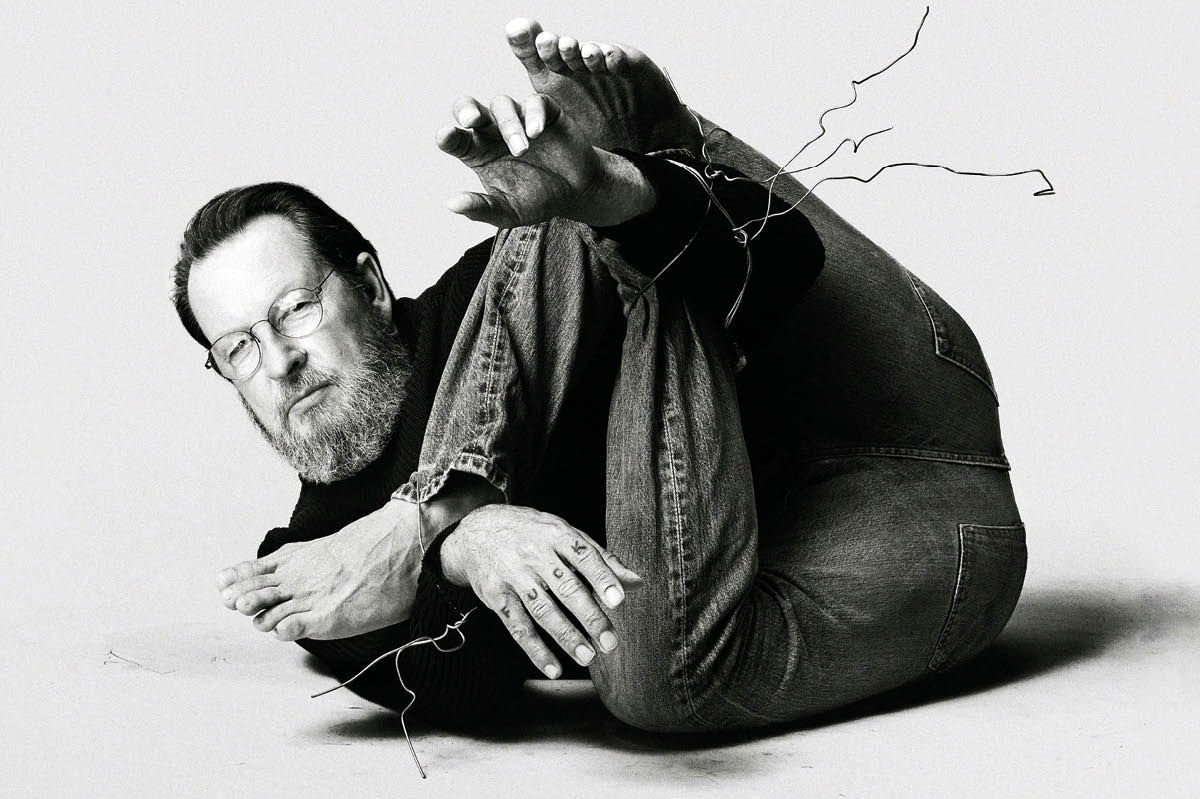

The telephone was ringing. On the other end was Markus Hinterhäuser, artistic director of the Salzburg Festival. “Robert, would you like to direct a new production of Jedermann for us next year?”

A new Jedermann at the Salzburg Festival, but with only a few months to prepare? I hesitated for about one second before saying I would be delighted and honored to direct.

Jedermann is the complex, frightening, inspiring and fascinating German adaptation by the great Austrian writer and poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal of the English medieval morality play Everyman. Hofmannsthal’s adaptation premiered at Berlin’s Circus Schumann theater in December 1911. Some years later, Max Reinhardt, the play’s original director, suggested that it be staged again as the opening performance for the first Salzburg Festival, which Reinhardt, Hofmannsthal and Richard Strauss were in the process of creating. The idea was to stage the play outdoors, in front of the magnificent Salzburg cathedral. It was an enormous success, and has been performed almost every year since, with the most talented Austrian and German actors and actresses in the principal roles. In fact, since the Salzburg premiere, the play has only been directed once before by a non-Austrian- or German-born director, so this was indeed a very special invitation.

