As a little boy, Luke Turner, like so many other little boys, was fascinated by World War Two. He used to spend hours carefully making Airfix models of warplanes, and his favorite haunt was the Royal Air Force Museum in Hendon, a suburb of North London. Men at War, his second book, is an attempt to explore and explain both this interest and his own sexuality (he is bisexual, with a female partner), in response to what he sees as the dominant, jingoistic attitude propagated via general British cultural discourse.

He claims that we do not see those who fought as individuals, but as clipped, heroic avatars, like Captain Sir Tom Moore, who raised millions of pounds for NHS charities during the lockdowns: dignified, silent, brave. Could we, Turner writes, “countenance the idea of the veteran hero Captain Tom … cracking one off under itchy blankets?” Thus he delves into the private lives of a collection of mostly homosexual and bisexual men who witnessed those turbulent times.

Turner’s essential thesis is that the war opened up a brief time of sexual liberation for men, which the postwar world quickly closed off in prudish horror. We meet a rag-tag collection of people, some already familiar, some not, deployed to show that life in the army (and outside of it) offered a range of sexual possibility, despite the mores of the time being actively anti-homosexual.

Some ostensibly straight men, Turner writes, were happy to find solace with another fellow; others (he muses at length) were showing their true bisexuality; still others were fully homosexual. Peter de Rome (who made no secret of his homosexuality, going on to produce gay pornographic films) can be found pleasuring himself and a Mauritian soldier near Bayeux. A gay man (who seems to have been largely accepted by his regiment) is asked to indulge his sergeant, who wakes one day with an enormous erection. The artist Colin Spencer (who also made no secret of his inclinations) chose to volunteer for the Medical Corps to check men for venereal disease so that he could see “a lot of cocks.”

Well, if that floats your boat, though there might have been other ways to go about it. A pilot called Ian Gleed writes a novel in which he refers to a fiancée called Pam; his family are amazed, having never heard of her; it is, in fact, a disguised version of his much younger male lover, with whom he goes sailing, and takes out in a two-seater Tiger Moth aircraft for a treat. Nobody seems to mind very much. A heterosexual Essex man visits a barber in Cairo, where he’s shown a “girly magazine.” The proprietor then arranges for him to be masturbated under the barber’s sheet by a “young lad.” We are not told what happened to the sheet.

Turner ruminates on connectivity: “I imagine atoms of a German Heinkel or Junkers from the Cowley dump melted down to become an Avro Lancaster only for that aircraft to be shot down over Germany, collected as scrap metal there, the process beginning again.” There are plenty of tidbits, such as the propaganda efforts considered by the British, including “a doctored … photograph of Hitler with a giant circumcised penis to be dropped by RAF bombers over German cities.” They didn’t use it, in the end.

Turner, rather refreshingly, is non-judgmental in his assessments of the characters he explores. Of Michael Burn, a young man who initially supported Hitler (but immediately changed his mind), he asks: “Can we condemn him for being swept away in the steely euphoria of Nuremberg? None of us is as far from being seduced by these totalitarian aesthetics as we might like to think.” Similarly, he doesn’t want readers to make the men he writes about into gay icons, but simply to recognize their individual feats of bravery and conscientiousness as being part of the general war effort: as facets of masculinity and femininity, rather than as one or the other. This strikes me as being sensible. He is also good on the internal struggles of gay and bisexual men, something which he himself suffered through as a teenager.

