In April, the Pet Shop Boys, pop music’s most influential and beloved synth-pop duo, returned with a new album, Nonetheless. The British pair could hardly be described as wildly prolific, having released a comparatively meager fifteen albums since their debut Please in 1986. (Their one-word titles usually contain some oblique joke or other; the act’s singer Neil Tennant once remarked that the idea for the first LP was that it amused him that a record buyer would ask for the “Pet Shop Boys, please.”) Yet one reason for this relatively sparse output is that they take a painstaking amount of time to ensure not only that each of their albums is polished to perfection, but that it is existentially different from their previous release.

If there is such a thing as a “Pet Shop Boys” sound, hommaged or ripped-off by countless other acts, it has to revolve around three ingredients: Tennant’s distinctive tenor voice, Chris Lowe’s four-to-the-floor electronic beats and, more often than not, lavish orchestration, a trademark of the band since the Eighties. The single that they returned with in February, “Loneliness,” was a perfect encapsulation of all three, complete with Tennant’s inimitable, shrugging lyrics that nod to such great English poets of miserabilism as Philip Larkin and John Betjeman. There are relatively few bands that would begin their comeback single with the lines “There is a better fight / A cause close to my heart / The struggle against loneliness / That’s tearing you apart,” followed by making an allusion to Ringo Starr’s downtrodden appearance in the film A Hard Day’s Night. This represents the Pet Shop Boys in microcosm: wit, allusion, innovation and a sly sense that the joke, such as it is, is on the listener.

Nonetheless came four decades, almost to the day, after the release of the first version of what would become their breakthrough hit, “West End Girls.” The song, produced by hi-NRG innovator Bobby Orlando, was a floor-filler in the predominantly gay clubs of Los Angeles and San Francisco, although it is doubtful that too many of their patrons were as impressed by Tennant’s high-flown allusions to “The Waste Land” as they were by the then-incongruous sound of a white, middle-class Englishman in his late twenties rapping — and, what’s more, doing it convincingly and tunefully.

It would take a while before it was re-recorded and released in Britain, but when it finally came out in late 1985, it slowly built word of mouth and eventually reached number one in the singles charts, after their Thatcher-baiting earlier single “Opportunities (Let’s Make Lots of Money)” failed to advance beyond the not-so-dizzy heights of 116. It was somehow typical that the B-side of “Opportunities” was “In The Night,” a song that dealt with a French World War Two subculture, les Zazous, whose apathetic approach toward everything apart from fashion and music allowed them to ignore the horrors around them. Tennant’s lyric muses that “there’s a thin line between love and crime / And in this situation / A thin line between love and crime and collaboration.”

These were not the concerns of, say, Duran Duran or Bananarama, and marked out the Pet Shop Boys as remarkable, both musically and intellectually. They shortly embarked on what Tennant knowingly referred to as their “imperial phase,” in which they had several more British nu ber one singles (including their Elvis cover “Always On My Mind,” which reached number four on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1987, selling over a million copies in the United States alone). Their catchy, witty and somehow oblique songs captured the mood on both sides of the Atlantic, of Reaganite and Thatcherite economic excess where human beings were left behind: witness the heartbreaking lyrics of another single, “Rent,” an examination of a financially dependent relationship in which “I love you, you pay my rent.” Yet the idea that a duo this intellectual and esoteric might endure for another four decades would have seemed comical at the time. To borrow the words of Dr. Johnson on another great eccentric British one-off, “Nothing odd will do. Tristram Shandy did not last.”

Still, here they — and we — are. And although the Pet Shop Boys are no longer the commercial titans they were in their Eighties heyday, they are still a force to be reckoned with, especially live. A double-headline act with New Order across the United States in late 2022, the Unity Tour, demonstrated that they were more than capable of pulling crowds to the country’s arenas, at a time when many of their peers have either disbanded or so far lowered their commercial ambitions as to be playing in midsized theaters, even the small clubs in which they began, seeing their careers go full circle.

There seems little danger that Tennant and Lowe will face such an ignominious decline in their fortunes, even though Tennant has wistfully commented — possibly sincerely — on his belief that the pair will end up playing small outdoor venues in parks without the electronica and lavish stage sets that they have become synonymous with. It is possible to imagine them operating as a modern-day Flanders and Swann, two aged men on piano and vocals delivering witty, satirical and rather sad songs about love, life and loss. But if that time is to come, it is not here yet, and given that Tennant turns seventy this year (Lowe is a comparatively youthful sixty-four) and remains at the peak of his artistic powers, this downturn in fortunes looks unlikely to happen.

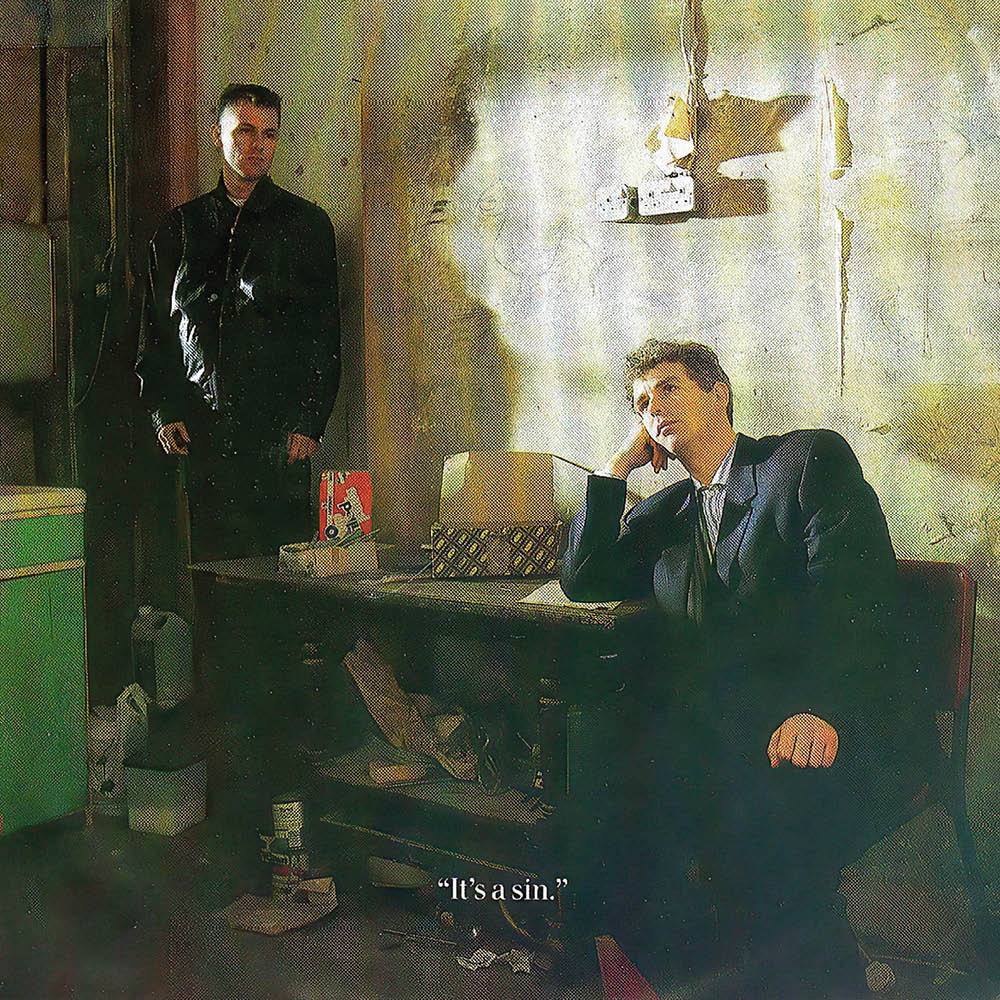

If the appeal in the Pet Shop Boys’ image and music lies in the incongruity between appearance and performance — the way in which two men who could easily pass for successful architects or playwrights are simultaneously celebrating and satirizing the idea of being pop stars at a time when such a phenomenon is traditionally left to the young — then it has helped that they remain such an unknowable pair.

They have a clearly defined image presented to the media in interviews and public appearances. Tennant is hyperliterate, always ready to discuss history or politics or some aspect of popular culture that has somehow affected his writing or thinking. Lowe, meanwhile, who usually conducts his interviews behind a pair of intimidating dark glasses, is monosyllabic to the point of enigma, but usually manages a witty quip or deflating one-liner just when his interlocutor is on the point of wondering why on earth he bothers to participate in such activities.

Neither has ever given any insight into his private life; Tennant came out as gay in the Nineties, and Lowe has never discussed his sexuality publicly. Even their association with politics — a key feature of the first half of their career — has largely come to a close. They were closely associated with Blair’s New Labour government, a period in which they released two albums, Nightlife and Release, that have their moments but rank among their weakest LPs, and then turned on Labour for what they perceived as its authoritarianism, releasing songs that attacked plans to introduce compulsory ID cards (“Integral”) and Blair’s relationship with George W. Bush (“I’m With Stupid”), as well as taking aim at America’s war on terror in “Luna Park.” Since then, however, they have lessened their political engagement, although 2019’s single “Dreamland” obliquely explored Donald Trump and border closures, and the one-off 2023 release “Living In The Past” appeared to equate Putinism with Stalinism (“There’s no defeat that I’ll answer for / The West is effete and they’re begging for more”).

This is all bracingly intellectual stuff, with the tunefulness of the music (traditionally Lowe’s department, although neither has ever commented on the precise division of work) complementing the demanding but never obscure lyrics. The humor and the charm, both quintessentially English qualities, are never far away, however, as you might expect from an act that named itself after a pair of acquaintances who worked in a London pet shop for a time in the early Eighties.

Therefore, their return to the public spotlight with Nonetheless — another of their signature single-word album titles, something that Tennant has suggested is as much a trademark of theirs as an absence of capitalization was for e e cummings — is both overdue, given that it has been four years since their last release, Hotspot, and extremely welcome.

At a time when music, especially pop music, has become the identikit expression of a team of nondescript songwriters working for beautiful young men and women, the eccentricity and idiosyncrasy of Britain’s most commercially successful duo should be cherished and extolled. Welcome back, Boys.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply