As preface to his verse play King Victor and King Charles (1842), Robert Browning made a striking assertion about the claims poetry has on truth. In dramatizing King Victor Amadeus II of Sardinia’s abdication and subsequent attempt at re-accession, Browning said, he had produced a “statement” on the subject “more true to person and thing than any it has hitherto been my fortune to meet with.”

Naturally, that “statement” — peculiar word for poetry — differs considerably from the historical record. Yet the merits Browning ascribes to his version — not surpassing beauty, but truth to “person” and “thing” — we would tend to call prosaic, the province of history or science or some other species of nonfiction. A critical theorist might tell us that the poet has confused his genres here, that an audience can’t and won’t expect historical truth from an embellished account. Socrates would have kicked him out of the polis.

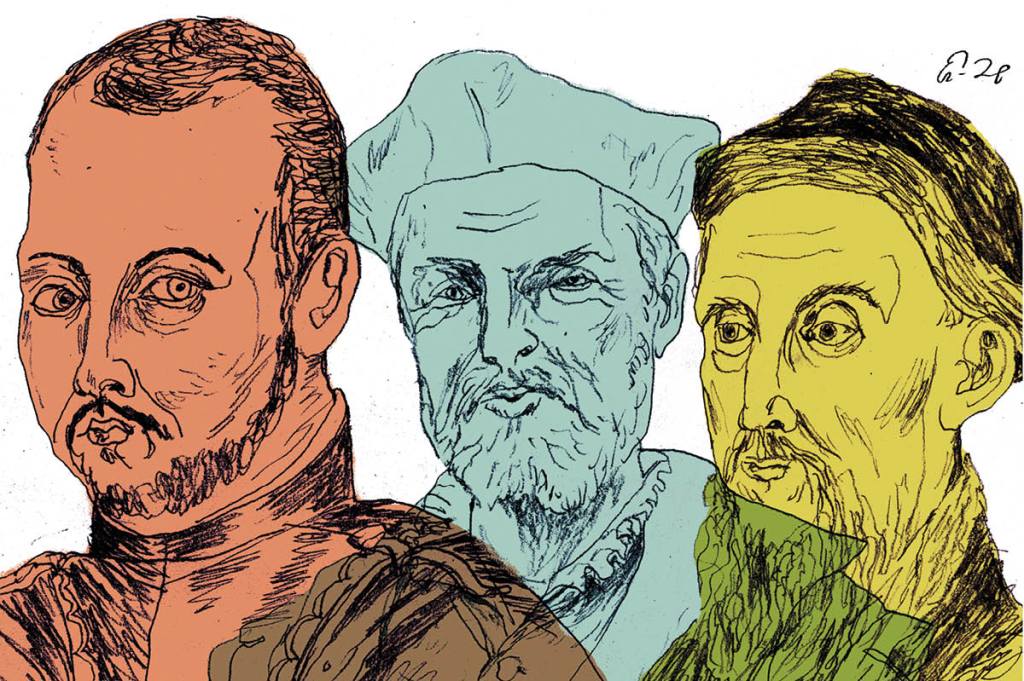

To my knowledge, Jane Clark Scharl has made no such truth claims on behalf of her new verse play Sonnez Les Matines, a tidy and clearly fictitious account of an evening passed by John Calvin (here Jean Cauvin), Ignatius of Loyola and François Rabelais in 1520s Paris — Shrove Tuesday, the last night of Carnival festivities, the day before Lent. (The three men were indeed there at the same time, Cauvin and Loyola both students at the University of Paris; the rest is speculation.) But in its sly, unassuming way, the drama makes a case not too different from Browning’s: for poetry as a boundary-crossing genre, capable of synthesizing fact and feeling, philosophy and persona, and arriving at truth.

Sonnez owes a good deal to Browning, as it happens, not just as a verse play (as all serious dramas were in his day) but in its psychological acuity and its dramatic expression of the mutability of human will. During the Shrovetide revels, the three protagonists stumble over a slain body in a back alley, not all of them unwittingly. At different points in the evening, each of the three is suspected of the murder. The whodunit plot, however, is less a source of the drama than a platform for it. The real interest lies in how each character acts under suspicion: apparent shock, wily denials, hints of guilt, tergiversations, grudging concessions and abject grief, in every which order and all over again.

Animating these vacillations are the moral sentiments of the historical personae. Cauvin and Loyola tend to express themselves in spiritual terms befitting their respective theologies. Cauvin, who denied the physical presence of Christ in the Eucharist, puzzles over that Protestant sticking point when things get messy, “wonder[ing] just / what is meant by the body, / and what signifies the blood.” Loyola — soldier, nobleman and author of the Spiritual Exercises — shows good humor and restraint in all matters, save when his honor is called into doubt. As poetic figures, both hearken to the tempted Thomas à Becket in T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral: Cauvin for gloomy, fatalistic musings, and Loyola for courting spiritual pride.

But Murder in the Cathedral unfolds at a stately, classical pace; Sonnez Les Matines zags and caroms, whipping among the three interlocutors. Probing guilt from all angles, the exchanges carry a whiff of Dostoevskian psychodrama. Vladimir Nabokov once quipped that Dostoevsky had been destined “to become Russia’s greatest playwright, but he took the wrong turning and wrote novels.” Scharl’s presentation has the advantage of being more digestible than Crime and Punishment.

Rabelais serves as counterbalance to the two heady theologians. In crafting his character, Scharl has well heeded the doctor and humanist’s injunction in the proem to Gargantua and Pantagruel: “Mieux est de ris que de larmes escrirpre / Pour ce que rire est le propre de l’homme” — roughly, “Better to write for laughter than sorrow, / Because laughter belongs to man alone.” Sonnez’s wi tiest and raunchiest lines belong to Rabelais, and they come thick and fast. The challenge, then, for the playwright — who has clearly delighted in the composition — is to keep this force of nature in sync with the play’s overtly theological themes.

In the preface to Sonnez Les Matines, Scharl acknowledges the fundamental difficulty of her subject matter. “We human beings,” she writes, “are a bit like bridges… We are something entirely new: a physical spirit, an embodied soul. And to complicate matters, it is through our bodies that we both sin and are saved.” That the play is set during “the frail hours that bridge Carnival and Lent” underscores this dilemma: in a liturgical sense, Rabelais, Cauvin and Loyola must all pass from that raucous, freewheeling celebration of the body to the quiet season of self-denial and reflection. To acknowledge the bridge from body to spirit is one thing, to express it in language quite another. How can words approximate the state of a soul, much less an embodied one?

A clue might be found in the Christian sacrament of confession, which plays a key role in the passage from Carnival to Lent (the sins accrued during the former must be cleansed in preparation for the latter). Nowadays, “confession” is popularly construed in a dry, legalistic sense: wrongdoers ought to own up to crimes of which they’re accused, we reckon, and even those of which they’re not — because it’s the right thing to do.

The Christian tradition, however, construes the notion more dramatically. The commandments of God are inscribed not only in the Bible but on each individual conscience; in the confessional, a man must accuse himself and prosecute the charges himself. To an eavesdropper — as for the audience of a verse play, if we accept John Stuart Mill’s assertion that all poetry is “overheard” — such an arrangement is as tantalizing as it is recondite. For even if we knew what was said in the confessional, we could nowise know that it accurately reflects the state of the soul.

In literature, Augustine’s Confessions remains the model for this genre of self-reckoning. At various points Augustine refers to his account as praise, sacrifice, thanksgiving and prayer, as well as a model that readers may know “the depths from which we call out to God.” Sonnez arrives at no confession in the legal sense, at least for the murder. But in the Augustinian sense, the whole play operates as a wide-ranging, triplicate confession. Taken individually, each character is his own fusion of habit and mind, body and soul. Taken dramatically, in their mutual proddings and recriminations, the trio articulate the moral vexation that follows on guilt and the dogged hope that awaits salvation.

I have tried to demonstrate a few of the ways in which Sonnez Les Matines ventures into nonfiction— history, theology, psychology — as well as the creative means by which it correlates those elements. But perhaps this is backwards. Eliot once wrote that, if a work of literature “does not excite us before we have understood it, no commentary will reveal to us its secret.” Poetry excites by the mouth and ear, and drama further by the eye. What, then, might be said of this verse play in performance?

