On a cold day at Disneyland, I walk through sugarplum-scented air, past a midcentury-modern poster for Alice in Wonderland, and beneath a plaque that reads, “Here you leave today and enter the world of yesterday, tomorrow and fantasy.” Walt Disney — the controversial impresario of twentieth-century animation and escapism, not the corporation that bears his name — intended his magic kingdom as an escape, a real-life never-never land devoid of the politics and troubles of the everyday.

But on this visit to the park, I encounter the here and now around every corner. Passersby notice that an empowered female pirate has replaced the bride-auction scene in the Pirates of the Caribbean ride. (“Did anyone really believe pirates were role models?” one visitor asks.) Dads complain about inflation hitting the prices of stuffed animals. On my phone, I read about how Florida governor Ron DeSantis signed legislation to strip Disneyland’s Florida-based sister park of its special tax status because (now former) Disney CEO Bob Chapek opposed the state’s Parental Rights in Education Act (or as Twitter calls it, the #DontSayGay bill).

The Walt Disney Company has for years now flailed against the onslaughts of the endless, boring culture wars. It’s responded in a myriad of ways but one of the strangest is by erasing bits and pieces of its own history in a curiously jerky, ad hoc fashion. Although Disney+ hosts the vile Peter Pan, whose racist song “What Made the Red Man Red?” makes Dances with Wolves seem woke, the site refuses to stream the obscure 1946 animated film Make Mine Music. The film includes inappropriate gunfire and Nelson Eddy singing the minstrel song “Shortnin’ Bread,” but it’s far less violent than The Mandalorian and way less racist than Dumbo’s crows. And by deplatforming Make Mine Music, Disney is hiding some of the finest work of one of old Hollywood’s most influential female artists: Mary Blair.

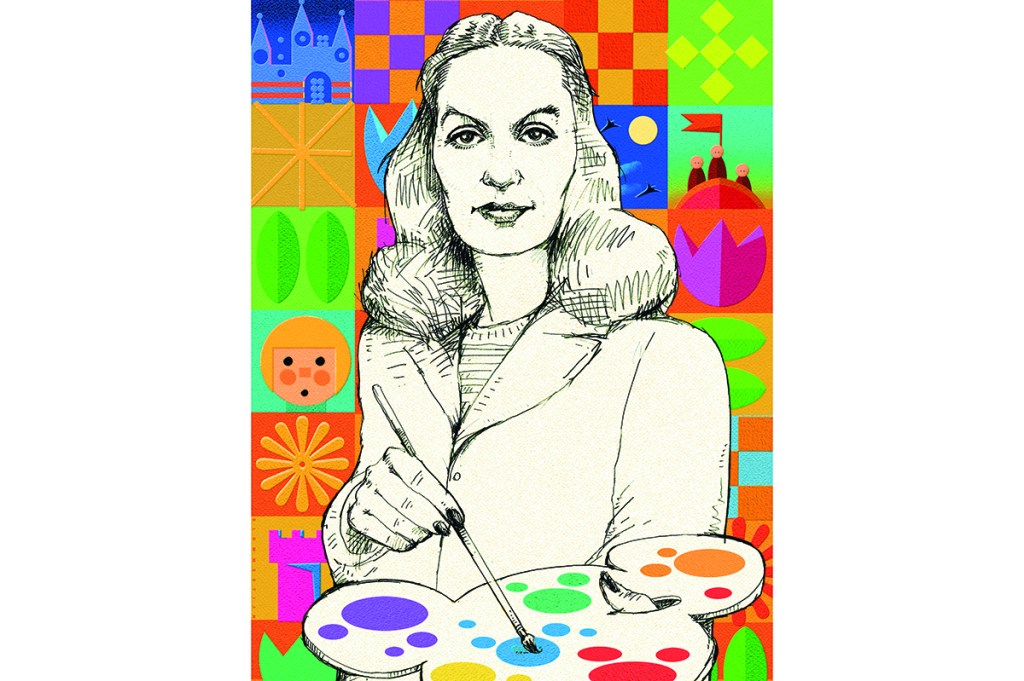

If you don’t know Blair’s name, you know her work. She worked behind the scenes as a conceptual artist at the Disney Studios intermittently from 1940 to Walt’s death in 1966, establishing the color schemes, shapes and style that defined Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan and other classic films that inspired everyone from anime legend Hayao Miyazaki to Pixar’s top directors. As Pixar executive Pete Docter told Blair’s niece, Jeanne Chamberlain, “At Pixar, if we’re stumped about something, we say, ‘Well, what would Mary do?’” Don’t believe him? Just look at Sally Carrera from 2006’s Cars, who looks nearly identical to Blair’s design for the living, breathing vehicle in 1952’s Susie the Little Blue Coupe, or the flat, 2-D opening credits for 2001’s Monsters, Inc., which resemble Blair’s concept drawings for both Make Mine Music and the Donald Duck vehicle The Three Caballeros.

As Nathalia Holt writes in The Queens of Animation, her study of the women who worked at Disney Studios, it’s easy to see how Blair’s bright, curvy modernist take on the caballeros’ trip south of the border earned her the nickname “Marijuana Blair.” But to stand before a Blair without knowing her life story is like visiting The Starry Night without knowing Van Gogh cut off his ear. To truly grasp Blair’s subtle emotional brilliance, you have to reckon with her painful life story — a tale too complicated, and far too interesting, for the bland streaming era.

Blair was born in 1911 to impoverished parents in McAlester, Oklahoma. As Blair was ahead of her time, her family’s poverty was ahead of the Great Depression’s. They bounced around. According to Oscar-winning animation historian John Canemaker’s Magic, Color, Flair: The World of Mary Blair, her father eventually landed a job at the Friendly Inn in Morgan Hill, California, and the family moved into a tiny third-floor apartment in the tiny hotel. From the difficult circumstances, Blair developed a quiet personality. “It was just a matter of growing up shy,” says her niece, Maggie Richardson, when I spoke to her in 2017. “They didn’t have a lot of money.”

Blair’s personality came out through her childhood drawings. Her parents bought her pencils, paints and drawing pads at a young age. Later, they encouraged her to attend the Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts) in Westlake. Blair’s early paintings contrast dramatically with her colorful Disney work, as does their subject matter. In her 1930s painting Okie Camp, she uses watercolors, the happiest of mediums, to starkly illustrate the situation of Dust Bowl migrants: a dirty gray tent against a brown train against a pouty blue sky. It’s a melancholy beginning for one of the women behind the happiest place on earth.

In 1934, Blair married a fellow Chouinard grad, Lee Blair. They tried to make it as artists, but even everyday folk weren’t making it during the Great Depression. So Lee turned to one of the few places where people were making an income during the financial calamity: Walt Disney Studios. He worked a variety of art jobs. Eventually, Mary found work at the Harman-Ising animation studio, where according to Holt, Joseph Barbera (later of Hanna-Barbera fame) would routinely wrap his arms around Blair and sexually harass her. Sick of the abuse, Blair begged Lee to find her work at Disney, and he did. “Disney was just a job for Blair. Mary went along for [Lee]s ride,” said Michael Labrie, former director of collections at the Walt Disney Family Museum, told me during a tour of the archives. Or, as Blair described the Thirties in Canemaker’s book, “All my peers thought I was prostituting my art… But I had to make a living.”

The Disney Studios both fit and defied every stereotype of Hollywood studios. Walt put a few women, like animator Retta Scott, in influential positions, and his films focused often on female characters — even compared to the corporation’s Princess explosion of the 1990s. According to Holt, women speak nearly half the dialogue in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Cinderella (1950) and Sleeping Beauty (1959), compared to 29 percent in 1991’s Beauty and the Beast and 10 percent in 1994’s The Lion King. The 2008 documentary Walt & El Grupo shows Blair dancing with men from the studio, having a ball. But Disney was far from a sorority. Blair could count her female work friends — Scott, Walt’s nurse Hazel George and costume designer Alice Davis — on one hand, and, Holt writes, “She sometimes felt she didn’t belong there.” The Disney studio was sexist, but still more nuanced than a simplistic assumption would have it.

In this complicated world, Blair found her artistic voice. In 1941, she accompanied Walt and his favorite artists, including Lee, on the South American trip recorded in the El Grupo documentary. Mary joined the trip as Lee’s wife and left as Walt’s favorite painter. Taking in the region’s mountains, colorful clothing, and smiling children, Blair painted flat, round faces on children wrapped in orange, red, pink and even-brighter pink smocks; the children hold candles up to a Disney-blue, wish-upon-a-star sky. The flat circles are laid on each other, at once appearing both one- and three-dimensional.

On a small piece of celluloid, Blair established as much depth as Caravaggio and as much abstraction as Picasso. Even more affectingly, Blair’s lines form children’s smiles that appear both earnest and melancholy. The children are both enjoying life and aware of the sadness that inevitably ruins childhood — the underlying theme we often forget hides in most classic Disney films. It’s a tragic modernist painting a world away from Blair’s dusty Grapes of Wrath watercolors.

“The trip completely altered the course of her artistic life,” Holt writes. “She found her palette while traveling, creating shades and contrasting colors that would forever become part of her identity and her art.”

It would also become a trademark of the Disney visual style and a part of innumerable childhoods. Sitting upright at her wooden easel, her long black nails wrapped around a brush, Blair applied watercolors, acrylics and pastels to tiny square pieces of paper, layering shape over shape, applying pinks next to reds and blues over blues, breaking every rule of the color wheel, and creating a midcentury-modern take on European fairy tales: a blue-cloaked woman turns a pumpkin into a carriage for a Cinderella clothed in pink rags; a faceless Alice in a blue dress peers through a maze of pink and purple in Wonderland; a sad but confrontational blonde pinup — Tinkerbell — pouts on a leaf that matches her slutty green dress — the list goes on and on. They were bright, they were colorful, but a dash of melancholy colored the splotches of pink and purple — and Walt loved them. According to Holt, he hung Blairs in his house and shouted at his male animators, “More Mary!”

The male animators envied Blair for winning Walt’s approval. Although they followed Blair’s colors and shapes, they refused to render her full modernism on the screen. But as long as Walt ruled the castle, Blair would be a star. When Lee found work in New York, Walt allowed Mary to work from her wooden home on Long Island, a country away from the Burbank studio. There she freelanced as well, illustrating everything from early Little Golden Books to Pall Mall cigarette ads, firmly establishing her niche in midcentury illustration.

Even in the grown-up tobacco ads, Blair exhibits a sense of both childlike whimsy and danger, with a lit cigarette resting against a curvy, bright red and green watermelon. The contradiction mirrored Blair’s personal life. During the day, Blair loved playing with her two sons, Donovan and Kevin, and two nieces. “She loved children,” says her niece Chamberlain. “She really did enjoy being with kids,” adds Richardson, who recites from memory to me over the phone: “I wish I could just take one more ride on the Ferris wheel with you… We’re looking forward to having Margaret with us.”

But on weekends and at night, Blair turned to the adult darkness. She loved to bet on horses at the racetrack and host cocktail parties, mixing Manhattans and martinis.

The parties seemed fun, but as in a fairy tale, villains lay in the shadow. At one party, Chamberlain says, Mary asked Lee’s friend, “Would you like to see my art?” When she led him into her studio, he stared at her watercolors. “He was floored that this was all with her, and he had no idea,” Chamberlain says. “He didn’t know, even at that time, that Mary was really the famous one, because Lee didn’t tell anybody… Lee had a big ego.”

Queens of Animation puts it more bluntly: Lee resented Mary. He drank to oblivion and shouted “cruel barbs” at her. He picked up a chair and hurled it at Mary, drawing blood. As their son Donovan aged, he showed symptoms of schizophrenia. One day, Chamberlain says, he ran down the street naked, wearing only a purple cape, his tragic symptoms bright and dark just like his mother’s art.

To cope, Mary turned to drinking. Eventually, she resigned from the Disney Studios, but she never left Walt’s imagination. Before his death, he lured her back one final time with one of her great loves — children. The year was 1964, and Bank of America and UNICEF were sponsoring a Disney ride for the New York World’s Fair. Walt, Richardson says, envisioned “a little boat ride” with children. He knew Mary was the one to bring his vision to life. In California, she collaborated with Imagineers and costume designer Alice Davis, painting concept designs of white, blue, pink, purple, red, yellow squares, triangles, piled on top of each other in small flat paintings. She then brought her concepts to life, making project decisions for the first time without running the gauntlet of bureaucratic approval.

Without the obstruction of stubborn, sexist men, she was able to paint the walls and dress the characters as she saw fit. When Walt came to the studio to see a dress rehearsal, Holt writes, he sat in a boat that employees pushed along the dry studio floor. A song began blasting out of the speakers: “It’s a small world after all / it’s a small world after all / it’s a small, small world.” It was Blair’s masterpiece — as Richardson calls it, an installation piece on wheels.

Walt had grand plans for Mary to do more, but he died very soon after his cancer diagnosis in 1966. The sexist studio men got their revenge on Blair, canceling her further projects. She entered a depression, drinking more and dying of a brain aneurysm in 1978 at age sixty-six — just about a decade before Miyazaki would begin deploying her palette on screen in Japan.

Today you’ll find little sign of the men who smeared Mary. Instead, when I visit Disneyland nearly sixty years later, the Blair masterpiece is on display. The line to enter wraps around a white and silver building, and when I sit in the teal boat and float past welcome signs in multiple languages, I burst into tears. Everyone around me is smiling — even the dolls are smiling! — but I cry because I know why the dolls look slightly melancholy, why some would find them creepy. Reflected in those smiling dolls is everything Blair went through. Blair herself is on display when we float into France, where a figure on the Eiffel Tower offers a shout-out to her blonde hair and flowered dress. I’m the only one on the boat who knows the reference.

It’s appropriate Blair is in France, because she was a true outsider. She was an outsider to her artist friends because she worked in Hollywood. She was an outsider to Hollywood because she was a real artist. She was an outsider to animation artists because she was a woman. And she was an outsider to women because Walt Disney respected her. She created real art — real popular art — but nobody would know that the woman on the Eiffel Tower was this genius, in this bland, safe, streaming age, because Hollywood is erasing its history. To preserve an outsider artist like Mary Blair, and understand what inspired her, you have to preserve the messy reality of life. Otherwise, you’re left with smiling dolls that don’t mean anything at all.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.