God, as the curtain rises, is unhappy with man in general, and Jedermann in particular, as neither seems any longer to believe in Him or to live their lives guided in any way by a sense of the Divine. So God sends Death to Jedermann, who is in the prime of his life, to tell him that his time on Earth is over and that he must make an accounting of his life. Before Death’s untimely visit, we see Jedermann in his daily life, refusing to be charitable to the poor, or helpful to a ruined business partner, or respectful to his elderly mother; he is much more occupied with making money and preparing an enormous party for his latest girlfriend. When Death suddenly appears at the party, Jedermann’s fair-weather friends and relations immediately desert him. He realizes that he will have to journey to meet his maker on his own. In so doing, he discovers the value of Good Deeds and Faith he has always chosen to ignore and meets his death repentant and redeemed — in spite of the Devil’s last-minute attempt to snatch him away from God.

In adapting Jedermann, Hofmannsthal gave it an important subtitle, The play about the death of a rich man. This was not simply because a rich man would have more to lose: in 1911 Hofmannsthal was preoccupied with the growth of capitalism, which he saw increasingly developing as a destructive force. Writing about Jedermann, Hofmannsthal observed, “We are in the darkness and in sore straits; in a different way from that of medieval man but to no less a degree. We survey and penetrate many things and yet our actual spiritual power of sight is weak. We have power over many things, but we are not rulers. What we ought to possess possesses us, and what has become the remedy above all remedies — money — is now, by devilish perversity, a goal to be set above all others.” It seems to me that the problems that worried Hofmannsthal have become even more acute 113 years later.

This play deals above all with the one great mystery we all have to face: death. As human beings, it is not in our nature to accept the fact of our own deaths. For most of us, death seems to be something that happens to other people. And when death does come, as come it must, it will always be too soon. But why is that so? When we cling to our lives, what exactly are we holding on to so desperately? Jedermann explores all that, and more. Its power and resonance come from the fact that, however codified the telling of the story may be, its subject matter concerns every single audience member, every performance, every year. There are not many plays for which the same can be said.

In his Jedermann, Hofmannsthal deals with the fundamental question of death, and the question of how — if at all — we can equip ourselves for it. Religious preparation for men and women of any faith can be essential, but I think Hofmannsthal also greatly valued the relationship that art has to death. He developed the theme time and again in his work, broadening the way death defines our lives to include a constant questioning of the concept of time. Investigating time became art in Hofmannsthal’s hands, and, in a way, Jedermann’s place in the Salzburg Festival over so long a period seems to have become a confirmation of the importance that all art, all the arts, can have in our lives. Art, which has been shown time and again to be the only thing that remains when civilizations fall, can help us deal with — perhaps even cope with — the transitory nature of life and the finality of death. This is perhaps one of the reasons why Jedermann has become almost symbolic of the Salzburg Festival.

Hofmannsthal, I believe, was not only writing the play as a warning; he also wanted to celebrate the idea that there is something beyond human life. However, we know from his 1912 essay Das alte Spiel vom Jedermann that he did not mean this play to work only for people who believe in the tenets of Christianity. His aim was more universal. My instinct is that Jedermann is more about how to live than how to die. Jedermann’s motto is carpe diem. But if you only live like that, don’t you risk doing so at the expense of other people — even if you are the one footing the bill?

Max Reinhardt’s idea that the play should be performed in front of Salzburg Cathedral, in the heart of the city, is full of resonance, and full of joy. The cathedral is an astonishingly powerful building. The proximity of the stage to the 2,500 members of the audience means that there remains an intimacy, in spite of the vast scale. With my co-set designer, Luis F. Carvalho, we decided to use the cathedral itself as our set, rather than build another one in front of it, and to use the building itself to match the scale of the temporal and spiritual power Hofmannsthal explores in the play.