Sonnez is, alas, unlikely to attract a large following in the theater: the subject matter is too niche, and probably pitched over the heads of most audiences. But the play stands perfectly well on its own, as poetry and without a stage. It would fit neatly into that category of drama known as “closet plays,” intended to be read in a group setting rather than acted out: the dialogue is stimulating enough, the action straightforward enough, the characters finely drawn.

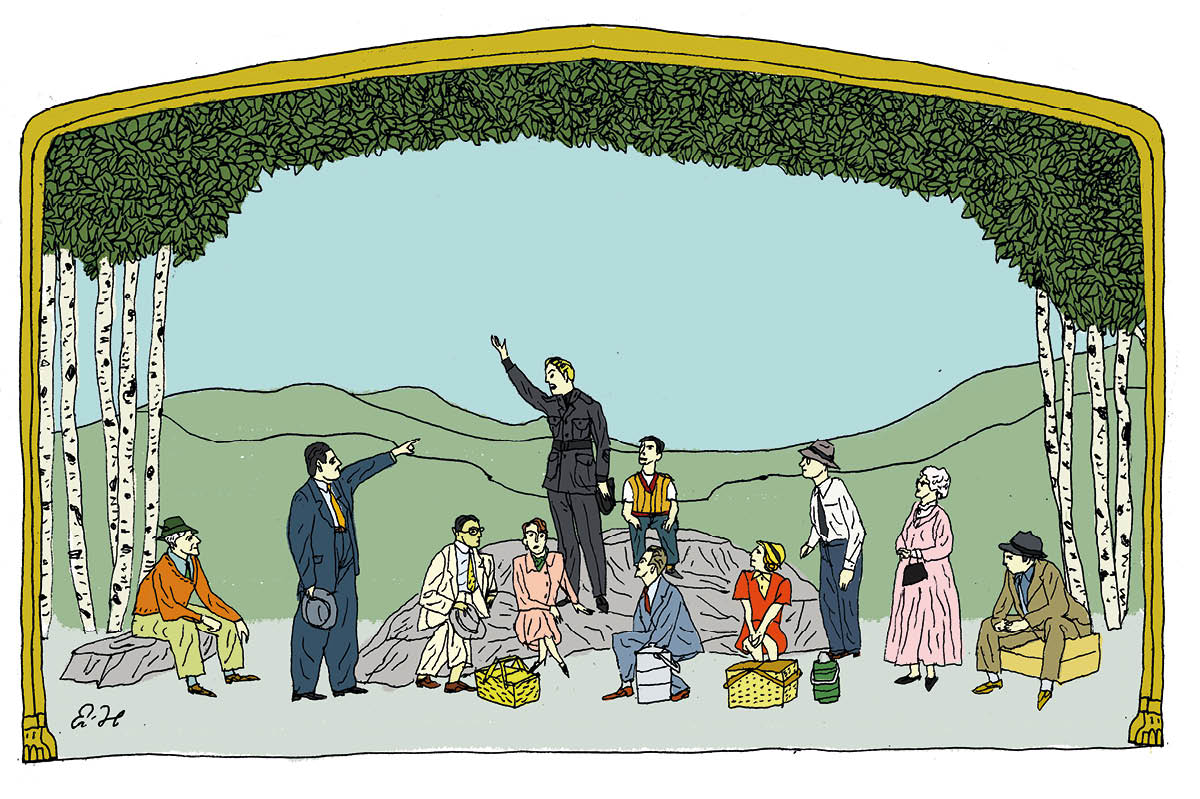

The merits of a proper production, however, are undeniable. I had the good fortune to see Sonnez in a small, off-off-Broadway staging this spring, directed by Conor Kopko and featuring Micah Price as Rabelais, Hari Bhaskar as Cauvin and Max Conaway as Loyola. (Bhaskar and Conaway were capable, but Price stole the show as Rabelais.) What impressed me most about the production was, curiously, the versification. Rabelais, Cauvin and Loyola each favor a distinguishing meter: rhyming couplets, blank verse, and iambic tetrameter, respectively. These must be spoken aloud to glean their effect, so perhaps it was the advantage of trained actors over my solitary readings that heightened my interest; perhaps, the fact that we tend to expect verse in printed works but not on the stage.

Whatever the case, the result was marvelous. From half-truths and art, Scharl has given us artful truth. To borrow from Augustine, Sonnez Les Matines is a play in which “things fit not only within their places but also within their time.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2023 World edition.