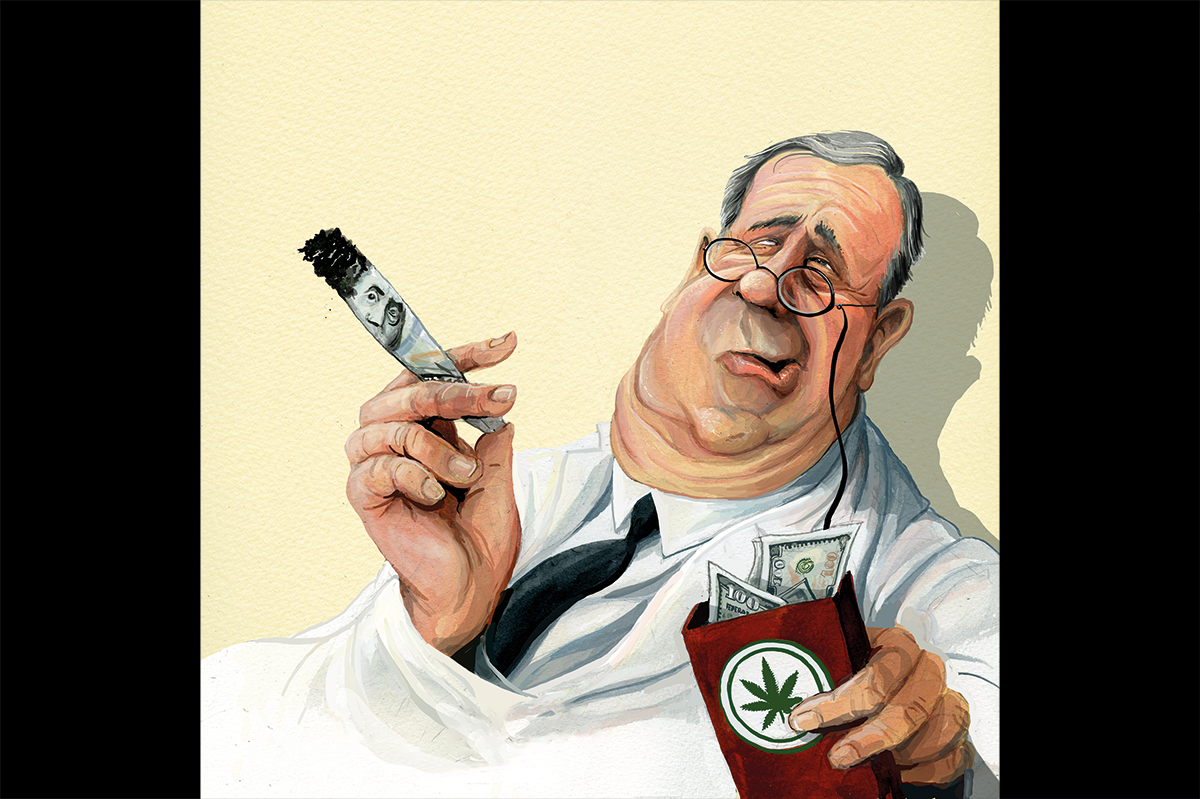

‘You’re never alone with a Strand,’ went the misbegotten cigarette advertisement of 1959. But smokers often smoke to be alone. In its heyday, smoking was not just a means of escaping the dead hand of sociability: it briefly cast a smoky veil over the unbearableness of life. No wonder smoking was especially popular among the working poor: snatched moments of peace and quiet were breathing spaces from otherwise unremitting grind, noise and worry.

True, smoking had risen in popularity during World War Two as a means of brokering sociability. After the war, its continuing vogue was fueled by an opposite impulse — to disconnect from the hell of other people. Like masturbation (which David Vincent unaccountably omits from his book), smoking is a solitary pleasure; on occasion, it is also acceptable among others.

Vincent regards smoking as the defining example of abstracted solitude. It’s no coincidence that the cigarette packet is roughly the same size and shape as today’s fetish object, the smartphone. But the smartphone is also the culmination of another kind of solitude. The penny post, newspapers, telephone, film, television, the internet and iPhones have offered networked solitude, keeping us in touch with distant people while letting us remain apart. The diabolical genius of smartphones allows us to be simultaneously abstracted and networked: present and absent at once, solitary and gregarious at will.

Such paradoxes abound in this beautifully written, nuanced and now topical history. Do we have the right stuff to be alone without being lonely? Our ancestors cultivated solitude as a respite from the world, to reform character in prison or to commune with God in retreat. Perhaps modern self-isolators can learn from their examples.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Very few of us, though, have the mental resources of Hertfordshire’s leading Buddhist hermit, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo (born Diane Perry). She spent 12 years in a 10’x 6’ Himalayan cave, surviving temperatures of -31F. Despite such propitious circumstances for escaping human fatuousness, she didn’t achieve moksha. We self-isolators haven’t chosen to be alone. Like prisoners in solitary confinement, whose shadowy history Vincent traces here, we are stuck in circumstances to which we’re temperamentally unsuited.

Rather than Buddhist nuns, we better resemble Don Martin Decoud, the plump dandy journalist of Conrad’s Nostromo. All of Decoud’s reserves of worldly irony and skepticism are useless once he is marooned on a desert island. Despairing, he fills his pockets with silver bars and, Conrad writes, is ‘swallowed up by the immense indifference of things’.

Even before COVID-19, many yearned, like Garbo, to be alone. In the early 20th century one percent of Britons lived alone; by 2011, 31 percent did, many of them finding self-fulfillment rather than a motive for suicide. The Guardian columnist George Monbiot, though, sees in such figures an ‘epidemic of loneliness’. We have lost, he claims, what is essential about humans, namely connectedness.

Vincent paints a more nuanced picture. To some, living alone had always been preferable. After World War Two, it became more feasible, too. Loneliness arises, Vincent reckons, when we are marooned by bereavement or when investment in social and health services declines. One definition of loneliness is solitude continued further than intended: what started as self-liberation becomes a life sentence.

Vincent insists on what Monbiot misses: how essential it can be to remove oneself — if only for the length of a cigarette or a game of Candy Crush — from the hard labor of sociability. Hence the popularity of Sylvain Tesson’s memoir Consolations of the Forest, about a man who lives as a hermit in Siberia for six months. Hence, too, the allure of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking, in which Susan Cain suggests that the noisome extroverts yucking up their nothingy conversations on buses have their parallel on Twitter. How lovely to escape them — ideally by withdrawing into solitude to read. Vincent’s book is a treasurable flipside to the sound and fury that historians usually focus on, a quiet history of solitary activities: walking, fishing, gardening, needlework, embroidery, stamp collecting, crossword-solving, dog-walking, jigsaw puzzles, DIY and reading. But the author is always sensitive to how recreational solitude risks becoming a form of conspicuous consumption for wealthy eccentrics. Not all of us can afford to circumnavigate the globe single-handed.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”][special_offer]

He’s attentive, too, to how those recuperating from work or domestic labor have long sought solitude. When there is no nature with which to commune, silently staring into the middle distance in the park with cigarette and dog as foil may not be as mindless as it initially looks.

Compare such seeming mindlessness to today’s cult of mindfulness: ‘solitude tailored to late modernity — eclectic, privatized and readily commodified as an avalanche of print, supportive objects, digital media and courses that flood into the market’. The austere virtuosi of solitude — Wordsworth wandering lonely as a cloud, Tenzin Palmo meditating in her Himalayan cell — needed no such fripperies.