Many movie actors are famous for their unmistakable voices — people like Sean Connery, John Wayne and Peter Lorre, who all pub comedians mimic. But how many directors are like that? Only one: the German auteur Werner Herzog, hero of the New German Cinema, who at the age of eighty-one has published this head-spinning, free-associating memoir. Its German title, Jeder Für Sich Und Gott Gegen Alle, was also the original, anarchic title of Herzog’s 1974 film The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, based on the true story of a boy reportedly brought up in an isolated darkened cell.

Herzog’s rasping, lilting, inscrutably sibilant and sinister voice, a vital part of all his documentaries and the various villains he’s played on screen for other directors, is described by him as having “the South German twang of my first language, Bavarian. And I accept too that I speak English with a strong accent, maybe not so strong as Henry Kissinger’s.”

He says that he developed this voice through an interest in hypnosis and it’s got him three different cameo-gigs on The Simpsons.

Herzog’s distinctive world view has always gravitated towards the heroism of the lone individual

You have to hear that extraordinary voice in your head while reading this book — as, for example, when he recalls how upset he was to interview a traumatized child soldier in Honduras while researching his 1984 movie Ballad of the Little Soldier: “His mother was chopped to pieces with a machete before his eyes… Christ on a bike.” A fellow film critic and I used to terrify each other with the thought of what it would be like to be shouted at by Arnold Schwarzenegger in his native German. What could be scarier? One thing: being shouted at by Werner Herzog in German.

Herzog is often facetiously called a mad genius, and yet maybe there is no other way of thinking about him, and this book underlines it. He really is a kind of genius, and perhaps there is an ecstatic madness in the way he has pursued his extraordinary career, at such a pitch, for so long, and mostly as an independent film-maker who has cultivated a very distinctive world view — always gravitating towards the magnificent heroism of the extreme, lone individual.

Film historians may gasp at the folies de grandeur of directors such as Francis Ford Coppola with his epic Apocalypse Now or Michael Cimino with Heaven’s Gate, a film whose excesses virtually crashed the entire American New Wave. But these people had studio backing. Herzog was independent when he made his greatest films, all alone and justified in feeling that God was against him. These were films like his extraordinary Aguirre, The Wrath of God in 1972, with Klaus Kinski as the crazed conquistador on an obsessive mission to find El Dorado in the Amazon; or his even crazier Fitzcarraldoin 1982, with Kinski (again) as the swivel-eyed nineteenth-century opera enthusiast and would-be rubber baron who mesmerizes the saucer-eyed indigenous peoples of Peru with opera played on his windup gramophone. In this way he terrifies them into slave labor, forcing them to drag a steamship across land and into a commercially advantageous part of the river. Which is what making his films must have felt like.

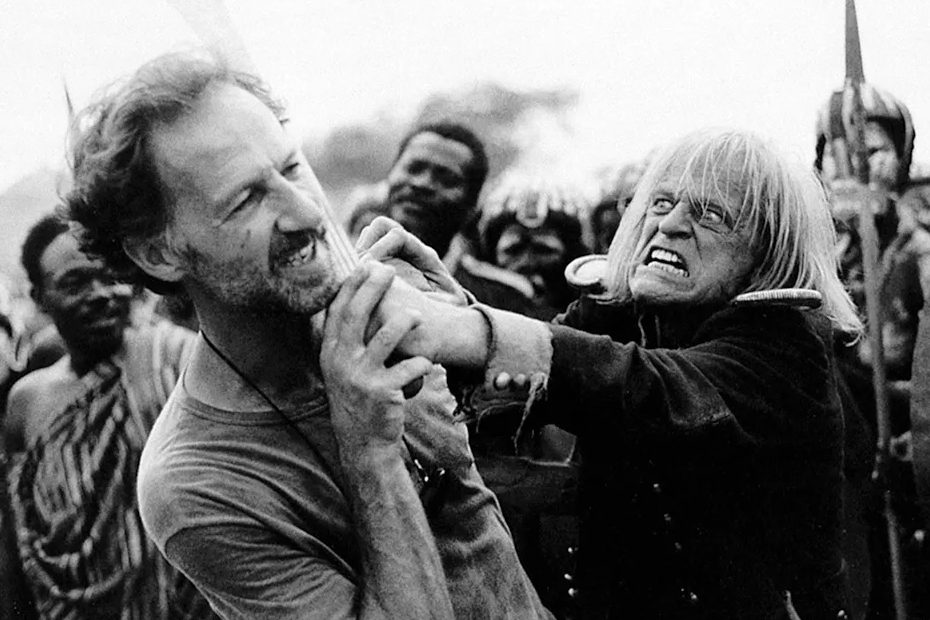

Herzog had to command an entire cast and crew as they endured appalling heat and discomfort in the jungles and rivers (with his loyal half-brother Lucki looking after the shaky finances). And of course he had to repeatedly confront his barking mad leading man Kinski, who at one point in the filming of Fitzcarraldo threatened him with a loaded revolver. Herzog couldn’t or wouldn’t make these films in the comfort of a studio, and in any case digital fakery was not available in those days. He endured the real agony and the real terror — and his natural monomaniac passion alchemized it into cinema.

But all this was done without romanticizing cinema or mythologizing it or even seeming to be very interested in it. A Fellini or Truffaut or Spielberg might swoon over memories of going to movie theatres in their boyhood: the seats, the darkness, the magic on screen, the posters in the foyer. Not Werner Herzog. He says he was utterly unaware of movies growing up — unaware of most modern technology in fact. He tells us he made his first telephone call at the age of seventeen. One chapter concludes with a ringing dismissal of psychoanalysis: “I’m convinced that it’s psychoanalysis — along with a few other mistakes — that has made the twentieth century so terrible. As far as I’m concerned, the twentieth century, in its entirety, was a mistake.”

The twentieth century a mistake? But wasn’t that the century that gave us the cinema? Fascinatingly, what seems to have sparked his interest in making films is noticing how the bad ones were made. He saw an action film in which two different people appeared to fall off a cliff and realized it was the same stunt shot from two different angles. You learn from bad films, he says. The good ones will keep you as uncritically rapt as a child.

His own childhood is wonderfully evoked — growing up in rural poverty during World War Two with his mother and brother in the Bavarian village of Sachrang, while his (detested) father was away serving with the Wehrmacht in France. The young Herzog was hot-tempered. Entirely deadpan, he describes having a knife fight with his brother over who got to own the family’s pet hamster. He also describes an encounter with an old woman: “There was also a witch who came for me, but my mother caught up to her and snatched me back, and from that time on I knew I wouldn’t wet my pants any more but get to the potty on time. On my right hand I had a mark where the witch had bitten me.”

All Herzog fans will see the delicious black comedy in these memories. Did they actually happen? Very possibly.

The book is a swirl of bizarre and unverifiable anecdotes — stories for which the author is perhaps not on oath, as they say, and they become more dizzying the further Herzog gets from the rooted reality of his childhood and early adulthood. There is a sojourn in Manchester, where he had a girlfriend, and in Munich where he briefly studied literature, and first met the highly-strung Kinski, before taking jobs to fund movies.

Entirely deadpan, he describes having a knife fight with his brother about who got to own the family’s hamster

And from there? Well, the movies themselves are Herzog’s biography: Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo, Heart of Glass, Nosferatu, Grizzly Man. His prose is a vehement rush of ideas, and notes for films as yet unmade, in which personal details are put in out of sequence — a clever way of preserving his privacy. There are also his opera productions, perhaps especially his plan for the opera house in Sciacca in Sicily, where he proposed to mount Wagner’s Götterdämmerung for one night only, removing the audience and cast from the building after the second act, dynamiting the entire place and then performing the rest in the smoking ruins. The outraged townsfolk and city authorities prevented him from doing it; but I have no doubt he would have, given a fraction of a chance.

There is also a black-comic laugh when Herzog describes his friendship with Bruce Chatwin, whose work he passionately admired. When Chatwin lay dying from Aids in 1989, Herzog visited him at his bedside and Chatwin asked him to “end his torment.” Herzog immediately replied unsentimentally: “Do you want me to brain you with a cricket bat or asphyxiate you with a pillow?” Evidently taken aback by these suggestions, Chatwin weakly suggested some fast-acting drugs. Herzog had none.

In the end, Herzog is an enigma, just like his mysterious savage innocent, Kaspar Hauser. He is an artist whose life story here is a dervish dance of details and anecdotes within which the real life is still kept secret.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply