Cheerleaders save the world. Vampires gain souls. Ellen Ripley comes back to life as a half-alien. In the case of Willow Rosenberg, Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s geeky, lesbian BFF, she’s a good witch one year, Southern California’s equivalent of the Wicked Witch of the West the next, and only a year later, the key to stopping an apocalypse. One season, you’re good; the next, you’re bad; then, finally, you’re the savior.

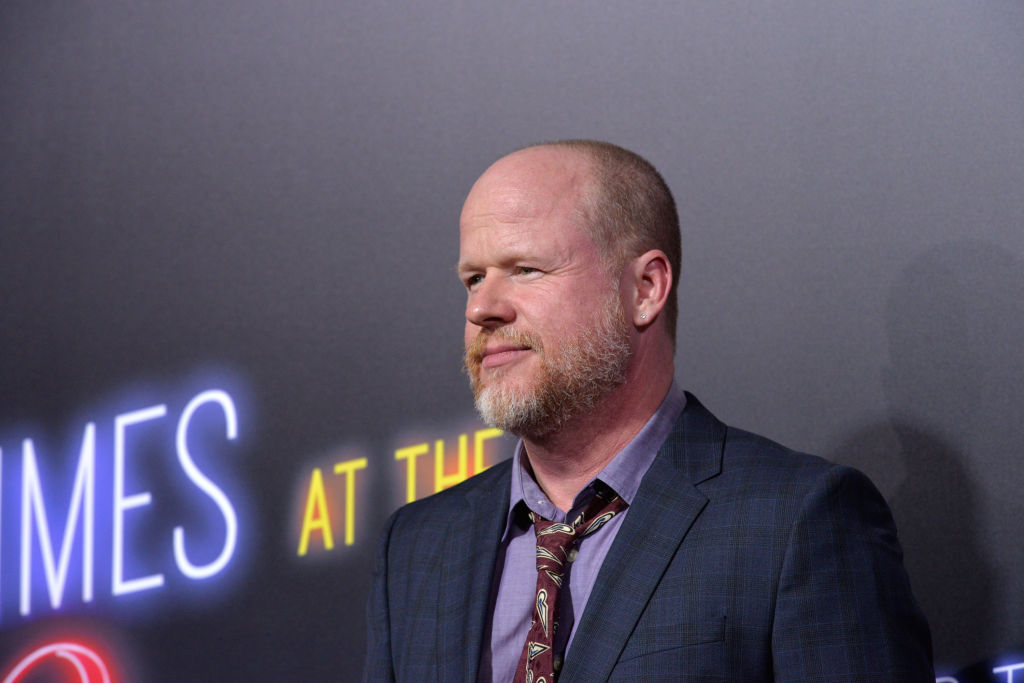

This is the world Joss Whedon envisions across six television shows (Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly, Dollhouse, Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. and The Nevers), dozens of comics (Buffy spin-offs, The Runaways and an acclaimed run on the Astonishing X-Men), and numerous films: Toy Story, Alien: Resurrection, Serenity, The Cabin in the Woods, Much Ado About Nothing, a bunch of uncredited rewrites of hits like Speed and, love it or hate it, the most influential blockbuster of this century, the movie that spawned dozens of superhero flicks: The Avengers. Whedon’s work varies from Disney cartoons to a supernatural teen soap opera to a Shakespeare adaptation, but across genres, he teaches audiences that a hero can become a villain, a villain can turn into a hero, and often, humans (or their vampire counterparts) are both good and bad.

So it was strange to see fans abandon the man-boy wonder when Whedon was accused of cheating on his wife with actors and verbally abusing his casts. The accusations were awful. Ray Fisher claimed Whedon altered his skin color in post-production for Justice League, and Charisma Carpenter alleged Whedon encouraged her to get an abortion when she got pregnant. When she refused, Whedon allegedly killed off her character, Cordelia, on Angel. Whedon acknowledged he’d slept with some of his actresses and was a dick, but denied Carpenter’s and Fisher’s specific allegations. He even half-apologized in a New York magazine profile.

Of course, no apology was ever enough for the nerd herd. “Off with his head,” his former fans declared. Their disavowal is tragic because Whedon not only created some of the most influential pop art of the past twenty-five years, but his work teaches nuance, which we could use more of in our polarized world.

Part of Whedon’s problems go back to his career-long public relations strategy. Whedon broke out in Hollywood as a script doctor, rewriting hits like Twister, then attempted to recreate his flop 1992 movie, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, as a TV show on the struggling WB network. The show departed from teen fluff in numerous ways: its premise inverted the horror trope of the dead teen girl, with Buffy slaying the vampires — as Whedon put it, a metaphor for “high school as a horror movie.” And, at least in public, a very feminist metaphor at that.

“The very first mission statement of the show… was the joy of female power,” Whedon said in a 2001 Metroactive Art interview. “Having it, using it, sharing it.”

Male feminism became a pillar of the Whedon brand. An Entertainment Weekly listicle cited “strong women” as the defining feature of Whedon’s work. The Atlantic described academic writing, known as “Buffy studies,” popping up about Buffy as “a progressive, feminist challenge to gender hierarchy.” Whedon welcomed the branding, even accepting a 2006 Equality Now award from Meryl Streep that New York magazine described as for “men on the front lines” of women’s rights.

“It all goes back to my mother,” Whedon said in his acceptance speech. “She really was an extraordinary, inspirational, tough, cool, sexy, funny woman, and that’s the kind of woman I’ve always surrounded myself with.”

Over and over again, Whedon repeated the line about his mother, and reporters latched onto it. To journalists, it was a soundbite, nothing more, but if you parse the words, it’s a little more complicated. What kind of man calls his mother “sexy?” What happens when a man finds a woman “funny” but “tough?”

A complicated one. If you ignore the headlines and look closely at his work, it’s clear Whedon always had more complicated (and interesting) relationships with heroines. In the introduction to his graphic novel, Frey, Whedon describes how he gravitated to Marvel Comics as a kid but struggled to find a girl character to “crush on”:

My best buddy and I used to fight, in our pathetic — I meant to say “rich” — fantasy lives over the affections of any girl who showed the slightest spirit. But it was deeply slim pickings. Until [the teenage X-Men character] Kitty Pryde. She was such a figure of both affection and identification.

Teen Whedon respected Pryde as a fighter, an X-(wo)man who fought in intergalactic wars and walked through walls. He was also sexually attracted to her.

Whedon writes his protagonists as both female fighters and sex objects. Buffy kills vampires while wearing Sandy-at-the-end-of-Grease-level tight leather pants. In between slaying (and working with) monsters, bad-girl slayer Faith grinds with Buffy on a dancefloor. Although Whedon revolutionized TV with his complicated gay characters (Buffy’s Willow, Tara, Andrew, etc.), Buffy and Faith hump each other like girl-on-girl porn stars, not actual lesbians. His space opera, Firefly, focused just as much on girl fighters as girl sex workers; its crew of misfit rebels featured both second-in-command female captain Zoe and the space madam/hooker Inara. After Whedon took over the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Phase Two, Black Widow wore leather and wrapped her legs around her opponents’ necks so many times that the martial arts move inspired angry feminist blog posts.

Since his unraveling, Whedon has been accused of hypocrisy, but from the get-go, his TV shows acknowledged the downside of male sexuality. After the vampire Angel takes Buffy’s virginity in the series’ second season, Angel literally loses his soul. Near Buffy’s conclusion, the vampire Spike attempts to rape Buffy. Devastated that he hurt her, he then goes on a mission to regain his soul. When he returns to California, Buffy falls in love with him. Her friends reject the coupling, but Buffy, like Whedon, acknowledges the contradictions of sexuality, whether it’s love/hate relationships, the thrills of BDSM or the post-nut clarity of realizing your politically incorrect sexuality.

Post-cancellation, writers described Whedon’s work as traditionally liberal, but his politics were always much more complicated and interesting. Firefly follows rebels who have lost a galactic civil war. Although Dollhouse starts as a traditional critique of corporate America, it evolves into a much more complicated political world where corporate executives, a former FBI agent and slaves collaborate to take down a large corporation. Whedon mistrusts large central authorities. (And who can blame him? He worked in Hollywood!)

Whedon, of course, didn’t invent these themes — they’re tales older than one of Whedon’s favorites, Shakespeare — but he revolutionized how these stories unfolded on television. Each season Buffy squared off against a singular big bad, a departure from episodic mystery-of-the-week programming. Buffy was telling season-long serialized stories two years before David Chase’s The Sopranos premiered on HBO.

Whedon’s work was, as television critic Emily Nussbaum wrote in an influential essay, “equally [as] ambitious” as The Sopranos, but he told these stories within the teen soap opera genre. While HBO programmed New York Times readers to devour Dickensian stories on TV, Whedon reprogrammed the masses.

Today, it seems obvious that Whedon was taking the Marvel style of telling long arcs, such as The Dark Phoenix Saga, over the course of multiple issues, but in the Nineties and early 2000s, Hollywood still viewed comic book storytelling as risky. Whedon cemented this storytelling as the dominant mode with his 2012 film The Avengers, the first blockbuster superhero meet-up movie.

Everyone knows what came after — the abysmal DC movies, Netflix trying to create a Millarworld franchise — but what often goes amiss is that Whedon treated The Avengers as a dysfunctional family. “[The Avengers] should not even be in the same room, let alone on the same team. And that, to me, is the very definition of family,” Whedon said in a 2014 interview. It’s a vision similar to Buffy’s disparate “Scooby gang,” Firefly’s rebels, or even Toy Story’s odd couple, Woody and Buzz Lightyear.

Yet, since his downfall, his fans have refused to put two and two together. Whedon created a dysfunctional family on his sets, and he himself came from a twisted family. “There wasn’t a grown-up who didn’t have a drink in their hand by mid-afternoon,” he told New York magazine of his family. Those dysfunctions continued into his professional life. He broke into Hollywood writing on the notoriously volatile Roseanne set, which he described in Entertainment Weekly in 1997 as “baptism by radioactive waste.” “[Roseanne] was like two people,” he said in the same interview. “One was perfectly intelligent and good to be around. One was very cranky. You never knew which would show up.”

Joss Whedon is now very much canceled; there are no forthcoming projects that bear his name, and if he is still being used by Hollywood producers for script doctoring, it is very much on the quiet. Justice has been done. Except, of course, it hasn’t. Even post-cancellation, we still live in the pop culture universe Whedon created, even if his acolytes have failed to produce work to compare to their former idol’s. Whatever happens, we are worse off with a figure of Whedon’s imagination and verve banished from Hollywood.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply