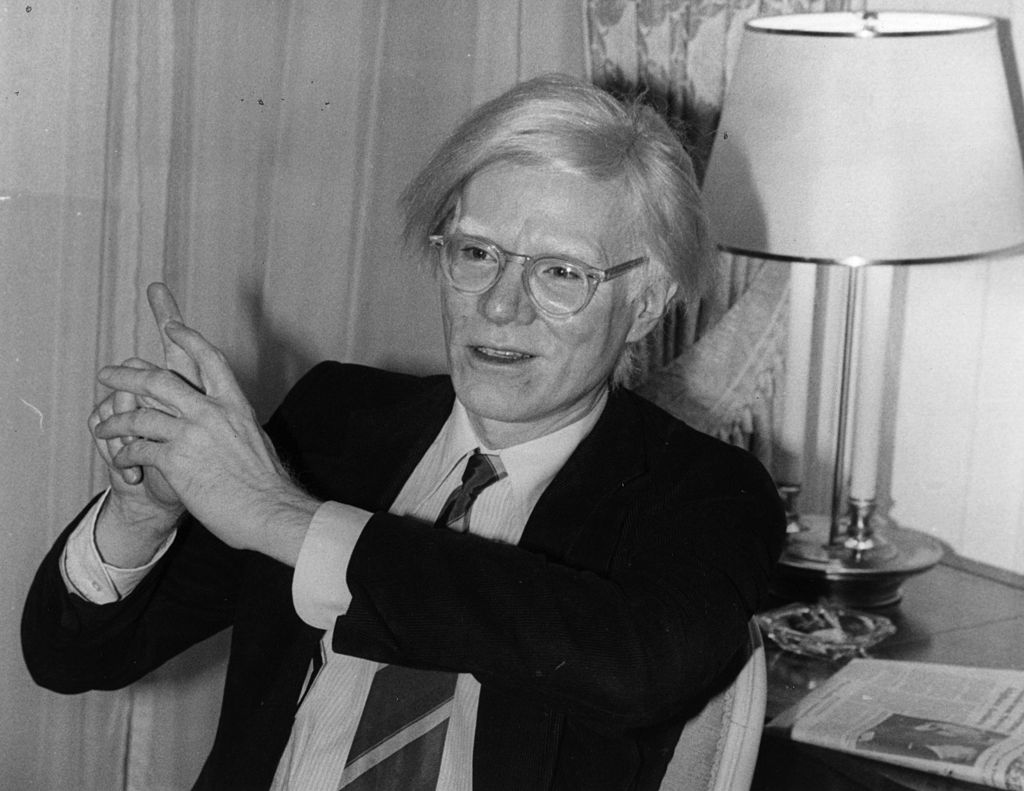

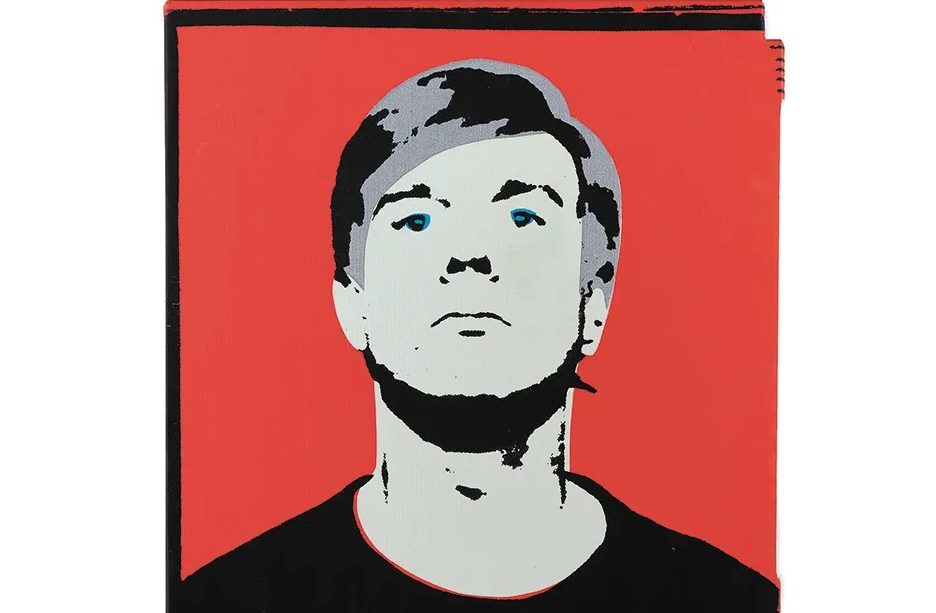

A lawsuit on the work of Andy Warhol is going to the Supreme Court. In 1984, Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to alter a photograph Lynn Goldsmith took of Prince in 1981 for Newsweek. Warhol cropped the original photo, overlaid it with purple and orange, outlined parts of Prince’s face, and added shading to accompany an article by Tristan Fox titled “Purple Fame.”

Goldsmith apparently only learned in 2016 that Warhol had altered her photograph when Vanity Fair republished Warhol’s work in a story on Prince’s death along with the other 15 pieces Warhol created from the photo for his private collection called “Prince Series.” She was planning to sue the Warhol Foundation for copyright infringement when the Foundation asked a federal court in Manhattan to rule that the Warhol paintings were protected by fair use. Goldsmith countersued in 2017. The judge ruled in favor of the Warhol Foundation in 2019, but the Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Goldsmith in 2021, stating that “the works in question do not qualify as fair use as a matter of law” because they are “substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photograph as a matter of law.”

In his majority opinion, Judge Gerard E. Lynch argued that Warhol’s paintings were not significantly “transformative” to qualify for “fair use.” He wrote that “the bare assertion of a ‘higher or different artistic use,’ is insufficient to render a work transformative”:

Rather, the secondary work itself must reasonably be perceived as embodying an entirely distinct artistic purpose, one that conveys a “new meaning or message” entirely separate from its source material. While we cannot, nor do we attempt to, catalog all of the ways in which an artist may achieve that end, we note that the works that have done so thus far have themselves been distinct works of art that draw from numerous sources, rather than works that simply alter or recast a single work with a new aesthetic.

