer, promises that admirers of one of cinema’s most talented directors will be getting their money’s worth, whether they see it during its theater release or wait for it to premiere on Netflix (which paid for it), just as they did Fincher’s previous film, Mank, and his serial-killer series Mindhunter. There will be a lead performance by Michael Fassbender — returning from several years away from the big screen racing cars — that will, as usual, combine icy charisma with brute physicality. There will be impressively gloomy cinematography, courtesy of Erik Messerschmidt. No doubt the screenplay, from Fincher’s Se7en collaborator Andrew Kevin Walker, will offer a mixture of bone-dry quips and gloomy musings on an assassin’s lot. And, naturally, the soundtrack will be wall-to-wall Smiths hits.

Sorry, what? Of all the music that one would expect to accompany the violent study of a man in existential crisis, the songs of the cult Manchester band would not be most people’s first choice. Yet Fincher, speaking at the film’s premiere at the Venice Film Festival in September, defended his decision, on the grounds that the music — specifically one of their finest hours, the gloomy “How Soon Is Now?” — functioned as a kind of mixtape for Fassbender’s anonymous killer, and that this decision was “amusing and funny.”

The balance between horror and hilarity has often been a hallmark of Fincher’s work. Whether it’s Kevin Spacey’s perfectly judged one-liner toward the close of Se7en, when his evil masterplan is about to come to fruition but a dead dog is spotted in the desert — “I didn’t do that” — or the moment in which Stellan Skarsgård’s villain prepares to torture and murder Daniel Craig’s protagonist in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and puts on Enya’s “Orinoco Flow” to get himself in the mood, there are many moments that feel both subversive and deeply inappropriate throughout his filmography, reflecting Fincher’s warped sense of humor as well as his fascination with heightened psychological states. After all, when you’re on the edge, anything can come to seem horrible or hilarious, so why not have both co-exist?

Since his career began three decades ago with Alien 3, a film that went through a notoriously troubled production process and has now been disowned by its director (he has called it “a truly fucked-up situation”), Fincher has occupied an unusual, even unique place in contemporary Hollywood. With the exception of his elegant but somehow anonymous aging-backwards romance The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, his films take grim delight in delving deep into the dark recesses of the human psyche, exploring the ways in which people do unspeakable things to one another — for cash, for kicks or because, on some twisted level, they feel they have to.

Compared to his fellow A-list directors Steven Spielberg and James Cameron, whose films generally offer an optimism about humanity (or, in Cameron’s case, the blue-skinned inhabitants of Pandora), Fincher’s worldview is bracingly nihilistic: life sucks, people will betray you, we’re all going to die horribly and the best thing you can do is to stamp on the sucker below you on the ladder before he, or she, gets a chance to pull you down off it instead. Sometimes, this manifests itself in simple violence, but at others, as with his biographical drama Mank and the Facebook film The Social Network, the assault is all psychological. For Fincher, contemptuous treatment of your fellow man is merely a way of life. What else can you expect?

Unsurprisingly, this has not led to vast financial success: his biggest hit, Gone Girl — a beautifully executed and often hilarious exercise in misanthropy masquerading as a mystery thriller — made around $370 million at the box office, which is an impressive-enough number but considerably less than what, say, the rather sunnier Mamma Mia pictures made. And there have been plenty of flops or underperforming pictures along the way — the much-acclaimed serial-killer procedural Zodiac, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (marketed, at his insistence, as “the feel-bad movie of Christmas”) or, notoriously, Fight Club, which we shall return to in a moment. Yet his misanthropy has never seriously damaged his career or reputation. Although there are countless mainstream projects he was attached to that never came off, ranging from his version of Mission Impossible III to a big-budget adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Fincher has progressed from cult hit to cult hit, maintaining his integrity in the process. Even Panic Room and Benjamin Button, his two most obviously mainstream pictures, contain enough weirdness and off-kilter perversity to enthrall and shock audiences forever.

With the exceptions of Benjamin Button and — more surprisingly — The Social Network, Fincher’s films have been exclusively R-rated and aimed at adult audiences, usually male ones. Which is not to say that he isn’t a superb director of women: it’s notable that some of the best performances in his films — Rosamund Pike in Gone Girl, Rooney Mara in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo or Jodie Foster in Panic Room — come from their female leads. But ever since the enormous success of Se7en, he has remained a director who is much-loved by an enthusiastic and vocal cult audience, who treat him like a rockstar at his public appearances.

Like Quentin Tarantino and Christopher Nolan, two other “bro” directors whose most famous films have assured them a male following for life, Fincher has fanatical admirers who will not hear a word against him and who scornfully disparage those who are seen as imitators or plagiarists. Matt Reeves’s excellent The Batman was criticized in some corners as little more than a rip-off of Se7en, a fair accusation, although it ignores the considerable artistry and skill Reeves brought to his film. Still, he’s no David Fincher, even though his movie made more than double what any of the older filmmaker’s pictures have grossed.

The reason Fincher is so beloved, even dangerously so, is simple: Fight Club. A commercial failure on its release in 1999, lambasted by many influential critics, including Roger Ebert (who called it “the most frankly and cheerfully fascist big-star movie since Death Wish”), it stands as one of the most subversive and daring pictures ever to have been released by a major studio, in this case Twentieth Century Fox.

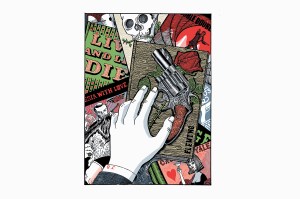

On paper, it is a celebration of machismo, spearheaded by Brad Pitt’s charismatic Tyler Durden — the avatar of any number of bro influencers like Andrew Tate and Jordan Peterson — that delights in a combination of brutal violence and anti-consumerist, anti-capitalist sloganeering to make its point, even down to an ending which uncannily pre-figures the destruction of 9/11, soundtracked by the Pixies’s “Where Is My Mind?” Where indeed? Fight Club is currently ranked the twelfth greatest film of all time on IMDb, ahead of It’s a Wonderful Life and Silence of the Lambs. Its iconic poster adorns innumerable teenage bedrooms; even its title is shorthand for a flashy machismo that has inspired its present disciples, many of whom were too young to see the film on its initial release.

I have never really changed my initial opinion that it is the blackest of black comedies, a Graduate for the turn of the millennium. There are overtones of everything from Withnail & I to mid-Seventies Woody Allen in its superbly calibrated lunacy, anchored by Edward Norton’s adroit performance as the anonymous lead, “The Narrator,” whose repressed alter-ego, the swaggering Durden, comes to represent the Jekyll-and-Hyde duality of the contemporary man, the office drone who secretly longs to beat his colleagues, bosses and friends alike into a pulp at the weekend. It is very funny, beautifully observed and often wildly misunderstood: like many of Fincher’s other films, it not only rewards repeated viewing, but positively demands them to get the most nuance out of its skillful, witty provocations.

It is hard to know whether The Killer will be a commercial hit, given that since its stars will be unavailable to promote it and it’ll be on Netflix after a few weeks anyway, only Fincher fanatics are likely to be queuing outside their local movie theaters to see their idol’s latest exercise in blackly comic wish fulfillment. Yet at a time when distinctive and interesting voices are being silenced in Hollywood, Fincher’s continuing ability to challenge, provoke and entertain is a marvel. His admirers may lurk on Reddit to obsess over details others find irrelevant, but there can be little doubt that this most accomplished of filmmakers may yet have the last laugh. The rest of us can only share in that particular mirth.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2023 World edition.

Leave a Reply