A great writer must be prepared to risk ridiculousness — not ridicule, although that may follow, but the possibility that the work will collapse into some or other version of nonsense. If it doesn’t, though, it is precisely the elements that flirt with disaster that will likely make it both superficially distinctive and artistically substantial.

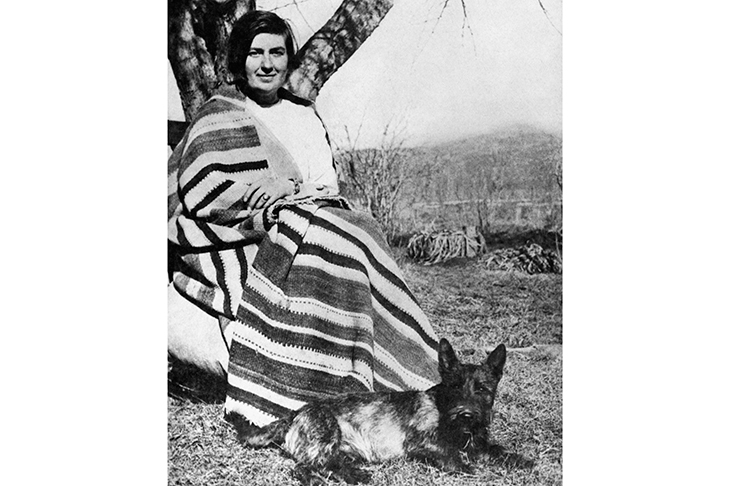

For the novelist and memoirist Rachel Cusk, whose most recent creation, the ‘Outline’ trilogy, attempted a savage blending of the two forms, risk comes frequently in the form of sailing dangerously — and, for her admirers, thrillingly — close to the parodic. Second Place, which in bare-bones description tells of what happens if you invite an artist into your home, ‘owes a debt’ (the author’s words, in an afternote) to Mabel Dodge Luhan’s Lorenzo in Taos, an account of D.H. Lawrence’s stay at the artists’ colony that the author had established in New Mexico. Written in 1932, many years after the visit, it is a portrait not only of Lawrence, but of Luhan, and of their tricky relationship. Now, of course, Luhan is a footnote in literary history, the fate of so many patrons of the arts, and of so many women who formed attachments to Great Male Artists.

Cusk’s version of Mabel — ‘M’ — is not quite the wealthy dilettante, her artistic enthusiasm crudely masking sexual and social appetites, that the caricature of such women has often relied on. But she is a bit. She lives in a marshy, pastoral idyll with her second husband, Tony, a largely silent, reliable, intuitively supportive type, a dab hand at mending fences and growing veg. Aware that his wife needs occasional injections of artistic and intellectual life, he helps to create a ‘second place’, a whitewashed, wood-floored cabin with enormous windows that sits in a glade on their property, and to which creative types come sporadically to create. It’s not all the life of the mind, of course; M is quick to hang curtains when she comes across a musician frying eggs, starkers.

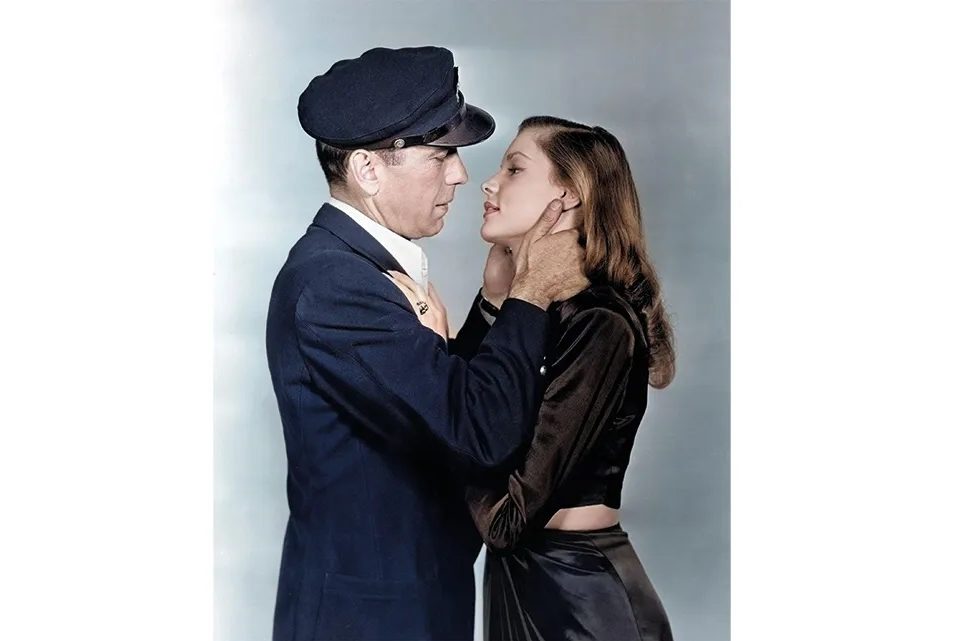

Onto this scene comes ‘L’, a painter whom M credits with changing the course of her life, including quitting an unhappy marriage. Years earlier, wandering the streets of Paris, she chanced on an exhibition of his, and its impact never left her. After a few false starts, she finally succeeds in persuading L to trade the tropical islands and intense cityscapes of his peripatetic, freeloading life for a summer in the marshes.

He is, of course, horrible. He arrives with an unannounced companion, a much younger woman who finds fault with the thread count of the sheets and offers to help M disguise her gray hair. He refuses to play ball and sip cocktails around the fire in the evening, chatting about art. He refers disparagingly the ‘little books’ that M writes, and likes her daughter far more than her. Worst of all, he asks everyone to sit for him except M herself.

This is the novel’s surface: a group of unbearable people cavorting in Arden, like refugees from an Iris Murdoch novel. The entire narrative is framed as an episode recounted years later to ‘Jeffers’, a friend of M’s, in the manner of a Victorian fireside tale. The literary echoes — not necessarily specific, but a gradual accretion of the recognizable, the clichéd — never stop coming.

But that is not all there is. Bubbling continually to the surface are M’s agonizingly raw reflections on selfhood, motherhood, desire, creation and reality. There is the immense cruelty that she has suffered — or perceives herself to have suffered — throughout her life: a history of slights, criticisms, lack of love. There is an extreme ambivalence toward the body, towards beauty and physical ease; and a concurrent lack of surety about mental and emotional endeavor. Investing some kind of desire in L’s proximity, M instead succumbs to:

‘a feeling of abjection, within which there was an illogical sense of hope. I wanted him to be more than he was, or to be myself somehow less than I was, and because I wanted those things my will was aroused.‘

Later, she tells us that it is her will that means she is ‘always straining to make everything how I wanted and thought it should be, to make it conform to my idea’ — as, she also notes, an artist does.

This is one of M’s more accessible meditations; quite often her descriptions of her thoughts move from the abstract to the abstruse, and there is a sense that the reader is repeatedly placed in the position of an old-school nanny who might tell her to go for a long walk and buck herself up. Were we to do that, though, we would miss this extraordinary exchange between the id and the ego, this fearless examination of the psycho-drama that plays itself out within us, making fools of us all.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.