Unlike Jeff Koons’s Niagara and Richard Prince’s “Canal Zone” series, the Court argued, “Warhol’s modifications, serve chiefly to magnify some elements of that material and minimize others. While the cumulative effect of those alterations may change the Goldsmith Photograph in ways that give a different impression of its subject, the Goldsmith Photograph remains the recognizable foundation upon which the Prince Series is built.”

If Warhol’s “Prince Series” (which was clearly created for commercial use) were declared to be protected by fair use, Judge Lynch continued, it would significantly affect not only the market for Goldsmith’s photograph but other such photographs as well, since “permitting this use would effectively destroy that broader market, as, if artists ‘could use such images for free, there would be little or no reason to pay for [them]’ . . . This, in turn, risks disincentivizing artists from producing new work by decreasing its value – the precise evil against which copyright law is designed to guard.”

Would it? I wonder. In The New Republic, Matt Ford notes that many of Warhol’s “most well-known compositions came from the work of photographers, designers, and artists who did not become household names like him.” But would they have if Warhol hadn’t used their work? How much more would Goldsmith have earned for her Prince photograph if Warhol hadn’t used it? What financial harm was done?

That will be the question the Supreme Court will consider at length as much as the question of whether Warhol’s work is sufficiently original.

Ford writes that in an amicus brief, a group of art law professors argued that if the Supreme Court upheld the Second Circuit’s decision, it would “strip protection from thousands of storied works of art and…chill expressive activity and artistic creation.” That’s unlikely. The Second Circuit made a relatively clear distinction between Warhol’s use of source material and that of both Koons and Richard Prince’s. But it may strike a blow to conceptual art, which is hardly art at all.

The Supreme Court will hear the case in the fall.