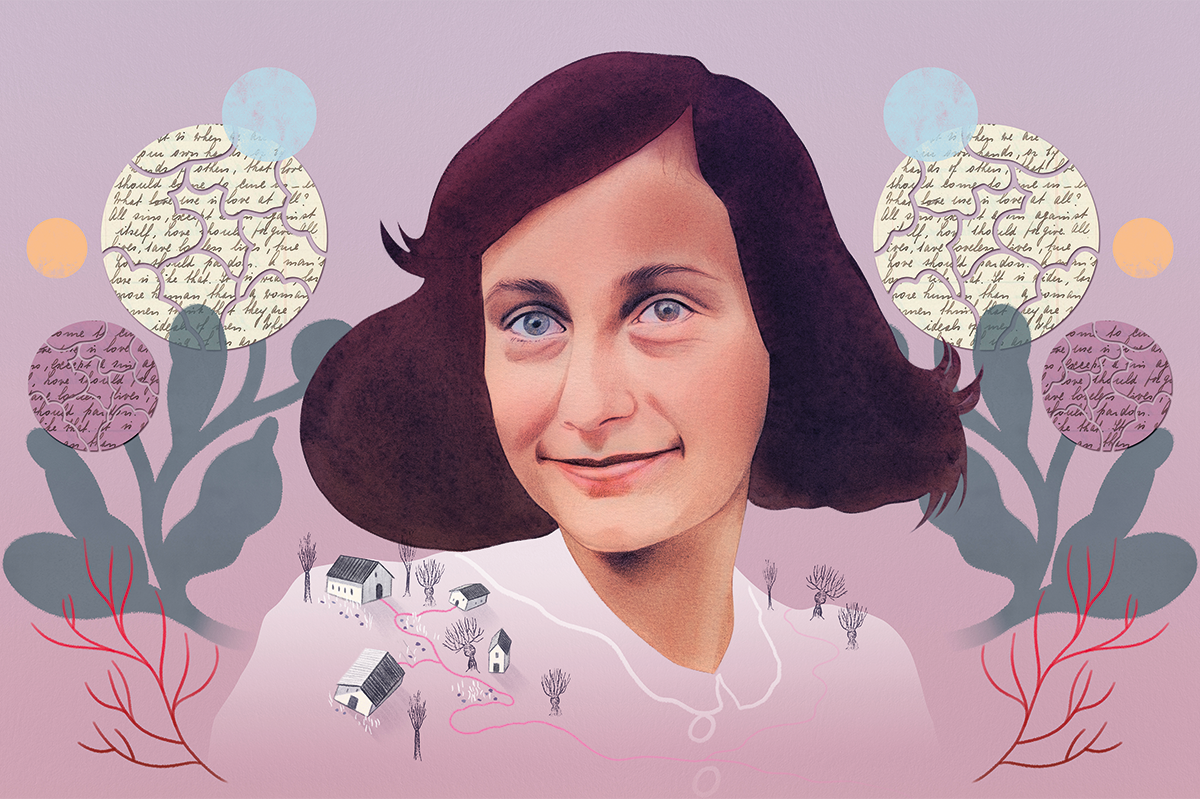

There is, however, a potentially more thought-provoking family memoir inside these pages, yearning to get out. Turner’s grandfather, Percy, is discharged from his post in Africa — possibly because he refused to take a bribe from the locals, and was consequently beaten up. “He came around lying next to the coffin that was being prepared for his burial, a shock that was enough to make him cling to life.” Had he not, there would have been no Turner. His other grandfather, Edwin, was a conscientious objector, something which caused the young Turner much grief. And he writes beautifully about his own relationship with his partner and young son, whose family were Jewish and suffered terribly.

But this points towards a more complex, difficult subject, of which there are many at hand, though Turner skates over them. How much younger, for example, was Ian Gleed’s “young friend?” How old exactly was the “young lad” that masturbated the Essex boy? The focus on the experiences of men means that the tendency of soldiers to rape women in war (not to mention the proliferation of prostitution, with women selling themselves for tins of Spam, and fathers selling their daughters for food) is only glanced at.

One of the major issues with this book is that not only do we already freely have all the primary sources that Turner mentions (Julian MacLaren-Ross’s short stories, Patrick Hamilton’s novels, not to mention the films and artwork produced by the people he studies, although I suggest that you do not Google Peter de Rome if you are in a public place) but that there are plenty of other fictional and poetic works which show that life in the army was not everything myth would say it was.

You only have to read Siegfried Sassoon (himself quite openly bisexual), Wilfred Owen, Evelyn Waugh, Henry Green and Joseph Heller (for a start) to see that not only were individual soldiers more complicated than one might assume, but also that sexualities were not monolithic. Even the children’s-book hero, flying ace Biggles, has “effeminate hands.” Postwar, we have the Alms for Oblivion sequence by Simon Raven, which centers homosexual characters, not to mention Mary Renault. And of course, ever since the ancients, we have been used to military male-on-male relationships: Achilles and Patroclus, Alexander and Hephaestion; the Sacred Band of Thebes (150 pairs of male lovers); Hadrian and Antinous and so forth. Times change, but men don’t, and ideas of masculinity and martial prowess have been in flux for centuries.

