Diplomatic negotiations are rarely fully described by their participants in books, for two reasons. They are usually secret until much later, and their intricacies can be boring. Politicians often include brief accounts in their memoirs, but these seldom reveal much about the process as a whole because, as I discovered by interviewing scores of them for my biography of Margaret Thatcher, they cannot avoid focusing almost exclusively on what they did and said (or think they did and said).

This book, however, overcomes the secrecy rule, because it is published nearly 40 years after the events described; and it overcomes the boredom problem because of the literary skill and intellectual grasp of its author. It is clear, precise, readable, sometimes drily funny.

The late Sir David Goodall, a Foreign Office man, held high rank in the Cabinet Office for most of the period when the Anglo-Irish Agreement (AIA) of 1985 was conceived, written and performed. Indeed, though he modestly does not say so, it might not have happened if he and the then cabinet secretary, Sir Robert Armstrong, had not been in their posts. It was Goodall, in a walk along the Grand Canal in Dublin, who first received (from his opposite number Michael Lillis) the Irish government’s ideas.

Goodall kindly showed me his memoir to help my biography. This book edits, comments on and publishes his account in full for the first time. The editor, the publisher and almost all the contributors are Irish, a fact which emphasizes the direction of the negotiations.

As the author saw it, the purpose was ‘according the Irish [by which he means the government of the Republic] some form of political involvement in Northern Ireland in return for a formal Irish recognition of the Union’. The most important person who wanted this was the Irish prime minister from 1982, Garret FitzGerald, a man with no visceral anti-Britishness and a great deal of donnish charm.

The most important person who did not much like this ‘basic equation’ was Mrs Thatcher. She most sincerely wanted peace in Northern Ireland, but she lacked sympathy for Irish nationalism, and did not believe the Republic had the right to get constitutionally involved, especially as it never fully delivered its oft-promised action against IRA terrorists hiding in the south. Despite some cheap shots aimed at FitzGerald in her memoirs, however, she did like and respect him, but she found his stream of fast, soft-spoken speech so hard to hear that he tired her out.

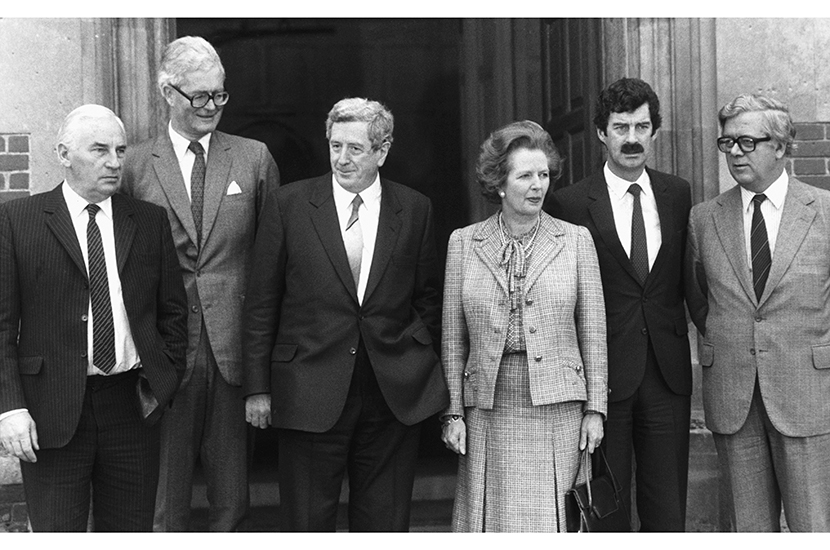

In formal terms, the negotiations were between the governments in London and Dublin, but in reality the two sides were Margaret Thatcher (with a little help from the Northern Ireland Office) vs everyone else — notably Fitzgerald and political colleagues; the foreign secretary, Geoffrey Howe; Armstrong and his Irish counterpart, Desmond Nally; Goodall and Lillis. The latter grouping kept asking one another versions of Howe’s question: ‘Are we winning?’ Howe did not mean ‘Are we winning for Britain?’ but ‘Are we winning against her?’

‘I was always thinking about Ireland,’ Goodall told me — a surprising thing for a British civil servant to say. Northern Ireland, that place apart, featured oddly little in Goodall’s thinking. Indeed, when he became involved in the process which led to the agreement, he had never been there. Although a shrewd observer, and sometimes even admirer of her methods, he was often upset by Thatcher’s approach. Her outbursts, he noted, were the authentic echo of ‘British ignorance, arrogance, contempt and dislike for Ireland down the ages’.

On the whole, Goodall’s side was winning. Thatcher was not well placed to shape the process. She had views about Northern Ireland, but no coherent alternative to propose. She was a Unionist, but she was unimpressed by Ulster’s Unionists. She might be prime minister but, on this subject, she had hardly any useful allies. Republican terrorists had murdered her best adviser, Airey Neave, in 1979.

The AIA was a true success in one very important respect: it firmly, for the first time, established trust between London and Dublin and thus a common purpose about the need for peace in the north. This proved foundational for the process which led to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. For this, the subtlety and goodwill of Armstrong and Goodall deserve high praise. Even today, with all the tensions over Brexit, Dublin communicates much more sensibly with London than does Brussels.

In another respect, however, the AIA failed, and was bound to do so. This was because the process had excluded the Unionists, whereas John Hume’s nationalist SDLP had been briefed throughout. The majority in the community were accorded fewer rights than the minority. So the deal could not ‘take’. It was diplomatic, not democratic.

This is part of the reason why Good Friday 1998 has not produced resurrection in Northern Ireland. It cleverly divided the spoils, but it did not bury the hatchet.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.