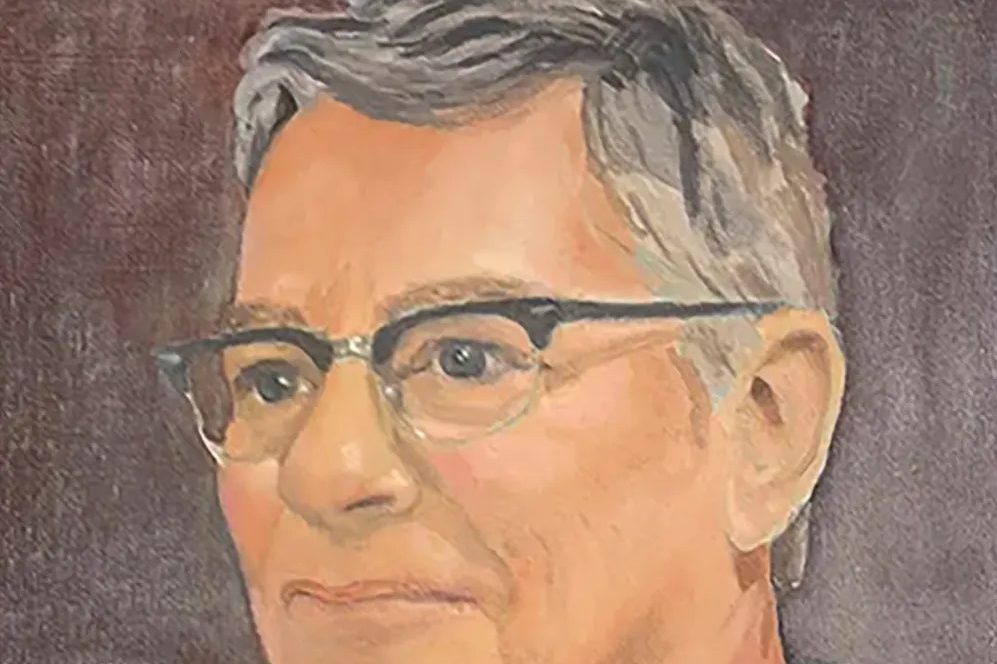

Jack Karlson, who died this week aged eighty-one, was an Australian small-time crook, prison escaper and colorful character who had a tough and difficult life. He was also, however, the reluctant star of a 1991 TV news report that later became an internet sensation.

Back then, Karlson was having a bite to eat in a local Chinese café in suburban Brisbane, when, like Monty Python’s Spanish Inquisition, a posse of Queensland police suddenly and unexpectedly swooped to arrest him. Thanks to a tip-off to a journalist, it was all captured on camera.

According to the news report, Karlson was being followed by “an American Express investigator” who had identified him as a suspected credit card fraudster. The investigator called in the police, who came in numbers to apprehend Karlson and inadvertently gave him internet immortality.

To say that Karlson did not come quietly is an understatement. His bundling into a police car by half a dozen burly constables, and an off-duty detective, has become the stuff of legend. That Karlson himself had a deep, stentorian and highly theatrical voice booming from his rumpled, larger-than-life, Falstaffian figure added to the spectacle. Imagine a stubbled Brian Blessed in a half-buttoned polyester shirt, caught in the middle of a police scrum.

Looking over the roof of the car at the TV camera, policemen struggling to contain, let alone restrain him, Karlson gave the performance of his life. “What is the charge? Eating a meal? A succulent Chinese meal? Gentlemen, this is democracy manifest!” he boomed with a rolled-r flourish that can’t be replicated in print: it simply has to be watched.

Then Karlson pointed at one of the cops: “See that chap over there?” he bellowed, before demanding (he later admitted without foundation) that the policeman, “get your hand off my penis!” It was only then that Karlson was finally subdued and taken away to the local “cop shop.”

What of the “succulent Chinese meal?” In the news report, an interviewing detective remarked on Karlson having a flair for amateur theatricals and labeled him “a prolific false pretender.” In labeling his Chinese meal as “succulent,” Karlson certainly was pretending with a heavy dollop of irony — Australian suburban Chinese cafés are legendary for their cheap but bland and tasteless food, often with the consistency of soggy cardboard.

Karlson was bailed — although years later he suggested that he actually skipped bail and absconded yet again from custody — and to the end of his life insisted that the whole thing was a matter of mistaken identity.

Whether it was or not, the man born Cecil George Edwards was never charged. He died this week having dined off his 1991 dining misadventure ever since his first online notoriety almost twenty years ago. Indeed, in the past month Karlson, and one of his arresting officers — with whom, in the tradition of Australia’s original convict settlement, Karlson had become great friends — had been doing the Australian media rounds to promote a new documentary about the incident and Karlson’s hardscrabble life.

Some of those presenters patronizingly treated Karlson and the episode as a huge joke. But that attitude misses a key point about why the incident still resonates with many. The heavy-handed and over-the-top police restraint of Karlson, and that his arrest turned out to be unjustified, strikes a chord with viewers of the online clip. This is particularly the case for those who felt the forceful hand of authority on their own shoulders in Australia’s excessively repressive Covid years, and consider their lives blighted by the two years when the country became a byword for lockdowns, curfews, and ordinary Australians being denounced, and even humiliatingly arrested, if they resisted.

Many in Australia, and no doubt others around the world, relate Karlson’s televised moment of infamy to their own harsh experiences of governments’ authoritarian Covid responses: for a time, we were all Jack Karlson. This put-upon Aussie battler was transformed by this one experience into an Everyman, and that is the key to his immortality as an online folk hero.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply