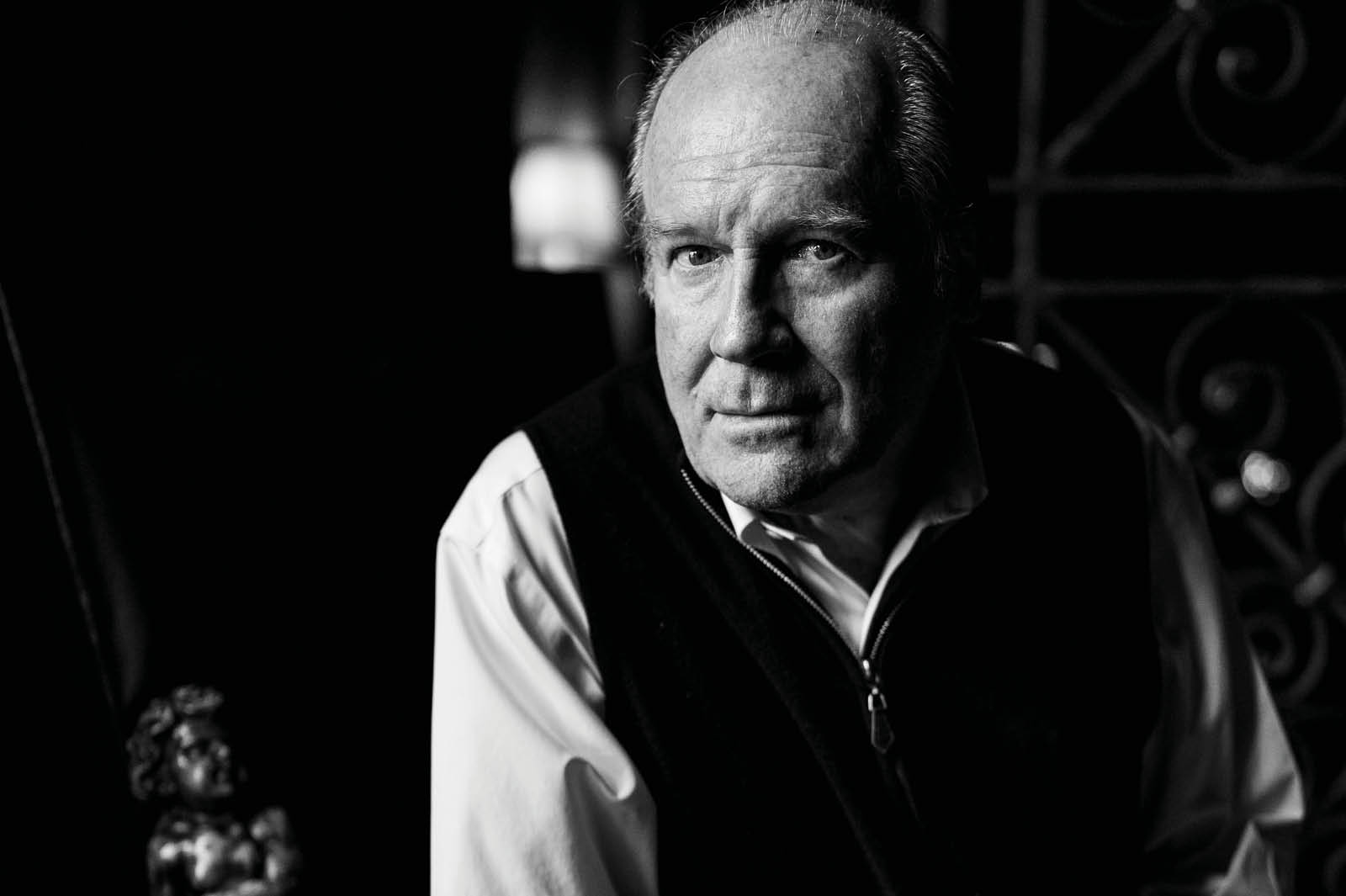

The Wolves of Eternity is the second volume in Karl Ove Knausgård’s trilogy which began with The Morning Star, but is that book’s prequel. The Morning Star examined events in the lives of various narrators at the time of the appearance of a bright new celestial body, bringing uncharacteristic heat and luminosity to Norway. It read like a shiver-inducing drama penned by a combination of Phil Redmond, Irvine Welsh and Stephen King. Part of its genius lay in fleshing out the characters by expressing the ugly thoughts we all keep repressed: irritation with over-familiar strangers; frustration with lovers; the thunderbolt of lust; and boundaries and the ways they are breached.

The Wolves of Eternity is written in the same immersive style, though the characters are different. It is so engrossing and entertaining that I crammed in its 800 pages like a glutton devouring a box of chocolates. The story revolves around a young man whose father had another life with a Russian woman, and his investigation of those secrets, but its themes overlap with those of The Morning Star: whether the complexity of life can wholly be explained by the Big Bang and evolution; whether death can be avoided; and the myriad forms of communication in eco-systems about which humans are ignorant.

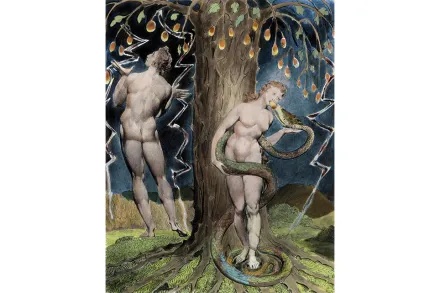

In literature, the morning star has been likened to both Jesus and the devil. The first book highlighted the strange phenomena that coincided with the appearance of the new star. In this prequel, the star is rising, and some of the characters experience sinister incidents which may or may not be related to this.

A Russian woman writes a treatise on attempts to avoid or reverse death. These include some horrifying experiments, and, ironically, one of the investigators dies in his quest for eternal life. Meanwhile, a friend of the woman tries to discover whether the forest as a whole has any sort of consciousness forged by communication between the trees and other elements.

Knausgård’s own life contributes much to his insights into people: his experience of an abusive father; the hungry obsession with love that parental withholding of love inspires; the uncompromising openness that is the legacy of those forced to suppress the truth in childhood; the heavy drinking. I was mesmerized throughout this book. The translation is also excellent, managing to maintain rhyme in translated poems, puns and songs, and incorporate faultless everyday argot. More, please.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.