Odysseus is tossed on the sea when he notices a rock and clings to it. “As when an octopus is drawn out of its lair and bits of pebble get stuck in its suckers,” says Homer, “so his skin was stripped from his brave hands by the rock.” There is such elegant tricksiness in that simile.

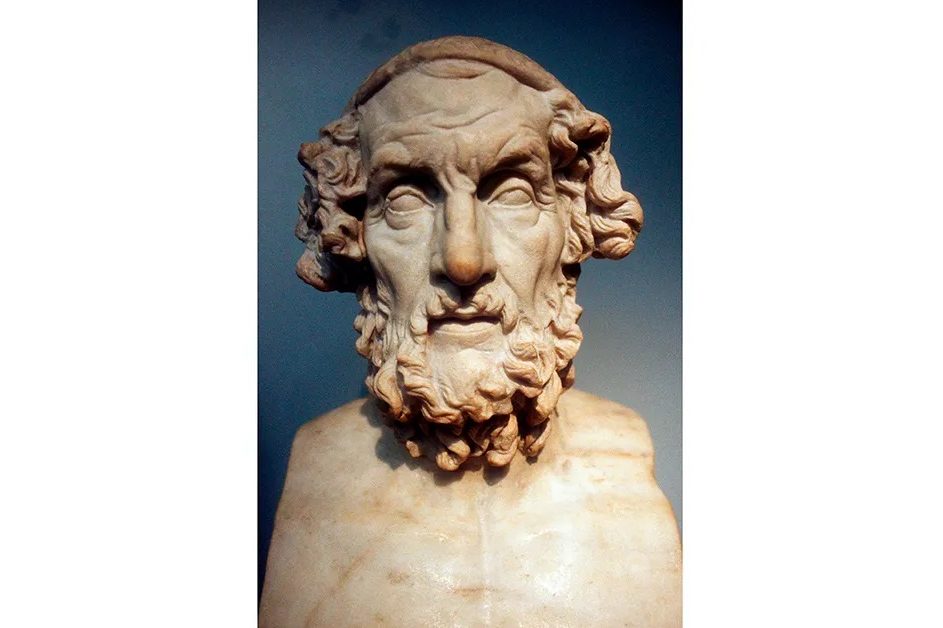

Homer still sits at the apex of western literature thanks to the beauty and influence of his verse. Robin Lane Fox has been teaching the epics for fifty years and studying them for many more. His lifelong fascination with the texts has bred a sort of feverish passion in him that makes him declare Homeric poetry to be “beyond us” today (he is probably right) and without equal anywhere in the world, except perhaps in the books of Tolstoy (who is surely still inferior).

In Homer and His Iliad he offers a close-reading celebration of the elder of the two epics and a bold reassessment of how it came to life. In the reassessment part, the book feels less like a willful provocation than a throwing down of the gauntlet by a seventy-six-year-old with nothing to lose. Lane Fox writes less with hope than bardic omniscience that his book will become a landmark in Homeric studies.

For Lane Fox, Homeric poetry is ‘beyond us’ today and without equal anywhere in the world

First, the celebration. His extended engagement with the poem yields observations that will have passed many other readers by. I had not noticed, for example, how frequently characters in the Iliad use the word “always” of each other’s actions to indicate habitual behavior. Hera says that Zeus always delights in making plans behind her back and, according to Agamemnon, Achilles always finds pleasure in strife. Nor had I taken in that there are three sets of divine horses in the poem, two on the Trojan side, one on the Greek. We tend to remember only Achilles’s talking horse.

Even fewer readers will have appreciated that the Iliad contains dialogue by seven different women. Lane Fox is emphatic on the prominence of female voices. Do we detect some irritation on his part with the explosion in fiction marketed as “finally giving Homeric women a voice?” Yes, he says, Chryseis and Briseis remain silent, but that is “not because Homer belittles women but because they are enslaved girls and have no agency in what happens.” Three goddesses, by contrast, do speak, because their words shape the narrative. The enslavement of Troy’s women, dramatized so well by Pat Barker, postdates the events of the Iliad and is not simply passed over. Women make choices, though many would argue that Helen’s “elopement” with Paris was not her choice, as Lane Fox states, but rather that of Paris.

An appreciative commentary on the poem occupies the final two-fifths of the book. The first three-fifths are dedicated to Lane Fox’s hypotheses and are necessarily more controversial.

The consensus among most scholars now is that Homer was not one person but many. The theory that “the Greek peoples were themselves Homer,” as advanced by the Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico in 1730, gained momentum in the past century following the realization that the epics were composed orally and preserved for generations by performing bards prior to the rediscovery of the art of writing in Greece in the 8th century BC.

Lane Fox does not accept the idea of many Homers. He disagrees with those who argue that the Iliad is a patchwork of preserved poems, or “a rolling snowball,” which grew through the contributions of the various poet-performers, like a “house built upon a plan comparatively narrow and subsequently enlarged by successive additions,” as the historian-banker George Grote put it. For Lane Fox, Homer was not plural; he was a man.

His most creative arguments are adduced against the theory of the poem as a patchwork. If the Iliad was assembled in parts, he asks, how would it have such a carefully calibrated sense of time, with some days compressed and others expanded upon? It is difficult to imagine a succession of poets foreshadowing Achilles’s early death in such a gently building and consistent manner.

Details in descriptions of the flora and fauna also suggest to Lane Fox the presence of one man in the landscapes of the Troad. Drawing on his horticultural expertise — he is the gardening columnist for the Financial Times — he identifies the “yellow crocus, “hyacinth” and “lotus” watered by Zeus and Hera’s lovemaking with Crocus gargaricus, scillas and a form of clover.

His Homer was an illiterate man living in western Turkey or the eastern Aegean in the mid-8th century BC. He had practiced composition-in-performance since boyhood and had honed the technique of revising his work while rehearsing it over and over prior to his first official performance, which might have been at a religious festival. The work caught on, and eventually he dictated it to a scribe, ensuring its survival.

One has to wonder what would have prompted an illiterate poet to take this major step. Did he not share the faith of his characters in the immortality of song? Did he recognize that writing was the future? Or was it simply a case that the poem had become too complex and unwieldy to pass down any further? A performance of the Iliad would have taken at least three days.

There is no way of proving the theory of a single Homer right, but there is also no way of proving it wrong. The romance of a solitary genius is as likely to repel scholars as it is to appeal to readers in our age of AI. Rather like Adam Nicolson’s Why Homer Matters, which proposes a peculiarly early date for the poems, the impossibility of verifying the hypothesis does little to detract from the fascination of Lane Fox’s book.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.