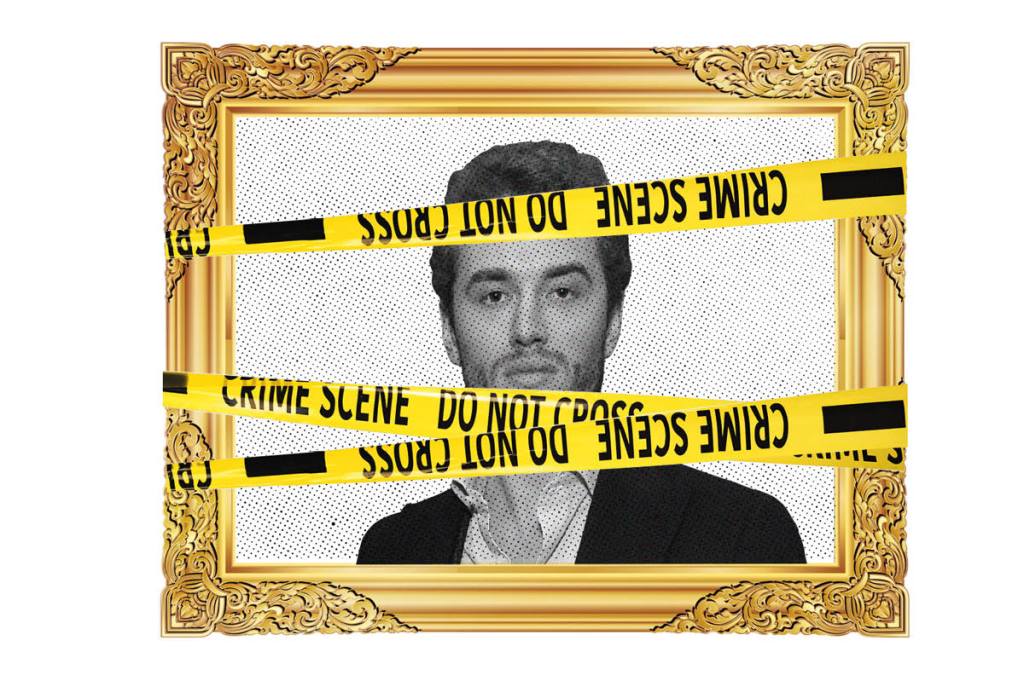

A few months after going on the lam in late 2019, the thirty-two-year-old wunderkind art dealer Inigo Philbrick sent his friend and colleague Orlando Whitfield a trove of documents. Philbrick wanted his old friend to write a sympathetic account of the misdeeds he stood accused of — since described as the biggest art fraud perpetrated in US history, for which Philbrick was later convicted and imprisoned. Whitfield has instead written All That Glitters, a memoir chronicling their friendship and dealings during a heady “gold rush” decade in the art world. Going through Philbrick’s correspondence and the court documents, Whitfield realized his friend was not the person he purported to be, certainly not the one his clients believed he was. Like Jay Gatsby, to whom he is compared in the book, Philbrick seems to be an elegant but inveterate operator — always on the go, or already gone, around whom rumors, at first favorable, percolated.

Gifted at networking, building an air of mystique while still just a student at Goldsmiths, University of London, where he and Whitfield met, Philbrick’s art-world ascent was notably swift. After graduating, he became assistant collection manager for contemporary London gallerist Jay Jopling’s company Modern Collections. Before long, he was running a gallery of secondary market (pre-owned) artworks with Jopling’s backing, later opening his own galleries in Mayfair and Miami and turning over tens of millions of dollars a year. Sometime around 2017, though, his meteoric ascent began to slow, in step with the prices for the artists he specialized in. The so-called wunderkind, it later transpired, was overselling shares in artworks, in one instance selling around 220 percent of a single painting. He was also falsifying documents and selling works that didn’t belong to him. In 2019, following a disastrous auction he had hoped would restore his fortunes, the highwire act came crashing down.

At first, Philbrick’s antics resembled youthful chutzpah. Whitfield details the pair’s early, gonzo-style art deals, from flying a Paula Rego watercolor via Ryanair to Lisbon for a cash sale, to attempting to buy a metal door with a Banksy rat on it. There’s a drip-feed of increasingly dodgy dealings, but the warning signs are there from the start, not least flagged by Philbrick’s tendency to keep his friends and associates in the dark. Happily for him, the art world’s “discretion” provided him with both opportunity and cover.

Whitfield, who worked with and for Philbrick for a time, believes his former friend was an avatar of an underregulated system and a turbocharged art market which allowed a spectrum of questionable, not-quite-illegal practices to flourish. Unscrupulous actors can, as Philbrick’s case shows, take advan- tage of the fact that, for example, multiple investors are able to buy shares in artworks without ever having seen them. The complexity of the art market’s rules makes it difficult for outsiders to fully grasp its workings and what is and isn’t permitted. In her excellent deep dive into the art world, Get the Picture, Bianca Bosker quotes a gallerist who remarks, “We’re all white-collar criminals.” Even the storied auction houses Sotheby’s and Christie’s operated a price-fixing cartel for much of the 1990s — it ended in huge fines, a class-action lawsuit and the conviction of the chairman of Sotheby’s. Whitfield is scathing about the art market’s “speculectors” who buy art purely to inflate prices and boost profits, and it’s possible Philbrick was able to deceive himself that he was acting within a gray zone. Yet Whitfield can’t let him off the hook and neither did the US District Court judge who in 2022 sentenced Philbrick to seven years in prison (he was released earlier this year).

Though neither as idiosyncratically compelling as scam artist Anna Sorokin, nor as blankly fascinating as Theranos’s Elizabeth Holmes, the Philbrick in All That Glitters comes across as rampantly ambitious, addicted to sniffing out deals. (In a 2020 piece for New York magazine, Kenny Schachter, another of Philbrick’s one-time friends as well as one of his victims, paints him as less a Gatsbyesque cipher than a gifted upstart with a taste for drugs, prostitutes and private jets.) In the end, he is also a symptom of a culture obsessed with the too-good-to-be-true and an ecosystem happy to follow the money. When a forged artwork suddenly appears, the credulousness of people who ought to know better may be explained in part by the desire to believe a good story as much as by the desire to profit from it. Precocious and ambitious, in possession of some dazzle but also the right credentials (his father a museum director, his mother an artist), Philbrick had a keen understanding of the art world’s arcana from the very beginning. He was never a neophyte, much as he has suggested that he was in over his head. The art world — the art business — is a society underpinned by gatekeeping, with its own set of unwritten and seemingly immutable codes. This latest tale of art-market legerdemain makes clear that sociocultural gatekeeping proves no substitute for meaningful checks and balances.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply