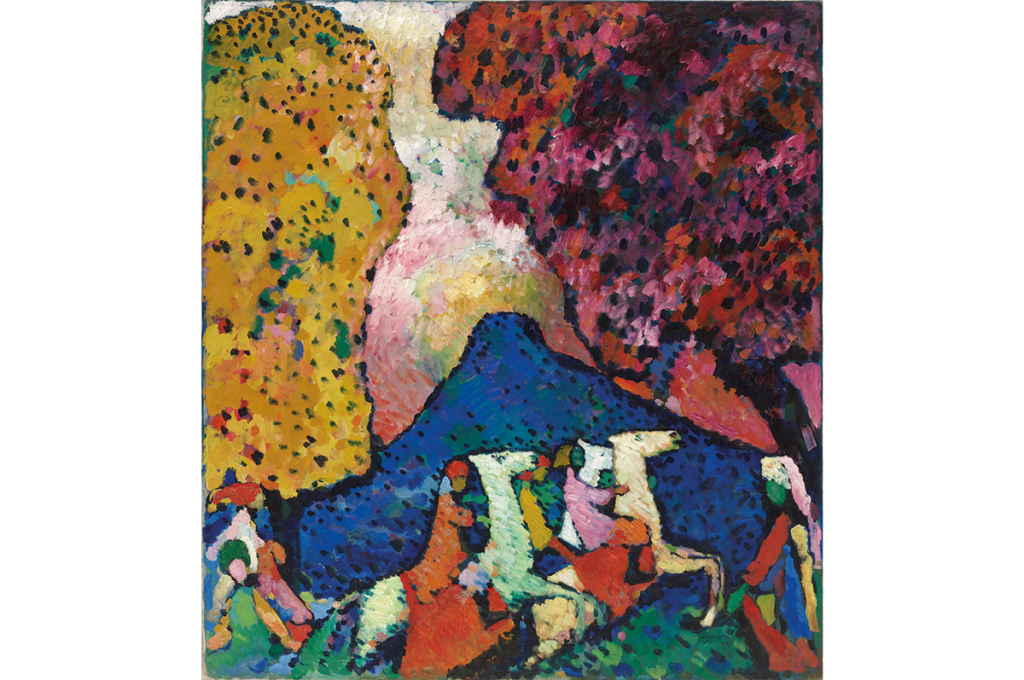

The paintings of Vasily Kandinsky (1866-1944) have never looked quite as good as they do, right now, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. It’s worth mulling why that is. I mean, Kandinsky is old news, right? He’s a mainstay in the common consciousness of those who make art their livelihood, and the paintings remain on view at any institution that presumes to untangle the story of Modern art. Given the current vogue for politics and inclusivity, Kandinsky seems an unlikely figure for reappraisal: he’s a tough nut to enlist for this or that cause. As for excluding him from the canon — forget it. Dead white male though he may be, Kandinsky is immovable. Granted, his status as the first abstract painter has been called into question. A few years back, the Guggenheim mounted a survey of canvases by Hilma af Klint, the Swedish visionary who, we were told, painted the first abstraction in 1906 — beating Kandinsky to the punch by a good decade. An interesting factoid, for sure, but making a horse race of history rarely tells us much about the quality of the work under consideration.

Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle was organized by Megan Fontanella, the Guggenheim’s Curator of Modern Art. As a peg on which to hang an exhibition, the circle is a no-brainer. Geometry is prominent throughout Kandinsky’s oeuvre, particularly in the later work wherein the principles of Constructivism and the Bauhaus figure prominently. (Kandinsky taught at the Weimar branch of the Bauhaus for over a decade.) Wise to the allegorical connotations of the circle — suns, moons, planets, the like— Kandinsky employed them as adjuncts of his mystical leanings.

Like many early abstractionists, he was prone to abstruse belief systems, and counted himself a devotee of Theosophy, a species of cross-cultural spirituality founded by the redoubtable Madame Blavatsky. “Several Circles” (1926), a canvas in which an abundance of circles float within milky patches of black, could well serve as a stoner’s riff on the Big Bang. “Several Circles” is a staple of the museum’s collection and, in fact, all the items on display — not only paintings, but also watercolors, woodblock prints and illustrated books — are culled from the Guggenheim’s holdings.

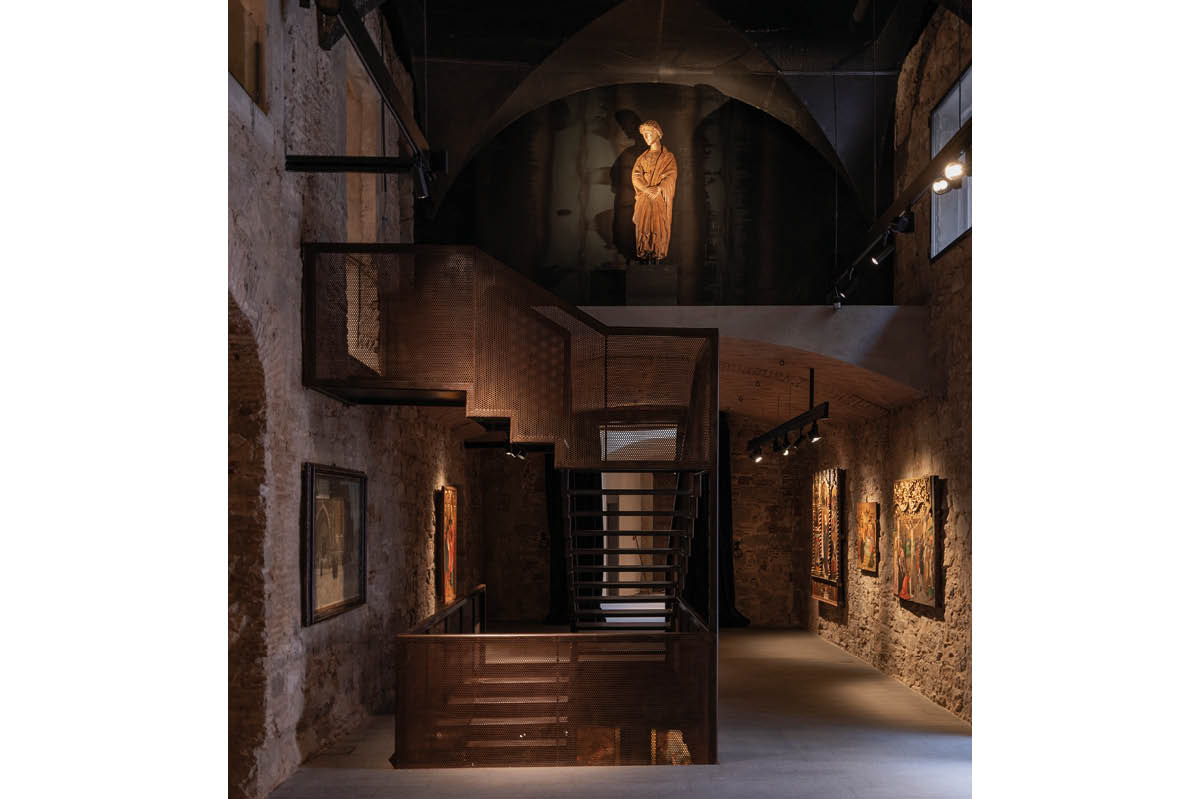

Fontanella circles Kandinsky in another way: Around the Circle is, in significant part, an iteration of the museum’s original mission plan. Ambling among Kandinsky’s kaleidoscopic accumulations of glyphs, squiggles and biomorphs, one is reminded that this tourist-laden fixture of Manhattan’s Upper East Side was once something more marginal and considerably less tony. Founded in 1937, the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (as it was then known) was the doing of two people: Solomon R. Guggenheim, a businessman who had made a fortune in textiles and mining, and Hilla Rebay, his advisor and muse.

Rebay, a full-time connoisseur and sometime painter, left her native Germany with a purpose: to proselytize on behalf of advanced art. Kandinsky was her poster boy. Rebay had Guggenheim by the ear; Guggenheim took Rebay at her word. The industrialist purchased 150 Kandinskys, making his museum the world’s single largest repository of art by the Russian abstractionist. Frank Lloyd Wright’s building, with its vertiginous warp and woof, provides a happy environment not only for Kandinsky’s quixotic ambitions, but those of Guggenheim and Rebay as well.

Fontanella uses the museum’s distinctive architecture in a similarly quixotic way. Ascending the Guggenheim’s ramp — beginning at the beginning, as it were — we notice that Kandinsky’s art is set out in reverse order. Museumgoers start at the end of the artist’s working life and are led up to his early experiments in Post-Impressionist facture and Symbolist form. The installation, we are informed, “reconsiders Kandinsky’s career . . . as a circular passage through persistent themes centered around the pursuit of one dominant ideal: the impulse for spiritual expression.”

How does this bassackwards approach succeed in its goal? Pretty well, I guess. Kandinsky, Fontanella insists, was ever thus. But the same could be said for any artist of note. The commonalities in “Ribbon With Squares” (1944), a bopping inventory of cartoonish shapes, and the sloping forms and encompassing spatial sweep of “The Golden Sail” (1903) aren’t made any more evident by upending chronology. It’s enough to make you think that some curators are getting a mite bored with their duties.

Vasily Kandinsky was born in Moscow to a family of means: his father was a tea merchant, his mother a scion of the upper class. After studying law, economics and statistics at the University of Moscow, Kandinsky did fieldwork amongst the Zyrians, a tribe located in northwestern Russia. That experience proved transformative. Upon entering the homes of the local population — architecture rich in color and decorative ornament — he “felt surrounded on all sides by painting.” It wasn’t until Kandinsky reached the age of thirty that lightning — or, rather, Claude Monet and Richard Wagner — struck. Upon encountering the former’s haystack paintings and the latter’s Lohengrin, Kandinsky felt the pull of art — it resounded, he wrote, like a “wild tuba.”

No time was wasted: Kandinsky packed his bags, bought a ticket to Berlin, attended art classes, and the rest is history. A messy history, to put it mildly, one that includes two World Wars, the Russian Revolution, being flagged as “bourgeois” by the Communists and getting dismissed as “degenerate” by the Third Reich. Through daunting circumstances, Kandinsky persevered, longing for an art that would meld the natural world with the transcendental.

A nagging question remains: did Kandinsky achieve this synthesis? Is it true, in the artist’s estimation, that “the impact of the acute angle of a triangle on a circle is actually as overwhelming in effect as the finger of God touching the finger of Adam”? In giving body and form to spiritual yearning, Kandinsky was only partially reinventing the wheel. We don’t know much about our cave-dwelling forebears some 30,000 years ago, but it’s a good bet their paintings of bison, bears and lions were freighted with metaphysical import. And God touching the finger of Adam? Yeah, Michelangelo was wise to art “animated with a spiritual breath.” In jettisoning representation, Kandinsky freed himself to pursue higher modes of knowledge and feeling — or so he thought.

But representation benefits from recognizability and, with it, a readier sense of empathy. Can a clean arrangement of ideograms placed upon an encompassing field of buttery yellow — that would be “Decisive Rose” (1932) — deliver anywhere near the same gravitas as Gerard David’s “The Crucifixion” (c. 1495), a painting located a few blocks down Fifth Avenue at the Metropolitan Museum of Art? A cruciform bereft of symbolic portent and a recognizable context becomes one sign among others. “Decisive Rose” is a splendid picture, but convert the wicked or unruly it won’t.

Kandinsky’s ballast-free compositions suggest the otherworldly; his palette evinces an aesthetic informed by Russian icons and stained-glass windows. Shape, space, line and color, in and of themselves, can prompt a multitude of reactions. But does Kandinsky strike a chord because he taps into the divine or is it because the pictures are — how to put it, exactly — fun? Turns out, these world-changing abstractions are not a little whimsical and often downright goofy. From the early forays into fairytale imagery to the not altogether coherent improvisations of his middle period to the tightly plotted rebuses that ended his days, Kandinsky discovered a guilt-free reason to play. Much in the same way Piet Mondrian rooted himself in some dubious precincts of the occult so that he could boogie-woogie down Broadway, Kandinsky indulged airy-fairy theorizing in order to follow up on some promiscuous caprices. When the brush was put to canvas, in so many words, Madame Blavatsky was given the bum’s rush. Take note of the religious heavy breathing surrounding Around the Circle, but don’t let it obscure the way in which a troubled man who lived during troubled times discovered the means by which he could let his hair down. In the end, that may be the most spiritual pursuit of all.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2022 World edition.