Sandra Newman’s Julia has a connoisseur’s nose for body odor. When she gets close to another person or animal, she almost always notices their smell — manly, dusty, dungy, a hint of talcum powder. When she suppresses emotion, she sweats. She sprains her wrist and tears rise “of themselves like sweat.” In a pivotal scene, she unblocks a gruesomely overflowing toilet. This abundance of bodily functions feels like a reminder of George Orwell’s original Julia in Nineteen Eighty-Four, whose physical abandon makes her an object of desire and symbol of rebellion.

This fantasy is punctured in Julia. Bodies are sensuous but they are also skin-crawlingly horrible. Mutilated wrecks, with teeth and nails removed in the Ministry of Love, creep around London on all fours. Suffering and sensuality become two sides of the same problem when Julia is confronted with flesh-eating rats: “They wanted a meal. But that was all they wanted.” Not malevolence, just bodies being bodies: “These were animals,” she says, and might be talking about the humans too.

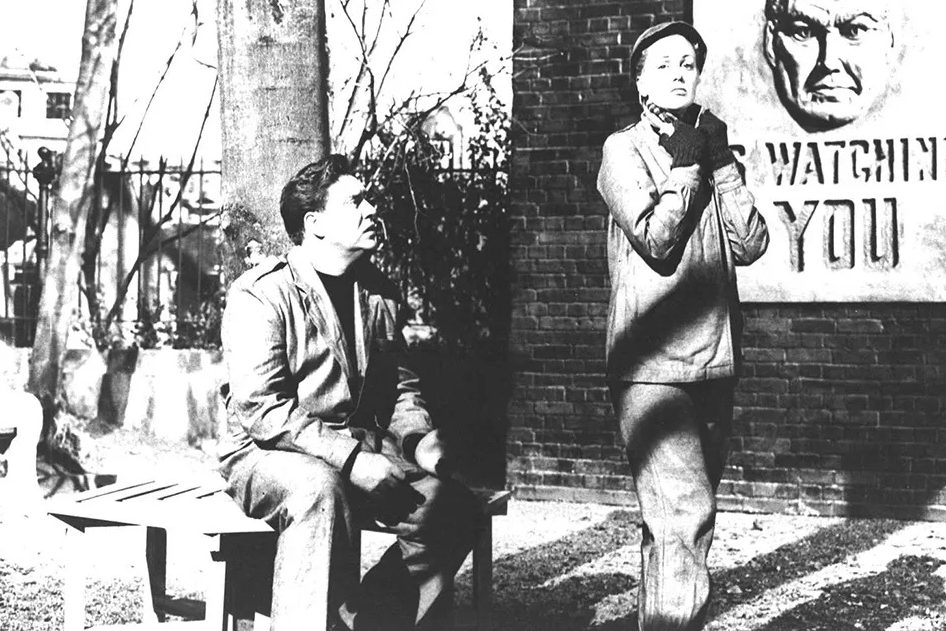

Unexpectedly for a novel riffing on Orwell’s political dystopia, it seems like it wants to be the opposite of political. The way bodies are handled — their need for comfort, their impulse for survival — doesn’t leave room for much else. Beliefs and relationships dissolve into delusion or “sham.” If Orwell’s novel is a fable of ideology gone wrong, Julia is the story of a young woman who believes in nothing. The book dispels many of Nineteen Eighty-Four’s ambiguities (the curtain draws back and reveals Big Brother, a senile old man who has soiled himself) and lacks its conviction. Sometimes this allows for subtler shading but often it just feels apathetic and directionless.

