John Giorno’s breakthrough work, he explains in his richly salacious telltale memoir of the Sixties New York art scene, was ‘Pornographic Poem’. In 1964, Giorno took phrases from mimeographed erotica and reconstituted them as homosexual lyric poetry: ‘I shivered/ looking up / at these erect pricks/ all different/ lengths/ and widths/ and knowing/ that each one/ was going up/ my ass hole.’

‘Pornographic Poem’ is a ‘readymade’ or ‘cut-up’ that follows Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and William S. Burroughs — all of them artistic appropriators, and all of them Giorno’s lovers. These revolutionary artists are Giorno’s ‘great demon kings’. Giorno feeds off their genius, but they feed off the young and beautiful Giorno for connections — to sex, drugs and the new youth culture. Warhol teases him as ‘just a big piece of meat’. Rauschenberg is ‘a poisonous snake’. Burroughs, Giorno’s greatest hero, is a ‘black hole’ and ‘bimbo sponge’.

Giorno has a great talent for connections. At the Bunker, his home on the Bowery, Giorno created one of the great New York salons. Other significant friends, collaborators and, frequently, sexual partners include the poet Allen Ginsberg, the composer John Cage, the novelists Paul and Jane Bowles, the surrealist technologist Brion Gysin, the sound innovator Bob Moog (inventor of the Moog synthesizer), and younger visual artists and poets such as Keith Haring and Anne Waldman.

In the Sixties, Giorno saw poetry as ‘75 years behind painting and sculpture and dance and music’. He spent his life making up for lost time. Giorno describes himself as ‘a poet who thought a poem could take many forms’, and he updated poetry by performing it in new media. In 1965 he created Giorno Poetry Systems, a non-profit collective and record label which transformed poetry into soundscapes by looping, delaying and intermixing reading voices.

Next, he orchestrated the Dial-a-Poem project: anyone with a telephone line could call the Lower East Side and listen to the Black Panther Bobby Seale or the poet Diane Di Prima read poetry about race riots and assembling a Molotov cocktail. On the first Giorno Poetry Systems album, from 1965, 12 different artists including Rauschenberg and the choreographers Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown read about ‘erect pricks’ 12 different ways, like a Warholian wall of repeated but unique silkscreens.

Giorno’s memoir is as explicit as his verse. We read of Warhol’s ‘little pink tongue’ licking his shoes, of Rauschenberg’s ‘soft, silken, voluptuous asshole’, and Giorno’s italicized surprise on seeing Burroughs’s ‘dick as small as a clitoris’. This is more than sensationalist gossip. Giorno deliberately challenged Pop artists when they edited gay desires out of their art. In the Sixties even Warhol, the most swish of the Pop superstars, reserved his explicitly homoerotic artwork for a small coterie in order to retain his appeal to a mass audience. He repeatedly rebuffed Giorno’s suggestion that he film two men kissing, ‘like Doris Day and Rock Hudson’. Warhol would slowly remove Giorno from his life.

***

A print and digital subscription to The Spectator is just $7.99 a month

***

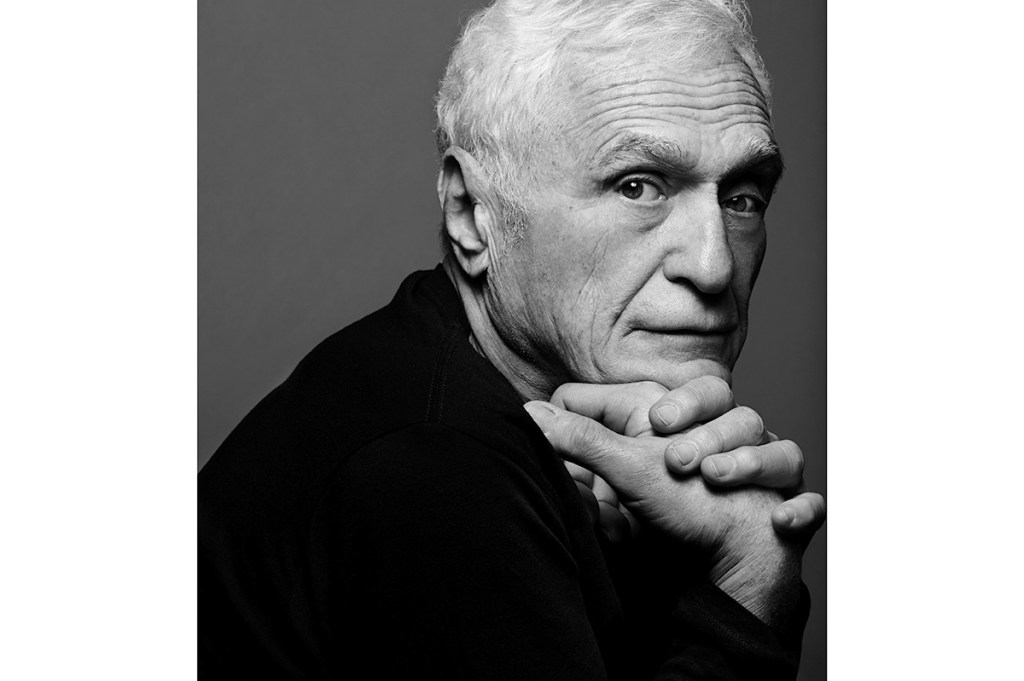

Giorno, who died at 82 a week after finishing this memoir in 2019, was a romantic who became entwined with the 20th century’s major ironists. He believed in the redemptive power of sex, art and expanded consciousness. None of his demon lovers believed in the liberation of the mind, body and spirit. ‘It is nothing more than the transference of power from one generation to another,’ said Jasper Johns coldly.

But Johns was right in many ways, and Giorno came to recognize it. Aids devastated Giorno’s romanticism: ‘It felt like the ultimate failure of all our aspiration of love, sexual freedom, and drugs. The heroic effort and accomplishment of the gay liberation movement, the sexual openness of equality, came to nothing.’ Giorno kept the faith not through nostalgia, but by creating new forms of expression. He transformed 222 Bowery and the Bunker into a Buddhist shrine and opened it to monks from around the world. Amid the Aids disaster of the 1980s, Giorno Poetry Systems gave grants to the sick. For Giorno this felt like ‘an extension of the golden age of promiscuity, when you made love to whomever you were mutually attracted to, even if they were strangers’.

Giorno’s ‘demon kings’ were demons in their ego-driven self-obsession, and kings because of their power to alter the way we understand art and our world. Their greatness, Giorno feared, came from the union of the two. He spent his life wrestling with this Faustian coupling. Great Demon Kings is an indispensably intimate account of the queer lives of Warhol, Rauschenberg, Johns and Burroughs. Even more significantly, Giorno’s memoir is haunted by the knowledge that great art requires a betrayal of the romantic vision of love, equality and the community of strangers.

This article is in The Spectator’s August 2020 US edition.