Paris

The Louvre’s Leonardo da Vinci is the latest Renaissance master in a procession of epic anniversary retrospectives — after 2017’s hugely popular Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, before next year’s inevitably popular marking of the cinquecentenary of the death of Raphael at the National Gallery in London. This year, with Leonardo’s posterity passing the same necroversary, the Louvre is augmenting its five Leonardo oils –– more than any other museum, thanks to the light fingers of legendary art critic Napoleon Bonaparte –– with a further six loans. This allows us to see 11 of the fewer than 20 oils that the experts attribute to Leonardo, with three of the Louvre’s holdings restored to gleaming life, as well as a mountain of sketches and an ancillary apparatus of x-rays. The result is a stunning journey into what Leonardo called the ‘science of painting’.

This exhibition affirms the modern image of Leonardo as a creative uomo universale who cracked the code of Nature: a kind of Einstein with a paintbrush. The familiar chronology of Leonardo’s story is here too: his bouncing between the courts of Italy in search of patrons and a quiet place to work during wartime, his last years in France. Last summer, I listened to Jordi Savall’s consort performing a sonic biography, an attempt to evoke Leonardo’s states of mind through the music of each city and court he lived in. This exhibition attains a similarly associative feel by weaving the chronology into a thematic approach that focusses our attention on inner processes of development.

Born at Vinci near Florence in 1452, Leonardo was apprenticed to Andrea del Verrocchio. It was from Verrocchio that Leonardo learnt to look for the sculptural in form and movement, and the dramatic techniques of chiaroscuro (modeling in light and dark) and sfumato (the ‘smoky’ effect). The exhibition’s first room shows Leonardo doing his homework, with sheet after sheet of drapery studies in which pencil looks like cloth and cloth like marble.

Leonardo soon moved to painting, with imported inspiration from Flemish portraitists and native inspiration from the relentless competition between workshops. By the late 1470s, he had assimilated his training into what he called componimento inculto, ‘intuitive composition’, in which rapid execution, the result of long study, follows the moving effects of form and light. The most effective demonstration of this method might be a giant ‘reflectogram’ of ‘The Adoration of the Magi’ (1481), a tumult of charcoal and brush with ideas reworked, superimposed and sometimes cast into darkness. This fluidity and complexity — not so much over-thinking his work as over-seeing it — seems to have contributed to Leonardo’s growing inability to finish his paintings. At least some of the frustration of ‘St Jerome Penitent’ (Vatican Galleries) seems to emanate from the unfinished nature of the painting, with the saint’s strained musculature exposed between bare ground and swathes of darkness.

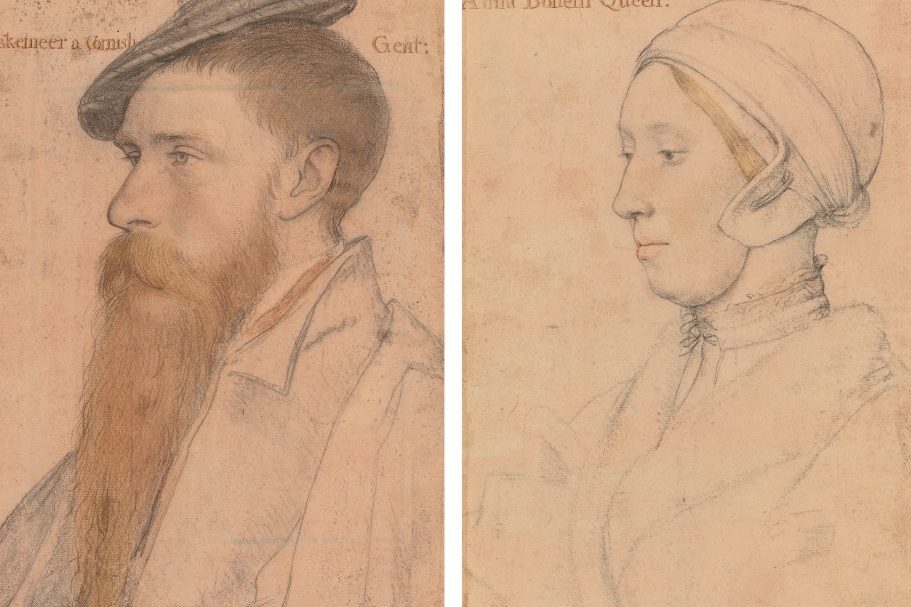

Moving to Milan, Leonardo turned entertainer, creating mottos, emblems, pageants and wedding parties for the court of Ludovico Sforza. The passage to the centerpiece of this phase, the Louvre’s dreamlike ‘Virgin of the Rocks’ (c. 1483-86), is lined with portraits by Leonardo (‘The Musician’ from Milan, ‘La Belle Ferronnière’ from the Louvre), and the sketches through which Leonardo refined the ‘Virgin of the Rocks’. If the portraits show the lifelike effect, the sketches, even the surging fury of the sketches for ‘The Battle of Anghiari’, ‘The Battle of Cascina’ and the mythological combats, reveal his consciousness of spectacle; Leonardo, for all his tumult and violence, is a cold-eyed, mathematical painter.

The next space is given to Leonardo the scientist, with the cases of notebooks and calculations dominated by Marco D’Oggiono’s copy of Leonardo’s ‘Last Supper’ mural (c. 1490s), and the show quietly stolen by Leonardo’s giant head sketches of half a dozen Apostles. Our elusive hero, having decamped from Milan after the French conquest of 1499, is now back in Florence. These were the years of ‘The Battle of Anghiari’ and ‘The Battle of Cascina’, the never-completed murals for the city’s new assembly hall, the mythological experiment of ‘Leda’ the ‘Mona Lisa’ (which remains behind its usual fortifications in the museum’s main galleries, but is encountered here in a virtual-reality antechamber).

Moving to France and onto the payroll of Francis I, Leonardo made the deeply affecting, and hence mercilessly contrived, ‘The Virgin and Child with St Anne’ (c. 1503). It is typical of this exhibition’s comprehensiveness that the closely related and gloriously complex charcoal cartoon, ‘The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John’ (c. 1499-1500 or 1506-1508), has traveled to Paris from London. The power of conception and execution, the searching out of realistic presence and effect, are devastating on this scale and in such quantity.

As for quality, the expensive and unconvincing ‘Salvator Mundi’ is tucked onto a side wall and attributed only to Leonardo’s studio. Completeness, always an ideal Leonardo struggled with, requires the presence of ‘Salvator Mundi’ here. The Louvre’s polite disavowal, and the placing of ‘Salvator Mundi’ among Leonardo oils of obviously higher quality, tells its own story. As does this exhibition, thematic digressions and all: a faultless and lavish example of the sort of show that requires holdings, resources and scholarship that few museums possess, and which the Louvre excels at mounting.