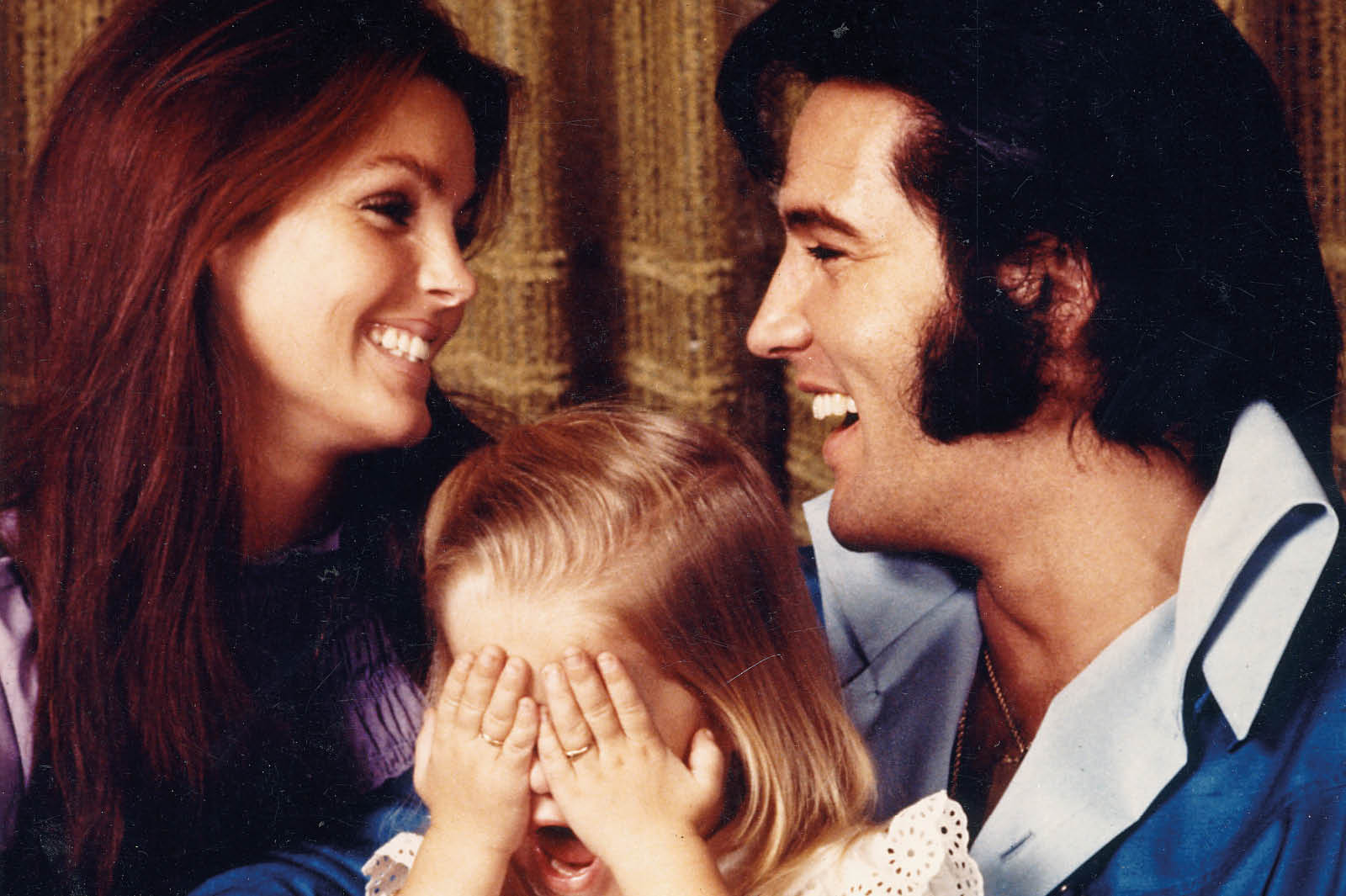

After her time in the Ministry of Love, Julia begins reading novels produced by machines, with titles such as War Nurse. Her life quickly takes on the flavor of these books. She bounces along in a jeep with soldiers who quote Wordsworth and remind her of the airmen she idolized as a child. It feels like the false ending of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil but without the punchline revealing it as escapist fantasy. Of her own complicity in murder, Julia reflects: “One had no choice. One tried to be kind whenever one could. One survived and then one was sorry.” By the end, Julia only longs to put roses in her hair and take a bubble bath in a golden tub.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.