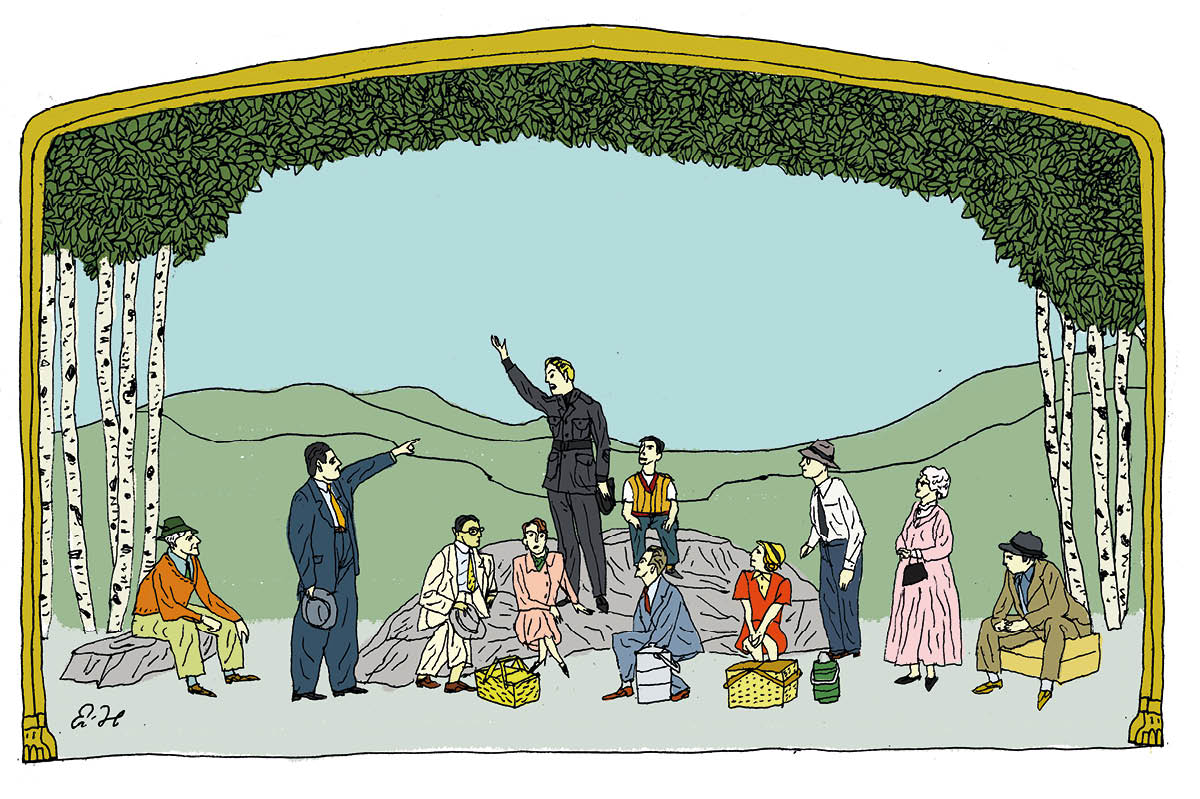

In Jedermann, one of the director’s many challenges is to find the balance between the characters, some of whom are real and some of whom are allegorical. They can be presented in many different ways, depending on what theatrical style is selected. In the end we chose an almost cinematic realism to help us understand Jedermann and his fantastic wealth. We’re going to attempt to change in front of the audience’s eyes the vast facade of the cathedral, the house of God where the play begins, into Jedermann’s palace, the house of a man. We’re even going to try to change the point of view later on, so that at first we’re in front of the house (where Jedermann first arrives fresh from a round of golf, in his gilded, chauffeur-driven car), to the garden at the back of the house, where he eventually throws his fabulous party, complete with ten-piece band. In a nod to the medieval Dance of Death, which was one of Hofmannsthal’s inspirations for his adaptation, we have introduced a lot of music and dancing.

There are many more design and directorial questions, such as how to present the allegories of God, Death, Mammon, Good Deeds and Faith. Challenging but also extremely fulfilling choices need to be made, and fortunately we have a terrific cast of more than twenty performers and sixty extras to bring this material to life.

We hope not to lose sight of the fact that although the play concerns the sacred, it is not sacred in itself. In fact, the whole play is a celebration of life through an acceptance of death. It is at once a memento mori and a vanitas, a christening and a funeral rolled into one. It is a précis, a metaphor and an allegory of life, and although life is not a rehearsal, everyone (jeder Mann) involved realizes what a gift it is to be able to rehearse and perform this play.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply