It’s 1960, and the clock has struck seven in the morning on Manhattan Island. A car weaves through the clamorous city as the morning sun settles. In the front seat are the Canadian-American painter Philip Guston and the British art critic David Sylvester; the pair have just enjoyed a sobering Chinese meal after a long night of drinking with Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, which called for the digestif of a drive. It has been an epochal night for Sylvester; he just doesn’t know it yet.

In 1996, Sylvester, who would have turned 100 this year, wrote his essay “Curriculum Vitae” later reproduced in his acclaimed About Modern Art: Critical Essays 1948-2000. In it, he reflected on this landmark evening: “It had, of course, been like the evening chez Kahnweiler in transforming my life.” This referred to the time in his early twenties when Sylvester rubbed shoulders in Paris with luminaries like Alberto Giacometti thanks to a coffee invitation from the collector Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. Sylvester was the master of being in the right place at the right time and with the right people.

In 1960, he capitalized on his newly forged connections with the New York School and conducted a number of interviews for the BBC from Fifth Avenue.

These interviews would come to define Sylvester as one of the twentieth-century art world’s most important transatlantic figures. He was a critic whose perceptive commentary was advantageously tied to the fact that he could call these artists friends and observe their behaviors not just on a broadcast but over late-night dim sum.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Lauded for an interview style that explored the artist’s process and intentions without the jargon-ridden “artspeak,” he was the first critic to receive a Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for an exhibition of Francis Bacon’s work — hence his later nickname as the “Golden Lion of English art writing.” He was also praised for organizing landmark twentieth-century exhibitions, for the Magritte catalogue raisonné (which took him over a quarter of a century) and for bringing the art of Bacon, Henry Moore and Lucian Freud to international recognition. His revealing interviews with Bacon, in particular — conducted over twenty-five years — are an invaluable insight into the mind of one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century.

Born in 1924 in North London, Anthony David Bernard Sylvester hailed from a family of Russian-Jewish silver dealers and fish merchants. He “attended” University College School (he was expelled for truancy) and was subsequently turfed out of his Orthodox Jewish home for contemplating Roman Catholicism. When he stumbled upon a black-and-white reproduction of Matisse’s La Danse, his “awareness of the music of form” was piqued. Prompted by an interviewer for Frieze in 1996 to speak about his lifelong fascination with art, he replied: “Art turns me on, that’s all.”

This erotically charged fascination led an eighteen-year-old Sylvester to his first job in the 1940s, as a critic for the socialist paper Tribune — the then-editor being Aneurin Bevan, supported by literary editor and columnist George Orwell. In 1947, he left for Paris and supported himself with reviewing jobs while frequenting the studios of art- ists like Giacometti and Fernand Léger. A year later, he gave broadcasts for the BBC, and by 1951, he had curated a retrospective exhibition of Henry Moore’s sculpture at the Tate Gallery.

In waving the British flag for figurative painting, Sylvester was quick to cast aspersions on American Abstract Expressionism. In 1950, he was commissioned by the US periodical the Nation to cover the Venice Biennale. As he snaked his way around the US Pavilion, he was left unimpressed by the works of Jackson Pollock and de Kooning, dismissing them as derivative of European abstract painting.

“If this pavilion is representative, American painting has fallen prey to a Germanic overestimation on the importance of self- expression,” he wrote with an acid pen, going on to say that the paintings “represent the seamier side of America — sentimentalism, hysteria and an undirected and undisciplined exuberance.”

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]The critic Clement Greenberg, who had recommended Sylvester to the Nation in the first place, was not best pleased. He dismissed Sylvester’s “European view of American art” as anti-American, concurring with the New York Times art critic Aline Louchheim’s opinion that the European responses to the US Pavilion revealed their habit of thinking of Americans as “cultural barbarians,” possibly exacerbated by the economic dependence that came with Marshall Plan aid.

It would be another six years until Sylvester had his Damascene conversion and “woke up to the value” of American Abstract Expressionism. Exhibitions spotlighting American artists were few and far between at this point. But when the Tate Gallery put on its 1956 exhibition Modern Art in the United States, Sylvester recognized he had acted in an “obtuse” fashion over American art, noting the exhibition’s ripples on the London art scene. He even responded to criticisms of the exhibition, writing:

Criticisms of the Tate’s American show suggest that people think Jackson Pollock is a brutal, messy painter. Such critics must have been reading so much about Pollock’s practice of dribbling paint out of holes in the bottoms of tins — which certainly sounds crude — that they haven’t left themselves time to look at Pollock’s paintings and to find out that, whatever they may be or not be, they’re about as crude as Fragonard’s.

In 1959, the touring MoMA show The New American Painting allowed British audiences to see works by de Kooning, Guston and Pollock for the first time. In a broadcast for the BBC, Sylvester said he began to appreciate American art, directly comparing it to British art at the Tate; he was awestruck by de Kooning’s 1957 February, praised Guston for his “extraordinary amount of passion” and Pollock for his “gestures which manage to have at one and the same time a sort of Dionysian abandon and yet never to lose control.” He extolled the exhibiting artists for “the rigor, seriousness, vitality and variety” with which they approached painting, even jabbing at the “stagnancy” of European art.

In 1960, he visited the US for the first time after receiving a State Department grant intended to bring “opinion leaders” to America in the hope they would report favorably on their experiences — there was no mention this time of “sentimentalism, hysteria and… undirected and undisciplined exuberance.”

Sylvester had decided to visit the studios of the Abstract Expressionists but recoiled at being introduced to these “high Bohemians” by government officials. The critic insisted on spending the first couple of days in New York, and it was here that his “miracle” occurred.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]He received an invitation to dinner with the American journalist Irving Kristol and later that evening, broke bread and drank wine with the likes of de Kooning and others. They progressed to the Cedar Bar, the New York School’s neighborhood watering hole, for a nightcap, and Sylvester was introduced to Kline and Guston. Au revoir to café with the Frenchies; it was time for whisky highballs with the Yanks.

After his 1960 interviews were broadcast on the BBC, Sylvester wrote of his time in New York under the headline “Success Story” in the New Statesman, examining the effects of their recent success on the Abstract Expressionists, noting their unpretentious attitude and their art that was not “lousy with class consciousness” — a not-so-subtle dig at the London art scene. For the New Statesman he wrote “A New Orthodoxy,” making a case for more exhibitions in Britain showcasing a range of American art.

In what feels like an act of atonement, back in Britain Sylvester became a proselytizer for American art in the latter part of the twentieth century. Pop Art and Minimalism were the heirs to Abstract Expressionism, and throughout the 1960s, he celebrated English and American pop artists who represented what he called “Coca-Cola culture”: “Most of English Pop Art is a dream, a wistful dream of far-off Californian glamour.”

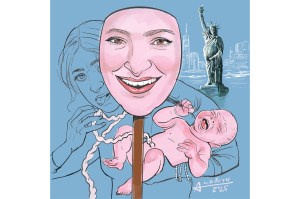

After that fortuitous night in 1960 and for the next forty years, Sylvester regularly interviewed British and American artists and critiqued their work, becoming a transatlantic interpreter for century-defining art. It feels somewhat cyclical that one of Sylvester’s daughters, the British-born, New York-based contemporary painter Cecily Brown, has made a name for herself producing works so heavily influenced by the expression and abstraction of de Kooning and Bacon.

Shortly before his death in 2001, Sylvester published Interviews with American Artists, a compilation threading together his encounters with the views, styles and techniques of everyone from de Kooning to Guston. It is a fitting swansong for a critic who dedicated his life’s work to making waves for artists on both sides of the Atlantic, leaving ripples that are still felt today.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2024 World edition.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]

Leave a Reply