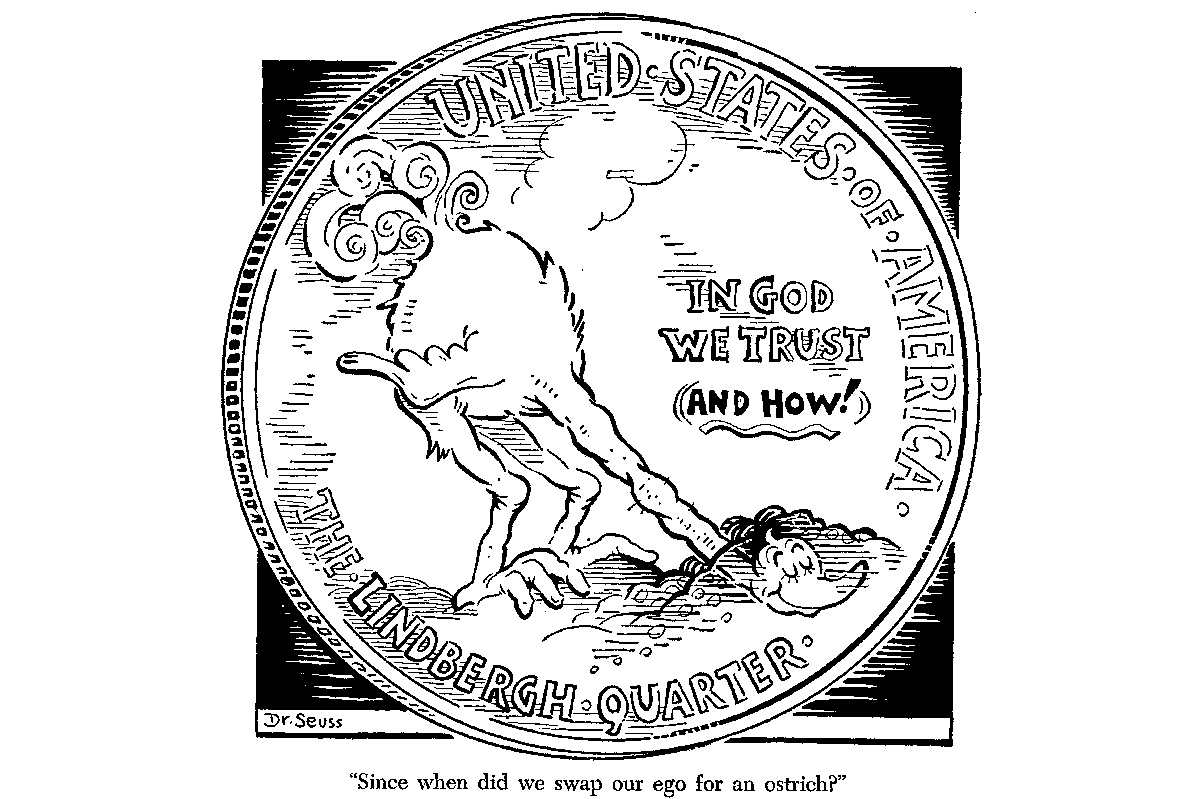

Turner is right when he says that in Britain we tend to keep alive a memory of our indomitable spirit during the war, and that the tone of our remembrances likes to emphasize how alone we were against the Germans, like Asterix and his village pitted against the Romans. We picture Buckingham Palace being bombed, so that finally the king and queen can look the East End in the face.

We think of Churchill and his cigar, dressing gowns and whiskey. I think of my grandparents, going out to dances in London on leave during the Blitz, dodging from party to party while bombs fell around them. But Turner underestimates our ability to distinguish between national myth and complex reality. You can imagine Captain Sir Tom Moore both as a hero and as a human.

This is an earnest book, and Turner seems to have a genuinely thoughtful and open approach, but ultimately it tells us nothing new, being rather a hodge-podge of cultural history, memoir, biography, sexual exploration and random musing. Instead, it is far better to focus on Turner’s final message as he looks at his son, “smiling, content … I hope that he will never have to face the outrageous metal of war, to be asked to kill or be killed.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2023 World edition.